By Bernd Pulch | February 12, 2026 | Category: Media Control

In the autumn of 2024, Gallup released a survey that sent shockwaves through the American media establishment. Only 31 percent of Americans expressed a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the mass media—the lowest figure in the polling organization’s history, which stretches back to 1972. The record had been broken once before, in 2016, when confidence fell to 32 percent. Now it had fallen again, and the implications for democratic governance, public discourse, and the future of journalism were profound.

But the numbers tell only part of the story. Behind the statistics lies a more troubling phenomenon: not just declining trust in particular news outlets, but a fundamental crisis of confidence in the very concept of objective reporting. A growing proportion of the public no longer believes that accurate, unbiased news is even possible. They view all reporting as inherently political, all journalists as agents of particular agendas, and all news organizations as fronts for ideological campaigns masquerading as objective coverage.

This crisis did not emerge overnight. It is the product of decades of social, technological, and political change that have transformed the relationship between news media and the public. Understanding how we arrived at this point—and what might be done about it—is essential for anyone concerned about the future of democratic discourse.

The Numbers: A Half-Century of Decline

When Gallup first began asking Americans about their confidence in the media, the results would have been almost unrecognizable to contemporary audiences. In the early 1970s, more than two-thirds of Americans expressed confidence in newspapers, magazines, television, and radio to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly. This trust was not without foundation. The Watergate investigation, the Vietnam War coverage, and the emerging environmental movement had all demonstrated the power of investigative journalism to hold powerful institutions accountable.

But this golden age of media trust was already showing signs of erosion. The rise of cable television and the fragmentation of news sources began to erode the shared informational foundation on which democratic deliberation depends. As Americans gained access to more news outlets, they also gained access to more perspectives—and with those perspectives came the recognition that different outlets could present the same events in dramatically different ways.

The 1980s saw the emergence of a new form of media criticism that would prove transformative. Rush Limbaugh, whose nationally syndicated talk radio show launched in 1988, pioneered a particular brand of media criticism that castigated the national press as lapdogs for the Democratic establishment while presenting his own voice as an unvarnished and trustworthy source for conservative listeners. Through his acidic commentary and relentless attacks on media bias, Limbaugh planted seeds that would decades later bear bitter fruit.

The 1990s accelerated these trends. The emergence of the World Wide Web created new avenues for alternative media and new opportunities for criticism of mainstream outlets. Political polarization, which had declined in the post-World War II era, began to rise again, and with it came increasingly partisan interpretations of media coverage. The Clinton administration’s confrontations with the press, including aggressive responses to investigative reporting and efforts to manage news cycles, demonstrated how political actors could weaponize media criticism for partisan advantage.

The 2000s brought the internet revolution and the collapse of traditional business models that had supported serious journalism. As advertising revenue migrated to digital platforms, newspapers and magazines faced financial crisis. Newsroom staffing declined dramatically, and the depth of investigative reporting suffered accordingly. The 2008 financial crisis accelerated these trends, as media companies that had borrowed heavily against future advertising revenues found themselves on the brink of collapse.

By the time of the 2016 election, the stage was set for a dramatic shift in public attitudes toward the press. The combination of decades of partisan media criticism, the financial collapse of traditional journalism, and a political movement that made hostility to mainstream media a core tenet had created conditions in which a candidate who declared the press “the enemy of the American people” could gain traction with a substantial portion of the electorate.

The Three Drivers of Media Mistrust

Understanding the contemporary crisis of media trust requires examining three distinct but interconnected trends that have shaped the informational landscape: political polarization, platform proliferation, and economic disruption. Each has contributed to the current situation, and each must be addressed if media trust is to be restored.

Political polarization is perhaps the most obvious factor, and certainly the most discussed. As Americans have sorted themselves into increasingly distinct political tribes, their consumption of news has become more tribal as well. Republicans and Democrats now live in largely separate informational universes, with different sources of news, different interpretations of events, and different assessments of which outlets can be trusted.

This polarization has created what scholars call “hostile media effects,” in which partisans on both sides perceive coverage as biased against their side, even when independent assessments find coverage to be relatively balanced. Conservatives point to what they perceive as the liberal bias of elite outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post. Liberals point to the conservative tilt of Fox News and talk radio. Both sides have evidence for their positions, and both sides are, in a sense, correct: the media landscape does contain outlets that favor their respective viewpoints.

But the effect of this polarization extends beyond simple bias perception. When people believe that all media is biased, they lose motivation to seek out accurate information. If The New York Times is just as biased as Fox News, and both are just as biased as the latest blog post, then why bother distinguishing between them? This relativistic mindset undermines the very concept of factual reporting and creates openings for misinformation and propaganda.

The second driver is the proliferation of digital platforms that have transformed how Americans consume news. In the early 2000s, most Americans got their news from a handful of sources: the major broadcast networks, their local newspaper, and perhaps a few magazines. Today, the average American encounters news from dozens of sources every day, ranging from legacy newspapers to viral social media posts to podcasts to newsletters.

This proliferation has profound implications for trust. When people encounter contradictory claims from different sources, they must decide which to believe. The traditional solution—relying on the expertise and editorial standards of established news organizations—no longer seems adequate when those organizations are seen as just one opinion among many. Instead, many Americans have adopted a strategy of trusting only sources that confirm their existing beliefs, or abandoning the search for accurate information altogether.

Platform algorithms amplify this dynamic by prioritizing engagement over accuracy. Content that provokes strong emotional reactions—whether anger, fear, or satisfaction—receives more views and shares than content that provides nuanced analysis. This creates incentives for outlets to produce emotionally provocative content, which in turn trains audiences to expect and demand such content. The result is a news environment optimized for outrage rather than information.

The third driver is the economic disruption of the news industry. Over the past two decades, advertising revenue has migrated from traditional news outlets to digital platforms like Google and Facebook. Between 2000 and 2020, newspaper advertising revenue declined by more than 70 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars. Magazine and broadcast advertising followed similar trajectories, though less dramatically.

This financial collapse has had profound effects on the quality and quantity of news reporting. Newsroom employment, which peaked in the early 2000s at around 55,000 journalists at daily newspapers alone, has fallen to approximately 30,000. The remaining journalists are asked to produce more content with fewer resources, reducing the time available for investigative work and fact-checking. The closure of foreign bureaus and the reduction of coverage of state and local government have created “news deserts” where residents have little access to information about their own communities.

The economic crisis has also created perverse incentives that undermine public trust. As news outlets have become increasingly dependent on social media for traffic, they have focused on producing content optimized for sharing rather than accuracy. The pressure to generate viral content encourages sensationalism and discourages the kind of careful, nuanced reporting that builds long-term credibility. Outlets that once competed on the quality of their journalism now compete on the volume of their clicks.

The Chilling Effect on Democratic Deliberation

The consequences of media mistrust extend far beyond the news industry itself. A functioning democracy depends on citizens having access to accurate information about public affairs. When a substantial portion of the electorate believes that all news is biased, the foundations of democratic deliberation begin to erode.

The most immediate effect is the difficulty of establishing shared factual premises for political debate. In healthy democracies, citizens may disagree about values and priorities, but they generally agree about basic facts. When one portion of the electorate believes that climate change is a hoax invented by liberal scientists and another portion believes it is an existential threat requiring immediate action, meaningful policy debate becomes almost impossible. Both sides are operating from different factual foundations, and there is no neutral arbiter who can adjudicate their disputes.

The decline of trust in media also creates openings for conspiracy theories and misinformation to flourish. When people do not trust established news sources, they become more susceptible to claims from alternative sources, regardless of those sources’ reliability. The result has been an explosion of false claims circulating as “news” on social media, in email forwards, and on partisan websites. Some of these claims are harmless hoaxes; others are deliberately designed to manipulate public opinion for political or financial gain.

The problem is compounded by the phenomenon of “both-sidesism” in mainstream journalism. In an effort to appear balanced, journalists often present opposing viewpoints as equally credible, even when the weight of evidence strongly favors one side. This approach, intended to demonstrate impartiality, often has the effect of creating false equivalence and undermining public understanding. When journalists present “balanced” coverage of issues where the facts are clear, they inadvertently signal to audiences that the truth is genuinely uncertain, encouraging skepticism of expert consensus.

The effects of media mistrust on political participation are also significant but underappreciated. Research suggests that citizens who distrust the media are less likely to vote, less likely to engage in political discussion, and less likely to trust democratic institutions more broadly. When people believe that their political process is rigged and that the information they receive is manipulated, they become less invested in the system that produces such manipulated outcomes. This creates a vicious cycle in which media mistrust leads to political disengagement, which in turn creates openings for anti-democratic movements that promise to disrupt the status quo.

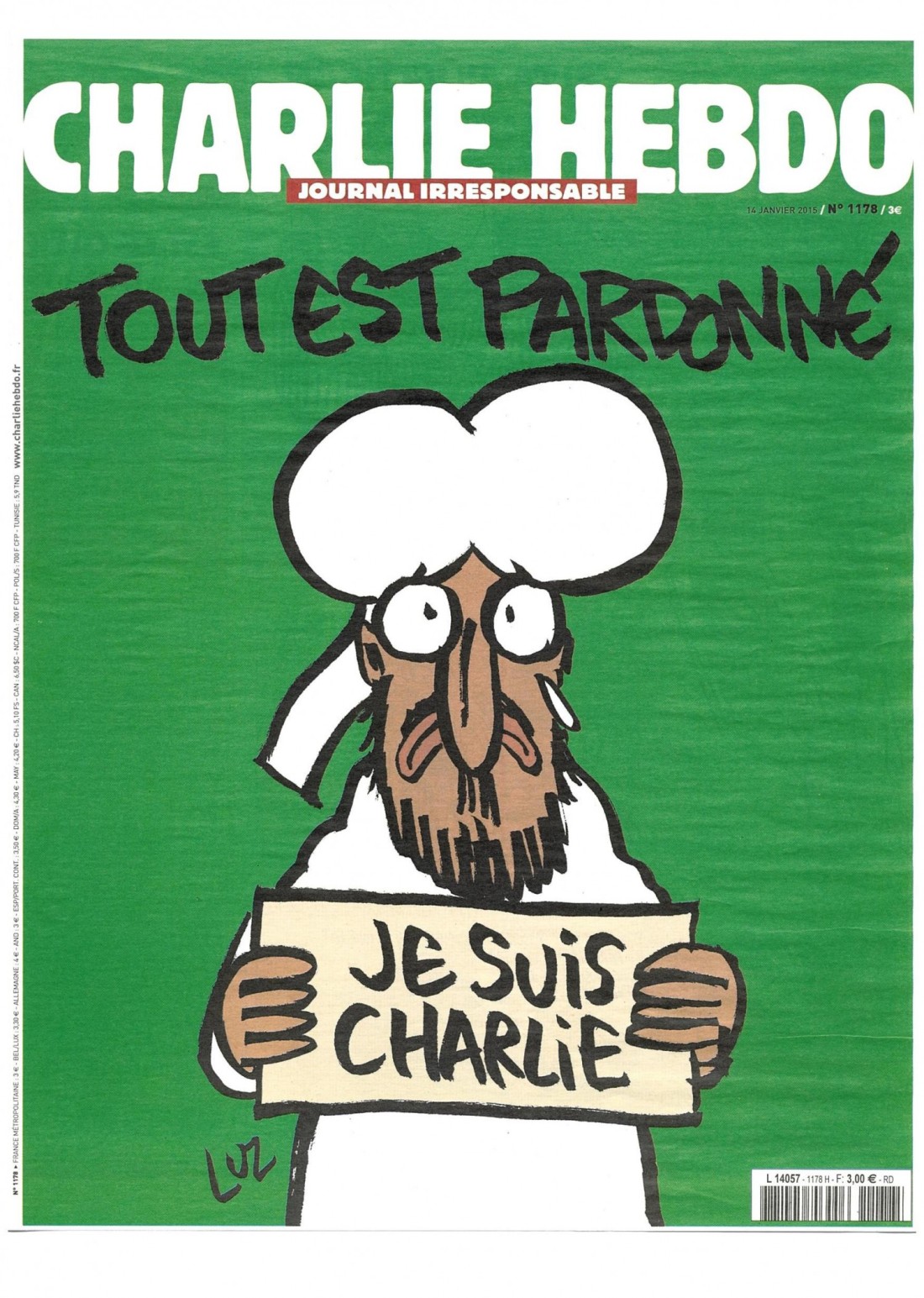

The international implications are equally troubling. American media mistrust has been studied extensively, but similar dynamics are playing out across the democratic world. In Europe, right-wing populist movements have made hostility to mainstream media a core element of their political programs. In Latin America, governments have used the decline of traditional media to establish control over the information landscape. The global nature of the phenomenon suggests that it reflects deeper structural changes in how humans consume and process information, rather than the peculiarities of any single political system.

The Rise of Alternative Media and Its Discontents

The crisis of mainstream media has created opportunities for alternative sources of news and analysis. Independent journalists, podcasters, Substack writers, and YouTube creators have stepped into the void left by declining traditional outlets, offering perspectives that their audiences perceive as more authentic and trustworthy than what they find in mainstream publications.

The growth of this alternative media ecosystem has been remarkable. According to recent estimates, more than 50 million Americans now get their news from podcasts, with many of the most popular shows attracting audiences in the millions. Substack, the newsletter platform, has become home to thousands of independent journalists who have left traditional outlets to build direct relationships with readers. YouTube hosts a thriving community of political commentators who attract views that rival those of cable news programs.

These alternative sources offer genuine advantages over traditional media. Without the need to appeal to mass audiences or satisfy corporate advertisers, independent journalists can pursue stories that legacy outlets might avoid. They can take positions that would be considered too controversial for mainstream publications. They can build communities of engaged readers who share their values and priorities. For many audiences, this direct connection feels more authentic than the mediated relationship with readers that traditional journalism provides.

But the alternative media ecosystem also has significant limitations. The same independence that allows alternative journalists to pursue unpopular stories also frees them from the editorial oversight and fact-checking processes that, for all their flaws, have historically served as a check on misinformation. Without the institutional constraints of traditional journalism, there is no guarantee that alternative sources will be more accurate than the outlets they criticize.

In fact, research suggests that many alternative media sources are actually less reliable than traditional outlets. Because they depend on engagement and controversy for survival, they have incentives to produce sensationalist content that reinforces their audiences’ existing beliefs. Some have become generators of conspiracy theories and misinformation, spreading claims that would never pass through the editorial filters of mainstream publications.

The personality-driven nature of alternative media creates additional concerns. When audiences tune in to a particular podcaster or newsletter writer, they are often following a personality rather than an institution. This creates strong parasocial relationships that can be difficult to question or challenge. When the personality makes errors or spreads misinformation, their followers are often reluctant to accept criticism, seeing it as an attack on their chosen information source.

The economic model of alternative media also raises concerns about sustainability and independence. While Substack writers theoretically have direct relationships with paying subscribers, the platform’s algorithms and business model create their own pressures. Writers who want to grow their audiences must optimize for engagement, just as traditional outlets optimized for advertising. The result may be a different set of distortions rather than a genuinely independent alternative.

Platform Power and the Algorithmic Shaping of Reality

Perhaps no factor has been more important in reshaping the media landscape than the rise of digital platforms. Google and Facebook now dominate the flow of information online, directing billions of users to news articles, videos, and posts every day. The algorithms these companies have developed to maximize user engagement have profound effects on what information reaches which audiences.

The platform revolution fundamentally disrupted the relationship between news producers and consumers. In the traditional media model, editors served as gatekeepers, deciding which stories would reach audiences based on their news judgment. In the platform model, algorithms make these decisions based on predicted user engagement. Stories that generate clicks, shares, and comments are amplified; stories that fail to engage are buried, regardless of their importance or accuracy.

This algorithmic gatekeeping has created a media environment optimized for emotional impact rather than informational value. Research has consistently found that content that provokes strong emotions—anger, fear, surprise—receives more engagement than content that provides nuanced information. Platforms have become, in effect, engines for the production and distribution of outrage.

The consequences for public discourse have been severe. Political content on social media tends to be more extreme than content in traditional media, because extreme content generates more engagement. This creates pressure on political actors to adopt more extreme positions, knowing that moderation will be punished algorithmically. The result is a political environment characterized by escalating confrontation and declining tolerance for compromise.

Platform algorithms have also contributed to the fragmentation of public discourse. Because they optimize for individual engagement rather than shared information, algorithms tend to create filter bubbles in which users encounter primarily content that reinforces their existing beliefs. While some scholars question how effective these bubbles actually are—users often encounter diverse content despite algorithmic sorting—the perception of bubble existence may be as important as the reality. When people believe they are in an information bubble, they become more skeptical of information from outside their bubble.

The platforms themselves have become increasingly important actors in the media ecosystem. Their decisions about content moderation, algorithmic amplification, and creator monetization shape what information can reach audiences and under what conditions. These decisions are often opaque, inconsistent, and subject to political pressure. The platforms have become, in effect, unelected regulators of public discourse, with powers that would have been unimaginable for traditional media gatekeepers.

Recent efforts to reform platform power have had limited success. Legislative proposals to regulate algorithms, require transparency, or break up dominant companies have faced intense lobbying opposition. The platforms have successfully positioned themselves as neutral conduits rather than active shapers of information, making it difficult to impose accountability for their algorithmic choices. The result is a media environment in which the most powerful information gatekeepers are effectively unaccountable to democratic processes.

What Can Be Done? Paths Toward Restoring Trust

The crisis of media trust is not inevitable, and it is not irreversible. But addressing it will require sustained effort across multiple fronts: from platform reform to media literacy education to institutional innovation. There is no single solution, but there are concrete steps that can begin to restore the conditions for healthy democratic discourse.

Platform reform is essential. The concentration of information flow in the hands of a few giant companies creates risks that cannot be addressed through market competition or voluntary self-regulation. Legislative action is needed to require algorithmic transparency, prevent anticompetitive practices, and ensure that platforms cannot arbitrarily suppress or amplify particular viewpoints. The European Union’s Digital Services Act represents one model for such regulation, though its effectiveness remains to be seen.

Media literacy education can help citizens become more sophisticated consumers of information. Teaching people how to evaluate sources, recognize logical fallacies, and distinguish between fact and opinion can build resilience against misinformation. But media literacy alone is insufficient; expecting individuals to solve systemic problems through personal vigilance is both unfair and unrealistic. Media literacy must be part of a broader package of reforms.

Supporting public media is crucial. In many countries, public broadcasting has served as a source of trusted, non-partisan news that serves all citizens regardless of their political views. But public media faces political pressure and budget cuts that undermine its effectiveness. Strengthening public media institutions, protecting them from political interference, and ensuring they have adequate resources to produce quality journalism should be priorities for reformers.

Independent journalism needs sustainable business models. The nonprofit news movement, exemplified by organizations like ProPublica, The Texas Tribune, and local investigative newsrooms, has shown that quality journalism can survive outside the traditional advertising model. Supporting these organizations through philanthropy, foundation grants, and subscription revenues can help preserve the capacity for accountability journalism.

Finally, political leaders must stop attacking the press. While politicians have always complained about media coverage, the current intensity of anti-media rhetoric is unprecedented and dangerous. When leaders declare the press to be enemies of the people, they undermine the foundations of democratic accountability. Restoring a culture in which journalistic scrutiny is seen as essential rather than adversarial is a collective project that requires leadership from all parts of the political spectrum.

The Imperative of Informed Citizenship

In the final analysis, the crisis of media trust reflects a broader crisis of citizenship. Democratic governance depends on citizens who are willing and able to engage critically with information about public affairs. When citizens lose faith in the possibility of accurate reporting, they lose motivation to participate in democratic processes. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle in which declining trust leads to declining participation, which leads to declining accountability, which leads to declining trust.

Breaking this cycle will require more than institutional reforms. It will require a cultural shift in how Americans—and citizens of democratic societies more broadly—think about their role in governance. Citizens must come to see themselves not as passive consumers of political spectacles but as active participants in democratic deliberation. They must demand better from their information sources and from themselves.

The stakes could not be higher. In an era of global challenges—from climate change to pandemic disease to nuclear proliferation—the need for informed public deliberation is acute. The decisions made in the coming decades will shape human civilization for centuries to come. Making those decisions wisely requires an informed citizenry with access to accurate information and the capacity to evaluate competing claims.

The crisis of media trust is, ultimately, a crisis of democracy itself. Addressing it will require all of the tools at our disposal: technological innovation, institutional reform, educational improvement, and cultural change. There is no shortcut, and there is no single solution. But the first step is recognizing the depth and urgency of the problem.

The 31 percent confidence figure from Gallup should serve as a wake-up call. It is not a natural disaster that must be endured but a social problem that can be solved. Whether we will summon the collective will to solve it is the central question facing democratic societies in the years ahead.

Bernd Pulch is a political commentator, satirist, and investigative journalist covering lawfare, media control, and German politics. His work examines how legal systems are weaponized and what democracy loses when courts become battlefields. Full bio →

This investigation is reader-supported. Secure donations via Monero →

Tags: media trust, media mistrust 2026, Gallup media confidence, political polarization, platform algorithms, alternative media, news deserts, nonprofit journalism, public media, Digital Services Act, fake news, misinformation, hostile media effect, both-sidesism, journalism crisis

Chinese President Xi Jinping and British Prime Minister David Cameron. Photo: UK Government / Georgina Coupe

Chinese President Xi Jinping and British Prime Minister David Cameron. Photo: UK Government / Georgina Coupe Files show a number of luxury yachts bought and sold through offshore companies. Photo: Twiga269 / Flickr

Files show a number of luxury yachts bought and sold through offshore companies. Photo: Twiga269 / Flickr Argentine soccer player Lionel Messi. Photo: Shutterstock / CP DC Press

Argentine soccer player Lionel Messi. Photo: Shutterstock / CP DC Press Employees of Mossack Fonseca were among those arrested by Brazilian police as part of Operation Car Wash. Image: RedeTV

Employees of Mossack Fonseca were among those arrested by Brazilian police as part of Operation Car Wash. Image: RedeTV Mossack Fonseca co-founder Jürgen Mossack.

Mossack Fonseca co-founder Jürgen Mossack. Mossack Fonseca co-founder Ramón Fonseca.

Mossack Fonseca co-founder Ramón Fonseca. Gold miners in South Africa. Photo: AP Photo / Themba Hadebe

Gold miners in South Africa. Photo: AP Photo / Themba Hadebe Close allies of Russian President Vladimir Putin make extensive use of offshore holdings to shuffle large sums of money. Photo: AP Photo / Krill Kudryavtsev

Close allies of Russian President Vladimir Putin make extensive use of offshore holdings to shuffle large sums of money. Photo: AP Photo / Krill Kudryavtsev Iceland Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson and his wife Anna Sigurlaug Pálsdóttir.

Iceland Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson and his wife Anna Sigurlaug Pálsdóttir. The Ethan Allen tour boat brought to the surface after sinking in Lake George, New York. Photo: AP Photo / Mary Altaffer

The Ethan Allen tour boat brought to the surface after sinking in Lake George, New York. Photo: AP Photo / Mary Altaffer A sign for MF Corporate Services outside a buisness complex in Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo: McClatchy / Ronda Churchill

A sign for MF Corporate Services outside a buisness complex in Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo: McClatchy / Ronda Churchill

On January 19, 2009, Russian human rights attorney

On January 19, 2009, Russian human rights attorney

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict49.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict107.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict108.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict109.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict50.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict51.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict106.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict11.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict15.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict17.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict18.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict19.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict12.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict14.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict2.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict3.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict4.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict1.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict0.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict5.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict6.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict7.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict8.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict9.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict10.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict13.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict110.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/free-syria/pict111.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict154.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict153.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict152.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict135.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict136.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict137.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict138.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict140.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict144.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict139.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict142.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict141.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict143.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict145.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict147.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict148.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict146.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict149.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict150.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/pussy-riot/pict151.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012/06/wikileaks-trap1.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012/06/wikileaks-trap2.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict0.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict1.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict2.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict13.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict10.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict9.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict11.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict7.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict6.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict5.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict3.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/fodor/pict8.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict35.jpg) A worker is given a radiation screening as he enters the emergency operation center at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. Japan next month marks one year since the March 11 tsunami and earthquake, which triggered the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl in 1986. (Issei Kato)

A worker is given a radiation screening as he enters the emergency operation center at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. Japan next month marks one year since the March 11 tsunami and earthquake, which triggered the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl in 1986. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict24.jpg) Destroyed unit 3 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Destroyed unit 3 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict29.jpg) Workers wearing protective suits and masks work atop of No. 4 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Workers wearing protective suits and masks work atop of No. 4 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict25.jpg) A worker wearing protective suit and mask works atop of destroyed unit 4 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

A worker wearing protective suit and mask works atop of destroyed unit 4 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict26.jpg) Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s reactor buildings, from right, No.4, No.3, and No.2 [damaged No.2 has been enclosed, see following photo], are seen at tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s reactor buildings, from right, No.4, No.3, and No.2 [damaged No.2 has been enclosed, see following photo], are seen at tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict31.jpg) The unit 2 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen through a bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

The unit 2 reactor building of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen through a bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict28.jpg) Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen from bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is seen from bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict34.jpg) Workers wearing protective suits and masks construct water tanks, seen through a bus window during a press tour at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Workers wearing protective suits and masks construct water tanks, seen through a bus window during a press tour at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict33.jpg) Unit 6, left, and unit 5 reactor buildings of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant are seen through a bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)

Unit 6, left, and unit 5 reactor buildings of Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s tsunami-crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant are seen through a bus window during a press tour in Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan, Monday, Feb. 20, 2012. (Issei Kato)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict32.jpg) Trucks are overturned before the Unit 4 reactor building of stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant of Tokyo Electric Power Co., in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)

Trucks are overturned before the Unit 4 reactor building of stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant of Tokyo Electric Power Co., in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict27.jpg) Stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant buildings of Tokyo Electric Power Co., are seen in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)

Stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant buildings of Tokyo Electric Power Co., are seen in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/daiichi-022012/pict30.jpg) A journalist checks radiation level with her dosimeter near stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant of Tokyo Electric Power Co., during a press tour led by TEPCO officials, in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)

A journalist checks radiation level with her dosimeter near stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant of Tokyo Electric Power Co., during a press tour led by TEPCO officials, in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2012. (Yoshikazu Tsuno)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict19.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Dmitry Polosov, 25, a scientist, holds a poster reading “for the honor society, for responsible for every act, for freedom of knowledge, for good in the hearts, for love in the minds” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow. Despite temperatures plunging to minus 20 C (minus 4 F), thousands of Russians took to the streets of Moscow to challenge Putin’s bid.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Dmitry Polosov, 25, a scientist, holds a poster reading “for the honor society, for responsible for every act, for freedom of knowledge, for good in the hearts, for love in the minds” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow. Despite temperatures plunging to minus 20 C (minus 4 F), thousands of Russians took to the streets of Moscow to challenge Putin’s bid.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict12.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Tatyana Lazareva, 46, a television presenter, holds a poster reading “move on to the next level” as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Tatyana Lazareva, 46, a television presenter, holds a poster reading “move on to the next level” as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict14.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Vyacheslav Barannikov, 38, an engineer, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Vyacheslav Barannikov, 38, an engineer, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict8.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Yekaterina, 26, a translator, wears a scarf with the name of presidential contender Mikhail Prokhorov as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Yekaterina, 26, a translator, wears a scarf with the name of presidential contender Mikhail Prokhorov as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict9.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Kirill, 26, a scientist, wears a scarf with the name of presidential contender Mikhail Prokhorov as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Kirill, 26, a scientist, wears a scarf with the name of presidential contender Mikhail Prokhorov as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict13.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Nina Lipkina, 53, unemployed, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Nina Lipkina, 53, unemployed, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict10.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Gennady, 73, a pensioner, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Gennady, 73, a pensioner, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict17.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Yana Romanova, 35, a designer, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Yana Romanova, 35, a designer, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as she poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict11.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Artur Gazarov, 43, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Artur Gazarov, 43, wears a white ribbon reading “For Russia without Putin” as he poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict20.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Liliya Pevter, 62, a pensioner, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Liliya Pevter, 62, a pensioner, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict15.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Igor German, 23, an engineer, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Igor German, 23, an engineer, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict16.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Mikhail Shats, 46, an actor, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Mikhail Shats, 46, an actor, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/putin-protest/pict18.jpg) In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Dima Kuzmich, 29, a bank employee, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

In this Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 photo, Dima Kuzmich, 29, a bank employee, poses in front of a white canvas placed in the middle of the crowd at a massive protest against Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s rule in Bolotnaya square in Moscow.

Preet Bhrara, Verfasser der Anklage

Preet Bhrara, Verfasser der Anklage![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict73.jpg) Megaupload.com employees Bram van der Kolk, also known as Bramos, left, Finn Batato,second from left, Mathias Ortmann and founder, former CEO and current chief innovation officer of Megaupload.com Kim Dotcom (also known as Kim Schmitz and Kim Tim Jim Vestor), right, appear in North Shore District Court in Auckland, New Zealand, Friday, Jan. 20, 2012.

Megaupload.com employees Bram van der Kolk, also known as Bramos, left, Finn Batato,second from left, Mathias Ortmann and founder, former CEO and current chief innovation officer of Megaupload.com Kim Dotcom (also known as Kim Schmitz and Kim Tim Jim Vestor), right, appear in North Shore District Court in Auckland, New Zealand, Friday, Jan. 20, 2012. German Internet millionaire Kim Schmitz arrives for. a trial at a district court in Munich in these May 27, 2002 file photos. New Zealand police broke through electronic locks and cut their way into a mansion safe room to arrest the alleged kingpin of an international Internet copyright theft case and seize millions of dollars worth of cars, artwork and other goods. German national Schmitz, also known as Kim Dotcom, was one of four men arrested in Auckland on January 20, 2012, in an investigation of the Megaupload.com website led by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Reuters

German Internet millionaire Kim Schmitz arrives for. a trial at a district court in Munich in these May 27, 2002 file photos. New Zealand police broke through electronic locks and cut their way into a mansion safe room to arrest the alleged kingpin of an international Internet copyright theft case and seize millions of dollars worth of cars, artwork and other goods. German national Schmitz, also known as Kim Dotcom, was one of four men arrested in Auckland on January 20, 2012, in an investigation of the Megaupload.com website led by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Reuters![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict75.jpg) In this April 30, 2007 file photo, attorney Robert Bennett speaks in Washington. Bennett, one of the nation’s most prominent defense lawyers will represent file-sharing website Megaupload on charges that the company used its popular site to orchestrate a massive piracy scheme that enabled millions of illegal downloads of movies and other content. (J. Scott Applewhite)

In this April 30, 2007 file photo, attorney Robert Bennett speaks in Washington. Bennett, one of the nation’s most prominent defense lawyers will represent file-sharing website Megaupload on charges that the company used its popular site to orchestrate a massive piracy scheme that enabled millions of illegal downloads of movies and other content. (J. Scott Applewhite)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict72.jpg) Tow trucks wait to remove vehicles from Kim Dotcom’s house in Coatesville, north west of Auckland, New Zealand Friday, Jan. 20, 2012. Police arrested founder Kim Dotcom and three employees of Megaupload.com, a giant Internet file-sharing site, on U.S. accusations that they facilitated millions of illegal downloads of films, music and other content costing copyright holders at least $500 million in lost revenue. (Natalie Slade)

Tow trucks wait to remove vehicles from Kim Dotcom’s house in Coatesville, north west of Auckland, New Zealand Friday, Jan. 20, 2012. Police arrested founder Kim Dotcom and three employees of Megaupload.com, a giant Internet file-sharing site, on U.S. accusations that they facilitated millions of illegal downloads of films, music and other content costing copyright holders at least $500 million in lost revenue. (Natalie Slade)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict78.jpg) A general view shows the Dotcom Mansion, home of Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom, in Coatesville, Auckland, January 21, 2012. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. The U.S. Department of Justice announced the indictment and arrests of four company executives in New Zealand on Friday as debate over online piracy reaches fever pitch in Washington where lawmakers are trying to craft tougher legislation. Reuters

A general view shows the Dotcom Mansion, home of Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom, in Coatesville, Auckland, January 21, 2012. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. The U.S. Department of Justice announced the indictment and arrests of four company executives in New Zealand on Friday as debate over online piracy reaches fever pitch in Washington where lawmakers are trying to craft tougher legislation. Reuters![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict79.jpg) A broken intercom system is seen after a police raid at Dotcom Mansion, home of accused Kim Dotcom, who founded the Megaupload.com site and ran it from the $30 million mansion in Coatesville, Auckland January 21, 2012. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. New Zealand police on Friday raided a mansion in Auckland and arrested Kim Dotcom, also known as Kim Schmitz, 37, a German national with New Zealand residency. Reuters

A broken intercom system is seen after a police raid at Dotcom Mansion, home of accused Kim Dotcom, who founded the Megaupload.com site and ran it from the $30 million mansion in Coatesville, Auckland January 21, 2012. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. New Zealand police on Friday raided a mansion in Auckland and arrested Kim Dotcom, also known as Kim Schmitz, 37, a German national with New Zealand residency. Reuters![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict77.jpg) An entrance to Megaupload’s office at a hotel in Hong Kong is seen in this Hong Kong government handout photo released late January 20, 2012. The Hong Kong government said on Friday over HK$300 million ($38.4 million) worth of proceeds from Megaupload were seized in the country in joint operations by Hong Kong customs and U.S. authorities. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. Reuters

An entrance to Megaupload’s office at a hotel in Hong Kong is seen in this Hong Kong government handout photo released late January 20, 2012. The Hong Kong government said on Friday over HK$300 million ($38.4 million) worth of proceeds from Megaupload were seized in the country in joint operations by Hong Kong customs and U.S. authorities. The U.S. government shut down the Megaupload.com content sharing website, charging its founders and several employees with massive copyright infringement, the latest skirmish in a high-profile battle against piracy of movies and music. Reuters![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict74.jpg) In this photo taken Friday, Jan. 20,2012, provided by the Government Information Service in Hong Kong, large-scale high-speed servers set up at Megaupload’s office are shown inside a hotel room in Hong Kong. Customs officials said they seized more than $42.5 million in assets from the Hong Kong based company. The U.S. government shut down Megaupload’s file-sharing website on Thursday, alleging that the company facilitated illegal downloads of copyrighted movies and other content.

In this photo taken Friday, Jan. 20,2012, provided by the Government Information Service in Hong Kong, large-scale high-speed servers set up at Megaupload’s office are shown inside a hotel room in Hong Kong. Customs officials said they seized more than $42.5 million in assets from the Hong Kong based company. The U.S. government shut down Megaupload’s file-sharing website on Thursday, alleging that the company facilitated illegal downloads of copyrighted movies and other content.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/megaupload/pict76.jpg) A masked hacker, part of the Anonymous group, hacks the French presidential Elysee Palace website on January 20, 2012 near the eastern city of Lyon. Anonymous, which briefly knocked the FBI and Justice Department websites offline in retaliation for the US shutdown of file-sharing site Megaupload, is a shadowy group of international hackers with no central hierarchy. On the left screen, an Occupy mask is seen. Getty

A masked hacker, part of the Anonymous group, hacks the French presidential Elysee Palace website on January 20, 2012 near the eastern city of Lyon. Anonymous, which briefly knocked the FBI and Justice Department websites offline in retaliation for the US shutdown of file-sharing site Megaupload, is a shadowy group of international hackers with no central hierarchy. On the left screen, an Occupy mask is seen. Getty![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict29.jpg) Italian naval divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening. Italian naval divers on Tuesday exploded holes in the hull of a cruise ship grounded off a Tuscan island to speed the search for 29 missing people while seas were still calm. One official said there was still a “glimmer of hope” that survivors could be found.

Italian naval divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening. Italian naval divers on Tuesday exploded holes in the hull of a cruise ship grounded off a Tuscan island to speed the search for 29 missing people while seas were still calm. One official said there was still a “glimmer of hope” that survivors could be found.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict30.jpg) Italian naval divers work on the cruise ship Costa Concordia Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening.

Italian naval divers work on the cruise ship Costa Concordia Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict31.jpg) The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening.

The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012, after running aground on the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, on Friday evening.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict32.jpg) Italian navy divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia in the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012.

Italian navy divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia in the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2012.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict12.jpg) Oil removal ships near the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side Monday, Jan. 16, 2012, after running aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, last Friday night. The rescue operation was called off mid-afternoon Monday after the Costa Concordia shifted a few inches (centimeters) in rough seas. The fear is that if the ship shifts significantly, some 500,000 gallons of fuel may begin to leak into the pristine waters. (Gregorio Borgia)

Oil removal ships near the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side Monday, Jan. 16, 2012, after running aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, last Friday night. The rescue operation was called off mid-afternoon Monday after the Costa Concordia shifted a few inches (centimeters) in rough seas. The fear is that if the ship shifts significantly, some 500,000 gallons of fuel may begin to leak into the pristine waters. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict24.jpg) The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side Monday, Jan.16, 2012, after running aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, last Friday. The rescue operation was called off mid-afternoon Monday after the Costa Concordia shifted a few inches (centimeters) in rough seas. The fear is that if the ship shifts significantly, some 500,000 gallons of fuel may begin to leak. (Gregorio Borgia)

The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side Monday, Jan.16, 2012, after running aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, last Friday. The rescue operation was called off mid-afternoon Monday after the Costa Concordia shifted a few inches (centimeters) in rough seas. The fear is that if the ship shifts significantly, some 500,000 gallons of fuel may begin to leak. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict22.jpg) In this underwater photo released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 the cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side, after it ran aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy. (Italian Coast Guard)

In this underwater photo released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 the cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side, after it ran aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy. (Italian Coast Guard)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict23.jpg) In this underwater photo taken on Jan. 13 and released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 a view of the cruise ship Costa Concordia, after it ran aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for. (Italian Coast Guard)

In this underwater photo taken on Jan. 13 and released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 a view of the cruise ship Costa Concordia, after it ran aground near the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for. (Italian Coast Guard)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict17.jpg) In this photo released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 a coast guard scuba diver makes his way through floating pieces of furniture inside the cruise ship Costa Concordia Sunday Jan. 15. 2012,after it run aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for.

In this photo released by the Italian Coast Guard Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 a coast guard scuba diver makes his way through floating pieces of furniture inside the cruise ship Costa Concordia Sunday Jan. 15. 2012,after it run aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict15.jpg) Italian rescue personnel are seen atop the Costa Concordia cruise liner, two days after it ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. The captain of a cruise liner that ran aground and capsized off the Tuscan coast faced accusations from authorities and passengers that he abandoned ship before everyone was safely evacuated as rescuers found another body on the overturned vessel. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian rescue personnel are seen atop the Costa Concordia cruise liner, two days after it ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. The captain of a cruise liner that ran aground and capsized off the Tuscan coast faced accusations from authorities and passengers that he abandoned ship before everyone was safely evacuated as rescuers found another body on the overturned vessel. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict25.jpg) Italian firefighters scuba divers work on the cruise ship Costa Concordia two days after it run aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian firefighters scuba divers work on the cruise ship Costa Concordia two days after it run aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. Italian rescue officials say a passenger’s body has been found in the wreckage of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, raising to six the number of confirmed dead in the disaster. Sixteen people remain unaccounted-for. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict26.jpg) Italian rescue divers approach the Costa Concordia cruise liner, two days after it run aground off tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. The captain of a cruise liner that ran aground and capsized off the Tuscan coast faced accusations from authorities and passengers that he abandoned ship before everyone was safely evacuated as rescuers found another body on the overturned vessel. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian rescue divers approach the Costa Concordia cruise liner, two days after it run aground off tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Monday, Jan. 16, 2012. The captain of a cruise liner that ran aground and capsized off the Tuscan coast faced accusations from authorities and passengers that he abandoned ship before everyone was safely evacuated as rescuers found another body on the overturned vessel. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict8.jpg) Italian Firefighters scuba divers work aboard the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. Firefighters worked Sunday to rescue a crew member with a suspected broken leg from the overturned hulk of the cruise liner, 36 hours after it ran aground. More than 40 people are still unaccounted-for. (Remo Casilli)

Italian Firefighters scuba divers work aboard the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. Firefighters worked Sunday to rescue a crew member with a suspected broken leg from the overturned hulk of the cruise liner, 36 hours after it ran aground. More than 40 people are still unaccounted-for. (Remo Casilli)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict16.jpg) Italian firefighters approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. (Remo Casilli)

Italian firefighters approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. (Remo Casilli)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict11.jpg) Italian firefighters’ scuba divers approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian firefighters’ scuba divers approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict6.jpg) Italian firefighters scuba divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side, the day after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian firefighters scuba divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side, the day after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict33.jpg) Italian Navy scuba divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side, the day after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian Navy scuba divers approach the cruise ship Costa Concordia leaning on its side, the day after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict7.jpg)

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict13.jpg) Investigators approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which leans on its starboard side after running aground in the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Costa Concordia cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)

Investigators approach the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which leans on its starboard side after running aground in the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Costa Concordia cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict14.jpg) Firefighters work on the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia the day after it run aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Italian Coast Guard says its divers have found two more bodies aboard the stricken Costa Concordia cruise ship. The discovery of the bodies brings to five the number of known dead after the luxury ship ran aground with some 4,200 people aboard on Friday night. (Andrea Sinibaldi)

Firefighters work on the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia the day after it run aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Italian Coast Guard says its divers have found two more bodies aboard the stricken Costa Concordia cruise ship. The discovery of the bodies brings to five the number of known dead after the luxury ship ran aground with some 4,200 people aboard on Friday night. (Andrea Sinibaldi)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict28.jpg) The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side, after it ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)

The cruise ship Costa Concordia leans on its side, after it ran aground off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. A helicopter on Sunday airlifted a third survivor from the capsized hulk of a luxury cruise ship 36 hours after it ran aground off the Italian coast, as prosecutors confirmed they were investigating the captain for manslaughter charges and abandoning the ship. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict27.jpg) Italian Navy scuba divers prepare to search the wreck of the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia that ran aground in the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Costa Concordia cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian Navy scuba divers prepare to search the wreck of the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia that ran aground in the tiny Tuscan island of Isola del Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. The Costa Concordia cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict21.jpg) An Italian firefighter helicopter lifts up a person from the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground the off tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. Firefighters worked Sunday to rescue a crew member with a suspected broken leg from the overturned hulk of the luxury cruise liner Costa Concordia, 36 hours after it ran aground. More than 40 people are still unaccounted-for. (Gregorio Borgia)

An Italian firefighter helicopter lifts up a person from the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia which ran aground the off tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 15, 2012. Firefighters worked Sunday to rescue a crew member with a suspected broken leg from the overturned hulk of the luxury cruise liner Costa Concordia, 36 hours after it ran aground. More than 40 people are still unaccounted-for. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict34.jpg) Italian Coast guard personnel recovers the black box of the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)

Italian Coast guard personnel recovers the black box of the luxury cruise ship Costa Concordia after running aground the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio, Italy, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict36.jpg) Passengers of the luxury ship that ran aground off the coast of Tuscany board a bus in Porto Santo Stefano, Italy, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, gashing open the hull and taking on water, forcing some 4,200 people aboard to evacuate aboard lifeboats to a nearby island early Saturday. At least three were dead, the Italian coast guard said. Three bodies were recovered from the sea, said Coast Guard Cmdr. Francesco Paolillo. (Gregorio Borgia)

Passengers of the luxury ship that ran aground off the coast of Tuscany board a bus in Porto Santo Stefano, Italy, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, gashing open the hull and taking on water, forcing some 4,200 people aboard to evacuate aboard lifeboats to a nearby island early Saturday. At least three were dead, the Italian coast guard said. Three bodies were recovered from the sea, said Coast Guard Cmdr. Francesco Paolillo. (Gregorio Borgia)![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict18.jpg) This photo acquired by the Associated Press from a passenger of the luxury ship that ran aground off the coast of Tuscany shows rescued passengers arriving at the Giglio island harbor, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, gashing open the hull and taking on water, forcing some 4,200 people aboard to evacuate aboard lifeboats to a nearby island early Saturday. At least three were dead, the Italian coast guard said.

This photo acquired by the Associated Press from a passenger of the luxury ship that ran aground off the coast of Tuscany shows rescued passengers arriving at the Giglio island harbor, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, gashing open the hull and taking on water, forcing some 4,200 people aboard to evacuate aboard lifeboats to a nearby island early Saturday. At least three were dead, the Italian coast guard said.![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/cryptome.org/2012-info/costa-concordia/pict42.jpg) This photo acquired by the Associated Press from a passenger of the luxury ship that ran aground off the coast of Tuscany shows fellow passengers wearing life-vests on board the Costa Concordia as they wait to be evacuated, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2012. A luxury cruise ship ran aground off the coast of Tuscany, sending water pouring in through a 160-foot (50-meter) gash in the hull and forcing the evacuation of some 4,200 people from the listing vessel early Saturday, the Italian coast guard said.