Gambling addicts may want to take note of who Kim Kardashian picked to win the Super Bowl… because Lord knows this chick knows how to make a buck!

Month: January 2013

TOP-SECRET – FBI Bomb Data Center Bulletin: The Bomb Threat Challenge

FBI Bomb Data Center General Information Bulletin 2012-1

- 13 pages

- September 2012

As we enter an era in which the administration of law enforcement becomes more complicated, greater challenges are thrust not only upon police officials, but also upon the community at large. The bomb threat is one such challenge. The bomber has a distinct advantage over other criminals because he can pick his time and place from afar, and use the bomb threat as a weapon to achieve his criminal objectives. This bulletin has been prepared in order to provide law enforcement and public safety agencies with a working base from which to establish their own bomb threat response capability; and to enable these same agencies, when called upon by potential bomb or bomb threat targets in the business community, to offer assistance in developing guidelines for a bomb threat response plan.

In developing a bomb threat response plan, there are four general areas of consideration: (1) Planning and Preparation, (2) Receiving a Threat, (3) Evacuation, and (4) Search. Information presented under each of these four topics will assist in the preparation of an effective bomb threat plan. Suggested methods described in this bulletin will apply in most cases; however, specific requirements will be unique for each facility and will need to be worked out on an individual basis. Once the function of the organization, size of the facility, number of personnel, location and relation to other establishments, and available resources are evaluated; a comprehensive bomb threat plan can be formulated.

Words used in conjunction with this phase include organization, liaison, coordination, and control. Only with a properly organized plan will those affected by a bomb threat know how, when, and in what order to proceed.

Liaison should be maintained between appropriate public safety agencies and facilities likely to be subject to bomb threats or bombings; and also between public safety agencies and military Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) teams charged with responding to bombing incidents.Through such contact, it will be possible to determine what technical and training services might be needed by potential bomb threat targets. Note that while some public safety agencies may provide considerable aid in bomb threat situations, most public and private facilities must plan and carryout the major portion of the plan, including internal control and decision making. Both liaison and coordination are factors which a bomb threat plan must take into consideration, especially when neighboring establishments or businesses may share the same building. Proper coordination will assure smooth handling of the bomb threat with the least amount of inconvenience to all concerned. Control is especially important during evacuation and search efforts, and effective security will lessen the risk of an actual explosive device ever being planted.

…

RECEIVING A THREAT

In preparation for the eventuality of a telephone bomb threat, all personnel who handle incoming calls to a potential target facility should be supplied with a bomb threat checklist as shown in Figure 1. When a bomb threat is received, it may be advisable for the person receiving the call to give a prearranged signal. For instance, the signal can be as simple as holding up a red card. This would allow monitoring of the call by more than one person, and it would enable someone else to attempt to record and/or trace the telephone call.

Tape recording the call can reduce the chance or error in recording information provided in the bomb threat. It may serve as evidence valuable to the investigation and assist in evaluating the authenticity of the bomb threat.

Since local jurisdictions may have statutes restricting this sort of recording, the proper officials should be contacted prior to installation and use of such equipment. If a continuous recording setup is not deemed economically practical, a system which could be activated upon receipt of a threat call might be considered feasible. A local telephone company representative can provide information regarding specific services available. Regardless of whether the bomb threat call is to be recorded and/or monitored, the person handling it should remain calm and concentrate on the exact wording of the message, and any other details which could prove valuable in evaluating the threat.In those instances when a bomb threat has been electronically recorded, voice identification techniques may be employed. While the courts and the scientific community are divided over the reliability of “voice printing” as evidence, it can serve as an investigative tool. Upon request, the FBI will perform audio examinations, for the purpose of investigative leads only, for any law enforcement agency. Departments interested in this service may contact their local FBI Field Office for further assistance.

Although comprising a smaller percentage of bomb threats, the written threat must be evaluated as carefully as one received over the telephone or the Internet. Written bomb threats often provide excellent document-type evidence. Once a written threat is recognized, further handling should be avoided in order to preserve fingerprints, handwriting, typewriting, postmarks, and other markings for appropriate forensic examination. This may be accomplished by immediately placing each item (i.e., threat documents, mail envelope, etc.) in separate protective see through covers, allowing further review of the pertinent information without needless handling. In order to effectively trace such a bomb threat and identify its writer, it is imperative to save all evidentiary items connected with the threat.

Regardless of how the bomb threat is received (e.g., e-mail, telephone, written), the subsequent investigation is potentially an involved and complex one requiring a substantial degree of investigative competency in order to bring the case to a successful conclusion. Cognizant of this, and of the fact that useful evidence regarding the threat seldom proceeds past the bomb threat stage, the efficient accumulation and preservation of evidence cannot be over stressed.

After a bomb threat has been received, the next step is to immediately notify the people responsible for carrying out the bomb threat response plan. During the planning phase, it is important to prepare a list setting forth those individuals and agencies to be notified in the event of a bomb threat. In addition to those people mentioned previously, the police department, fire department, FBI and other Federal public assistance agencies, medical facilities, neighboring businesses, employee union representatives, and local utility companies are among those whose emergency contact information should be included on such a list.

The bomb threat must now be evaluated for its potential authenticity. Factors involved in such an evaluation are formidable, and any subsequent decision is often based on little reliable information. During this decision making process, until proven otherwise, each threat should be treated as though it involved an actual explosive device; even though bomb threats in which an IED is present comprise a small percentage.

Monty Python Live Hollywood Bowl – Pope and Michaelangelo

Monty Python Live Hollywood Bowl

http://www.amazon.com/Complete-Monty-Pythons-Flying-Circus/dp/B001E77XNA/ref=…

Video – Confirmed – Ukraine ex-policeman jailed for murder of journalist Gongadze

http://www.euronews.com/ A former Ukrainian police officer has been jailed for life for the murder of a campaigning journalist Georgiy Gongadze in 2000.

General Oleksiy Pukach implied in court that others, including ex-President Leonid Kuchma, were equally guilty.

A case against the former leader was dismissed two years ago.

Gongadze wrote about political corruption and crime.

The discovery of the 31-year-old’s headless body sparked a wave of public anger which eventually led to the “Orange Revolution”.

His widow’s lawyer said she intended to appeal, arguing that the court has failed to determine the motives for the killing.

Find us on:

Youtube http://bit.ly/zr3upY

Facebook http://www.facebook.com/euronews.fans

Twitter http://twitter.com/euronews

SECRET – Iranian Hackers Target US-UK Joint Operations

Iranian Hackers Target US-UK Joint Operations

A sends:

Source : http://www.rce.ir/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=245#p860

An observer we trust has let us know that in an underground Iranian hacker and reverse engineering forum, one article shows some guys have been up to no good against US-UK Joint Operations and hacked into the Waves as well as the C4I system.

Ironically, there is a link and quote from cryptome.us [link added by Cryptome] regarding IRGC’s drones flying over US carriers and put both conclusions together in a way that reader, indirectly, understands that military SATCOMS and JTRS terrestrial (say military VHF) are not safe for US-UK and to our understanding they could easily use these capabilities to grab scores from catastrophic events. The fact Iran is still talking to 5+1 in addition to these efforts, to the best of our analysis, are Iranian Deterrence.

TMZ – Hulk Hogan: Brooke Hogan’s SEXY Legs!

Hulk Hogan is catching some heat for tweeting a picture of his daughter’s sexy legs in a short skirt. Is Hulk just being a proud parent or just REALLY, SUPER CREEPY?

PI-Restricted U.S. Army Training for Reconnaissance Troop and Below in Urban Operations

TC 90-5 Training for Reconnaissance Troop and Below in Urban Operations

- 116 pages

- Distribution authorized to U.S. government agencies and their contractors only to protect technical or operational information that is for official government use.

- February 2010

- 5.09 MB

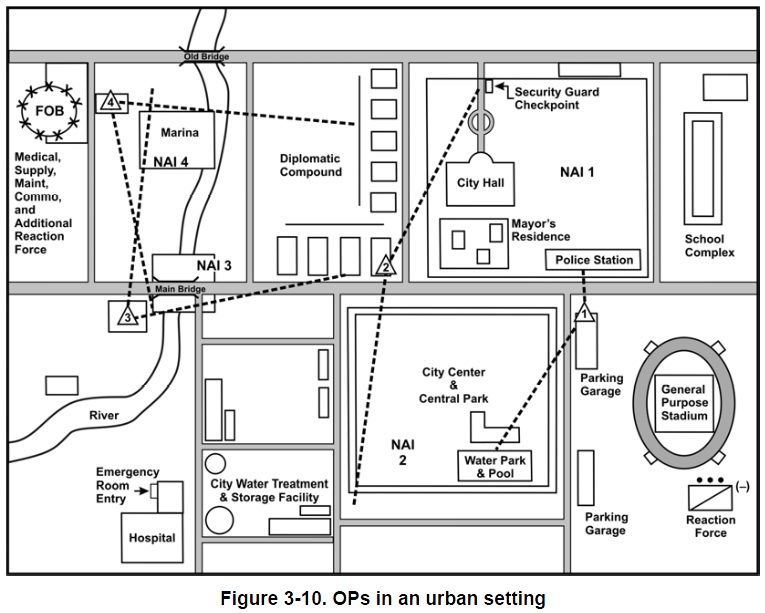

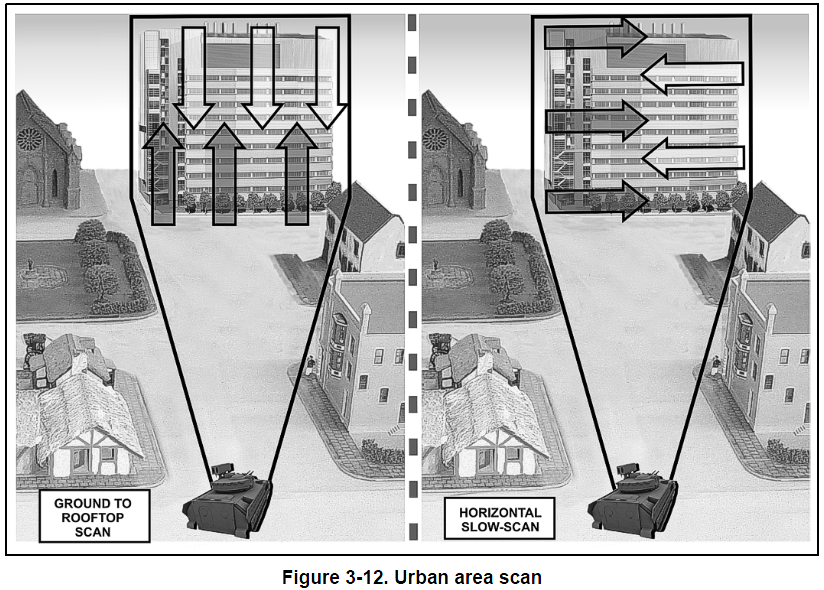

Because the operational environment (OE) requires Army forces to operate in urban areas, commanders must have accurate information on the complex human elements, infrastructure, and physical terrain that make up the urban environment. The limits on imagery and electronic reconnaissance and surveillance (R&S) capabilities place a premium on human-based visual reconnaissance. Reconnaissance troops and platoons must be trained to gather and analyze the necessary information and provide it to their commanders and higher headquarters. This chapter discusses definitions, training strategy, prerequisite training, individual task training, and collective task training designed to prepare reconnaissance units at troop level and below for operations in urban terrain.

…

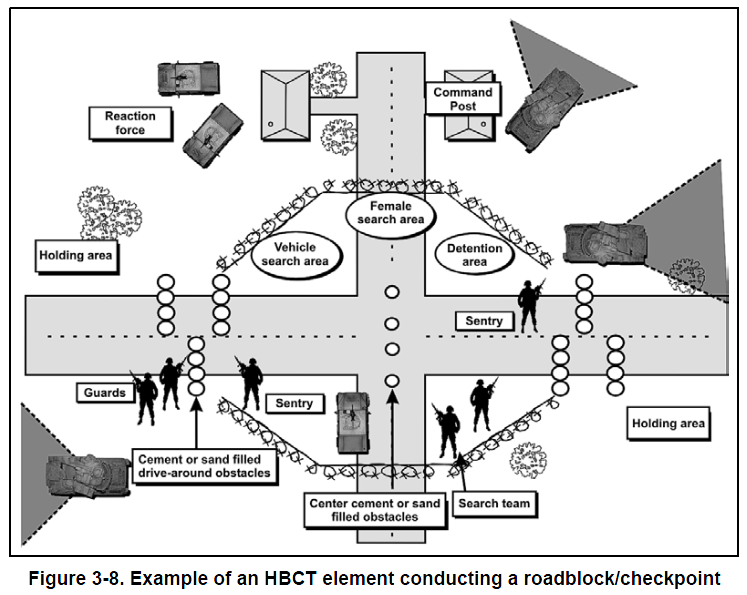

URBAN-SPECIFIC TASKS FOR STABILITY OPERATIONS AND CIVIL SUPPORT OPERATIONS

1-25. The following sample tasks are listed in TC 7-98-1:

- Conduct cordon and search operations, including site exploitation (SE).

- Conduct roadblock/checkpoint operations.

- Conduct civil disturbance operations.

- Secure civilians during operations.

- Process detainees and enemy prisoners of war (EPW).

1-26. See FM 3-06.11 for a review of additional tasks related to stability operations and civil support operations. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Conduct area security, including presence patrols.

- Conduct convoy escort.

- Conduct route clearance operations.

…

SECTION IX – CONTROL CIVILIAN MOVEMENT/DISTURBANCE

3-60. The likelihood of civil disturbances during urban operations is high. Handled poorly, the reaction to a civil disturbance can quickly escalate out of control, with potential long-term negative effects for mission accomplishment. Conversely, a well-handled situation will lead to an enhanced view of the reconnaissance platoon’s discipline and professionalism and potentially could result in fewer such incidents in the future.

SUPPORTING TASKS

3-61. Table 3-9 lists the supporting tasks that must be accomplished as part of controlling civilian movement and disturbances.

OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

3-62. A possible TTP description for this task is covered by procedures known by the acronym of IDAM:

- Isolate.

- Dominate.

- Maintain common situational awareness (SA).

- Employ multidimensional/multiecheloned actions.

3-63. The first step entails isolating, in time and space, the trouble spot from outside influence or interaction. Unit tactical operation centers in the theater must develop TTP that “isolate” riots or demonstrations to keep them from becoming larger and potentially more violent. The idea is to close access into and out of the demonstration location (Figure 3-13). Once access is closed, rioters tend to tire within hours, and the demonstration dies down, eventually resulting in a peaceful conclusion. Figure 3-14 provides a technique for positioning several tiers of checkpoints and tactical control points, given the mission to isolate a riot. Controlling major road networks into and out of the demonstration area also serves to enhance trafficability if the riot escalates.

3-64. Units dominate the situation through force presence and control of information resources. They can demonstrate an overwhelming show of force at command posts (CP) and dispatch helicopters to conduct overflights above demonstrations and massing civilian mobs. In addition, use of appropriate air assets can give commanders a bird’s-eye view of events, providing real-time updates on the situation and ensuring that units know the “ground truth” at all times. This knowledge gives commanders a decisive advantage both in negotiations with potentially hostile elements and in tactical maneuvers.

3-65. The following factors apply for the platoon in attempting to dominate the situation:

- Although units can dominate a civil disturbance using nonlethal munitions, it is important to consider force protection issues. In addition, if aviation assets are available, reconnaissance or utility helicopters can provide a show of force. Attack helicopters should be used in anoverwatch or reserve position.

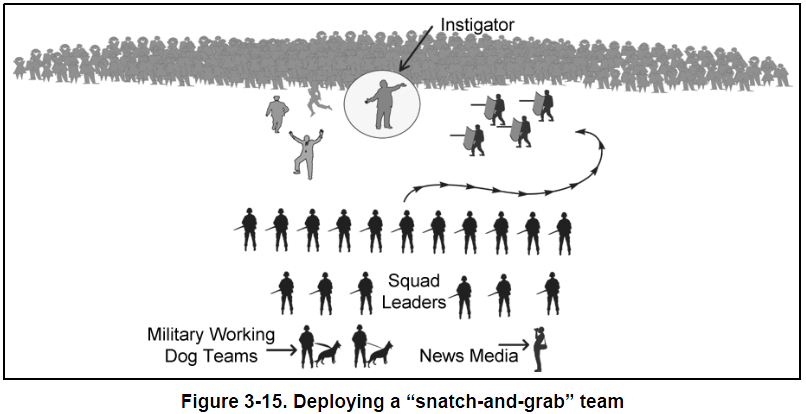

- Forces may need to detain group leaders or instigators to dominate a civil disturbance. An instigator is identified as a person who is “prodding” others to commit disruptive acts or who is orchestrating the group. Often, an instigator carries a bullhorn or hand-held radio.

- The smallest unit that can employ the “snatch-and-grab” technique is a platoon. Before a platoon deploys to quell a riot, identify a four-person snatch-and-grab team, two to secure the individual and two to provide security. It is imperative that each member of the snatch-and-grab team wears the Kevlar helmet with face shield and flak vest, but the team should not bring weapons or load-bearing equipment with them into the crowd. See Figure 3-15 for an illustration of the snatch-and-grab team.

- In accordance with Executive Order 11850, the President of the United States must approve the use of the riot control agency (RCA). The U.S. policy is to employ RCAs in limited circumstances, though never as a method of warfare. Commanders should be conscious that use of RCAs might pose a risk of escalation or public panic if it creates the erroneous perception that a chemical weapon is being used.

- Another element that is crucial for successful civil disturbance operations is the use of combat camera personnel. Document events to hold personnel, factions, and gangs or groups accountable. To ensure that the right message is being presented, control the information environment through the synchronized efforts of information engagement assets, with support from the staff judge advocate (SJA) and civil affairs (CA) offices.

3-66. Commanders and leaders maintain SA through timely, accurate, and complete multisource reporting. They can receive reports from a broad spectrum of sources. Unit CPs, air assets, and close liaison with HN police, NGOs, PVOs, and other civilian agencies all contribute to an accurate assessment of any situation. In addition, UAS, such as the Predator and Pioneer, are effective in observing large sectors of an AO. Analyze the reports produced and relay them to each unit involved in the operation.

3-67. As part of the IDAM procedures, multidimensional/multiechelon actions may entail the following considerations:

- Policy and legal considerations.

- ROE.

- Standards of conduct.

- High visibility of civil disturbance operations with the media, including leaders who must interact with the media.

- Crowd dynamics.

- Communication skills for leaders who must manage aggressive and violent behavior of individuals and crowds.

- Use of electronic warfare to monitor and control belligerent communications.

- Tactics.

- Lethal overwatch.

- Search and seizure techniques.

- Apprehension and detention.

- Neutralization of special threats.

- Recovery team tactics.

- Cordon operations to isolate potential areas of disturbance.

…

PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS

5-33. The smallest organizational PSYOP element is the tactical PSYOP team (TPT), consisting of three Soldiers. In high-intensity conflict, the TPT normally provides PSYOP support to a squadron. During counterinsurgency (COIN) and stability operations, planning and execution are primarily conducted at the troop level because the troop is the element that most often directly engages the local government, populace, and adversary groups. Operating in the troop AO allows TPTs to develop rapport with the target audience. This rapport is critical to the accomplishment of the troop’s mission. The TPT chief, usually a SSG or SGT, is the PSYOP planner for the troop commander. He also coordinates with the tactical PSYOP detachment (TPD) at the squadron level for additional support to meet the troop commander’s requirements. PSYOP planning considerations include the following:

- The most effective methods for increasing acceptance of friendly forces in occupied territory.

- The most effective methods of undermining the will of the threat to resist.

- The impact of PSYOP on the civilian population, friendly government, and law enforcement agencies in the area.

- Clearly identified, specific PSYOP target group(s).

- Undermining the credibility of threat leadership and whether or not it will bring about the desired behavioral change.

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Black Knight

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Black Knight

Monty Python Holy Grail

http://www.amazon.com/Monty-Python-Trinity-Pythons-Meaning/dp/B001E12ZAM/ref=…

TMZ – Hilary Duff — Rich Girl Hair

Hilary Duff is definitely stinkin’ rich and has very nice hair… and one (male) member of the TMZ newsroom just so happens to be her exact hair doppelganger!

TOP-SECRET-U.S. Northern Command Title 10 Dual Status Commander Standard Operating Procedures

USNORTHCOM PUBLICATION 3-20 TITLE 10 SUPPORT TO DUAL STATUS COMMANDER LED JOINT TASK FORCE STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES

- 194 pages

- January 31, 2012

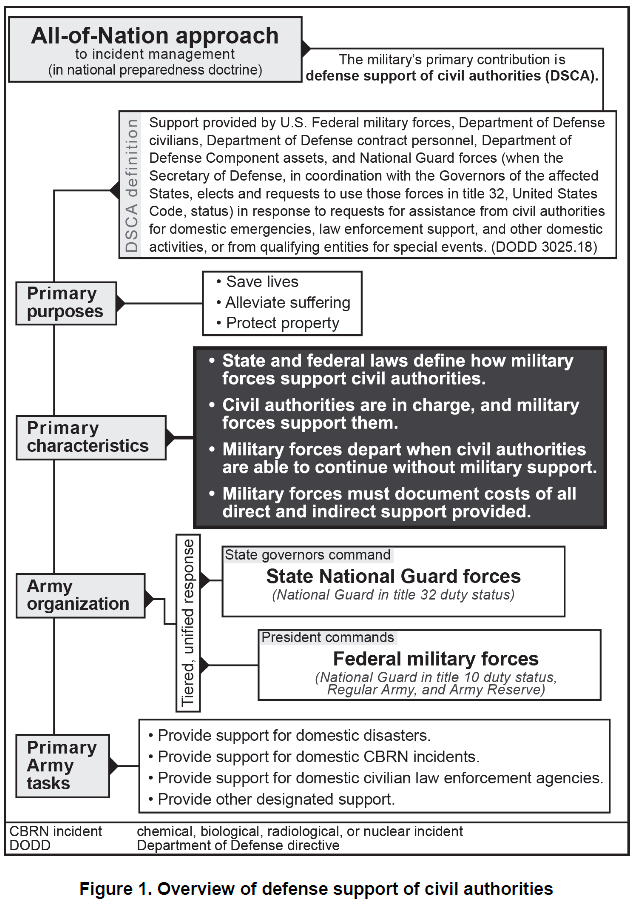

The Council of Governors and the President of the United States have identified the need for Dual Status Commanders (DSC) to unify the response efforts within the 54 Territories and States of the United States of America. United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) has identified Title 10 Deputy Commanders (O-6 in grade) to lead a Joint Support Force Staff Element (JSF-SE) that will integrate with the State-Level DSC staff in order to provide unity of effort to the response of both Title 32/State Active Duty (SAD) and Title 10 forces. This Standard Operating Procedures document outlines the USNORTHCOM Staff support to the DSC Program, a template for a T10 Deputy Commander Handbook and the methods, procedures and best practices for the JSF-SE.

…

This chapter provides an overview and background of the Dual Status Commander (DSC) program, and it provides an introduction to the Title 10 Support to Dual-Status Commander Led Joint Task Force Standard Operating Procedures which details the roles, responsibilities and processes/procedures for USNORTHCOM Staff, components, subordinates, and assigned/attached forces in supporting the DSC program.

1.1 Purpose

1.1.1. This standard operating procedure (SOP) outlines the Title 10 (T10) staff roles, responsibilities, and processes/procedures for support to a DSC during Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) operations (events/incidents requiring a Federal response).

1.1.2. This SOP consists of five chapters which provide: an overview of the DSC program (Chapter One); an outline of the roles, responsibilities, and processes/procedures for United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) Staff Support to DSC led Joint Task Forces (JTFs) (Chapter Two); T10 Deputy Commander (Chapter Three); the Joint Support Force Staff Element (JSF-SE) SOP (Chapter Four); and a recommended JSF-SE training curriculum (Chapter Five).

1.1.3. This SOP assumes that USNORTHCOM will provide a baseline JSF-SE that will integrate with the State JTF staff to support the T10 requirements. The JSF-SE will leverage support from the State JTF staff to meet the T10 requirements (e.g., reporting of JTF Situation Report (SITREP)/Storyboard, joint personnel status reports (JPERSTATs), logistical status reports (LOGSTATs), etc). While DSC led JTFs can organize with parallel and separate staff structures under a DSC, the best practice referenced within this SOP is the integrated staff model, where T10 staff are fully integrated with the State Active Duty/Title 32 (SAD/T32) staff.

1.1.4. All references to State within this SOP are used to refer to States, Territories, Commonwealths and the District of Columbia.

1.2 Background

1.2.1. In January 2009, the Secretary of Defense (SecDef) directed the development of options and protocols that allow Federal military forces supporting the Primary Agency to assist State emergency response personnel in a coordinated response to domestic disasters and emergency operations, while preserving the President’s authority as Commander in Chief.

1.2.2. In February 2010, during the first Council of Governors meeting, the SecDef acknowledged mutually exclusive sovereign responsibilities of Governors and the President, and urged all participants to focus on common ground and build a consensus approach to coordinate disaster response.

1.2.3. In August 2010, the Commander, United States Northern Command (CDRUSNORTHCOM) hosted an orientation visit for the initial State DSC candidates (i.e., Florida, California, and Texas).

1.2.4. In December 2010, a Joint Action Plan for DSC was approved by the Council of Governors, Department of Defense (DOD), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), stating that the appointment of a DSC is the “usual and customary command and control arrangement” when State and Federal military forces are employed simultaneously

in support of civil authorities in the United States.1.2.5. In May 2011, CDRUSNORTHCOM assigned USNORTHCOM/J36 Domestic Operations (NC/J36) as office of primary responsibility (OPR) for DSC. NC/J36 will coordinate with NORADUSNORTHCOM (N-NC) J5 and N-NC/J7 on doctrine and training, respectively.

1.2.6. This SOP is one of many documents which address the DSC integrated response to a DSCA event.

1.2.7. Figure 1-2 provides a hierarchy of DOD’s DSCA-related documents. Links to these references can be found in Annex A.

1.2.7.1. DOD Directive 3025.18 outlines the DOD roles in providing DSCA.

1.2.7.2. DOD Directive 5105.83 National Guard Joint Force Headquarters – State (NG JFHQs-State) establishes policy for and defines the organization and management, responsibilities and functions, relationships, and authorities of the NG JFHQs-State.

1.2.7.3. The Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) DSCA Standing Execution Order (EXORD) directs DSCA operations in support of the National Response Framework (NRF) and identified primary agencies in the USNORTHCOM and United States Pacific Command (USPACOM) domestic geographic areas of responsibility (AOR).

1.2.7.4. The CDRUSNORTHCOM Standing EXORD for DSCA operations outlines how USNORTHCOM will employ DOD forces in support of other federal agencies in the USNORTHCOM Operational Area (OA).

1.2.7.5. USNORTHCOM concept plan (CONPLAN) for DSCA is the Geographic Combatant Command (GCC) plan to support the employment of T10 forces providing DSCA in accordance with (IAW) the NRF, applicable federal laws, DOD Directives, and other policy guidance including those hazards defined by the National Planning Scenarios that are not addressed by other Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan tasked plans.

1.2.7.6. USNORTHCOM operations order (OPORD) 01-11/01-12 provides direction on the conduct of military operations within the USNORTHCOM AOR. USNORTHCOM produces an OPORD annually to address planned/forecasted military operations in support of the USNORTHCOM Theater Campaign Plan.

1.2.7.6.1. Subsequent Fragmentary Orders (FRAGOs) provide specific guidance (or changes to previous guidance) on unique events to address unforecasted military support operations.

1.2.7.7. The DSC Concept of Operations (CONOPS) describes the terms, responsibilities, and procedures governing the qualification, certification, appointment, and employment of a DSC for designated planned events, or in response to an emergency or major disaster within the United States, or its territories, possessions, and protectorates.

1.2.7.8. The USNORTHCOM Initial Entry Concept of Execution (CONEX) provides USNORTHCOM doctrine and procedures for establishing Joint initial command and control (C2) and support capability for its Civil Support (CS), Homeland Defense (HD) and Department of State (DOS) support operations.

1.2.7.9. The JTF Commander Training Course (JCTC) Handbook serves as a working reference and training tool for individuals who will command and employ JTFs for HD and CS at the federal and/or state level.

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Witch Village

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Witch Village

Monty Python Holy Grail

http://www.amazon.com/Monty-Python-Trinity-Pythons-Meaning/dp/B001E12ZAM/ref=…

Cryptome unveils – ATT Greenstar Secretly Spied Millions of Calls

ATT Project Greenstar Secretly Spied Millions of Calls

Greenstar prefigures current ATT’s once-secret participation in intercepting vast telecommunications data for the National Security Agency. More: https://www.eff.org/nsa-spying/faq

EXPLODING THE PHONE

The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell

PHIL LAPSLEY

Grove Press New York

[pp. 92-97]

If there were no billing records for fraudulent calls, there was no way to know how many fraudulent calls there were or how long they lasted. And that meant AT&T was gazing into the abyss. Say the phone company catches some college students with electronic boxes. Fantastic! But elation is soon replaced by worry. Is that all of them? Or is that just the tip of the iceberg? Are there another ten college students doing it? A hundred? Are there a thousand fraudulent calls a year or are there a million?

Engineers hate stuff like this.

Bell Labs, filled to the brim with engineers, proposed a crash program to build an electronic toll fraud surveillance system and deploy it throughout the network. It would keep a watchful eye over the traffic flowing from coast to coast, ever vigilant for suspicious calls — not every call, mind you, but a random sampling of a subset of them, enough to gather statistics. For the first time Bell Labs — and AT&T’s senior management — would have useful data about the extent of the electronic toll fraud problem. Then they’d be in a position to make billion-dollar decisions.

The project was approved; indeed, AT&T gave Bell Labs a blank check and told them to get right to work. Tippy-top secret, the program had the coolest of code names: Project Greenstar. Within Bell Labs Greenstar documents were stamped with a star outlined in green ink to highlight their importance and sensitivity. Perhaps as a joke, the project lead was given a military dress uniform hat with a green general’s star on it, an artifact that was passed on from one team lead to the next over the years.

Greenstar development began in 1962 and the first operational unit was installed at the end of 1964. Bill Caming, AT&T’s corporate attorney for privacy and fraud matters, became intimately familiar with the program. “We devised six experimental units which we placed at representative cities,” Caming said. “Two were placed in Los Angeles because of not only activity in that area, but also different signaling arrangements, and one was placed in Miami, two were originally placed in New York, one shortly thereafter moving to Newark, NJ, and one was placed in Detroit, and then about January 1967 moved to St. Louis.”

Ken Hopper, a longtime Bell Labs engineer involved in network security and fraud detection, recalls that the Greenstar units were big, bulky machines. “I heard the name ‘yellow submarine’ applied to one of them,” he says. They lived in locked rooms or behind fenced-in enclosures in telephone company switching buildings. A single Greenstar unit would be connected to a hundred outgoing long-distance trunk lines and could simultaneously monitor five of them for fraud. The particular long-distance trunk lines being monitored were selected at random as calls went out over them. At its core, Greenstar looked for the presence of 2,600 Hz on a trunk line when it shouldn’t be there. It could detect both black box and blue box fraud, since both cases were flagged by unusual 2,600 Hz signaling.

As Caming described it, “there were in each of these locations a hundred trunks selected out of a large number, and the [ … ] logic equipment would select a call. There were five temporary scanners which would pick up a call and look at it with this logic equipment and determine whether or not it had the proper [ … ] supervisory signals, whether, for example, there was return answer supervision. When we have a call, we have a supervisory signal that goes to and activates the billing equipment which usually we call return answer supervision. That starts the billing process and legitimizes the call, and if you find voice conversation without any return answer signal, and that is what it was looking for, it is an indication, a strong indication, of a possible black box that the caller called in; and if, for example, you heard the tell-tale blue box tone [ … ] this was a very strong indication of illegality because that tone has no normal presence upon our network at that point.”

When Greenstar detected something unusual, it took an audacious next step: it recorded the telephone call. With no warrant and with no warning to the people on the line, suspicious calls were silently preserved on spinning multitrack reel-to-reel magnetic tapes. If Greenstar judged it had found a black box call it recorded for sixty to ninety seconds; if it stumbled upon a blue box it recorded the entire telephone call. Separate tracks recorded the voice, supervisory signals, and time stamps.

When the tapes filled up they were removed by two plant supervisors. “They were the only two who had access from the local [telephone] company,” Caming says. Then they were sent via registered mail to New York City. There, at the Greenstar analysis bureau, specially trained operators — “long-term chief operators who had great loyalty to the system [who] were screened for being people of great trust,” Ken Hopper says — would listen to the tapes, their ears alert for indications of fraud. The operators would determine whether a particular call was illegal or was merely the result of an equipment malfunction or “talk off” — somebody whose voice just happened to hit 2,600 Hz and had caused a false alarm. When these operators were finished listening, the tapes would be bulk erased and sent back for reuse.

“The greatest caution was exercised,” Bill Caming recalls. “I was very concerned about it. The equipment itself was fenced in within the central office so that no one could get to it surreptitiously and extract anything of what we were doing. We took every pain to preserve the sanctity of the recordings.”

Project Greenstar went on for more than five and a half years. Between the end of 1964 and May 1970, Greenstar randomly monitored some 33 million U.S. long-distance phone calls, a number that was at once staggeringly large and yet still an infinitesimally tiny fraction of the total number of long-distance calls placed during those years. Of these 33 million calls, between 1.5 and 1.8 million were recorded and shipped to New York to be listened to by human ears. “We had to have statistics,” said Caming. Statistics they got: they found “at least 25,000 cases of known illegality” and projected that in 1966 they had “on the order of 350,000 [fraudulent] calls nationwide.”

“Boy, did it perk up some ears at 195 Broadway,” says Hopper. It wasn’t even that 350,000 fraudulent calls was that big a number. Rather, it was the fact that there was really nothing that could be . done about it, at least not at once. “It was immediately recognized that if such fraud could be committed with impunity, losses of staggering proportions would ensue,” Caming said. ”At that time we recognized — and we can say this more confidently in public in retrospect — that we had no immediate defense. This was a breakthrough almost equivalent to the advent of gunpowder, where the hordes of Genghis Khan faced problems of a new sort, or the advent of the cannon.”

The initial plan with Greenstar was simple: Wait. Watch. Listen. Gather statistics. Tell no one. Most important, don’t do anything that would give it away. “There was no prosecution during those first couple of years,” Hopper says. “It was so the bad guys would not be aware of the fact that they’re being measured.” It was only later, Hopper says. that AT&T decided to switch from measurement to prosecution. Even then! Hopper said, “The presence of Greenstar would not be divulged and that evidence gathered to support toll fraud prosecutions would be gathered by other means.” Instead, Hopper relates, Greenstar would be used to alert Bell security agents to possible fraud. The security agents would then use other means, such as taps and recordings, to get the evidence needed to convict. “Greenstar bird-dogging it would not be brought out,” says Hopper. “It was just simply a toll fraud investigation brought about by unusual signaling and you would not talk about the fact that there was a Greenstar device. That was the ground rule as I understood it. Any court testimony that I ever gave, I never talked about any of that.” As another telephone company official put it, “If it ever were necessary to reveal the existence of this equipment in order to prosecute a toll fraud case, [AT&T] would simply decline to prosecute.”

Bill Caming became AT&T’s attorney for privacy and fraud matters in September 1965. Greenstar had been in operation for about a year when he was briefed on it. His reaction was immediate: “Change the name. I don’t even know what it is, but it just sounds illegal. Change the name.” More innocent-sounding code names like “Dewdrop” and “Ducky” were apparently unavailable, so AT&T and Bell Labs opted for something utilitarian and unlikely to attract attention: Greenstar was rechristened “Toll Test Unit.”

As the new legal guy at AT&T headquarters, Caming faced questions that were both important and sensitive. Forget how it sounded, was Greenstar actually illegal? And if it was, what should be done about it? Before joining AT&T Caming had been a prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trials after World War II. He was highly regarded, considered by many to be a model of legal rectitude. Was there any way he could see that the AT&T program was legit?

There was. He later stated under oath that there was “no question” Greenstar was in fact legal under laws of the day — a surprising conclusion for what at first blush appears to be an astonishing overreach on the part of the telephone company. There were two parts to Caming’s reasoning. The first had to do with the odd wording of the wiretap laws of the early 1960s; using this wording Caming was able to thread a line of legal logic through the eye of a very specific needle to conclude that the program was legal under the law prior to 1968. The second part had to do with his position at American Telephone and Telegraph. In 1968, when Congress was considering new wiretapping legislation, Caming was in a position to help lawmakers draft the new law. He made very sure that the new wiretap act didn’t conflict with AT&T’s surveillance program.

Caming even informed the attorneys at the Justice Department’s Criminal Division about Greenstar in 1966 and 1967, in connection with some prosecutions. “Now, that does not say that they cleared it or gave me their imprimatur,” he allowed. But then, he added, “we did not feel we needed it.”

Years later, the Congressional Research Service agreed with Caming regarding the legality of the program — to a degree. While not going so far as to say there was “no question” that Greenstar was legal, it was concluded that “It is not certain that the telephone company violated any federal laws by the random monitoring of telephone conversations during the period from 1964 to 1970. This uncertainty exists because the Congressional intent [in the law] is not clear, and case law has not clearly explained the permissible scope of monitoring by the company.”

This whole mess formed a challenging business conundrum for AT&T executives, the sort of thing that would make for a good business school case study. Put yourself in their shoes. You have made an incredibly expensive investment in a product — the telephone network — that turns out to have some gaping security holes in it. You have, as Bill Caming said, no immediate defense against the problem. You finally have some statistics about how bad the problem is. It’s bad, but it’s not terrible, unless it spreads, in which case it’s catastrophic. Replacing the network will take years and cost a billion dollars or so. The Justice Department isn’t sure there are any federal laws on the books that actually apply. And every time you prosecute the fraudsters under state laws, not only do you look bad in the newspapers — witness the Milwaukee Journal’s 1963 front-page headline “Lonely Boy Devises Way of Placing Free Long Distance Calls” — but the resulting publicity makes the problem worse.

AT&T played the best game it could with a bad hand. For now it would quietly monitor the network, keeping a weather eye on the problem. When the company found college kids playing with the network, investigators would give them a stern talking — to and confiscate their colored boxes. Execs would start thinking about a slow, long-term upgrade to the network to eliminate the underlying problem. And if opportunity knocked and they could help out the feds with an organized crime prosecution — and in the process set a clear precedent for the applicability of the federal Fraud by Wire law — well, that would be lovely.

That opportunity came knocking in 1965. As it turned out used a sledgehammer.

[pp. 115-16]

On May 5, 1969, the Supreme Court declined to hear their case. More than three years after the FBI took a sledgehammer to Ken Hanna’s door, the issue was finally settled. If you were making illegal calls you had no right to privacy. The phone company could tap your line and turn the recordings over to law enforcement.

For the phone company, the victory was about much more than convicting Hanna or Dubis. AT&T now had a case that had gone all the way to the Supreme Court, one that proved, definitively, that 18 USC 1343 — the Fraud by Wire law that the Justice Department had believed wasn’t relevant — did apply to blue boxes. Thanks to Hanna’s failed appeal, the matter was now settled. AT&T finally had an arrow in its quiver to use against the fraudsters.

Throughout all of this legal drama one mystery remains: how had the telephone company found out about Hanna’s or Dubis’s blue box calls in the first place?

In the Hanna case, Miami telephone company security agent Jerry Doyle received a telephone call from the Internal Audit and Security Group at AT&T headquarters in New York asking him to investigate Hanna’s telephone line for a possible blue box. How did investigators in New York know that somebody in Miami was making illegal calls? Hanna’s attorneys asked Doyle this very question but Doyle said he didn’t know.

There was a one-word answer that nobody was giving: Greenstar. Hanna had been caught up in AT&T’s toll fraud surveillance network. Imagine what would have happened if this had come out during Hanna’s trial. After all, the Hanna case took almost four years to resolve and went to the Supreme Court based on tape recordings of each of his illegal calls. Think of the legal circus that would have ensued if Hanna’s defense attorneys had learned that the telephone company had been randomly monitoring millions of telephone calls nationwide and recording hundreds of thousands of them.

This added considerably to the stress of prosecuting Greenstar cases. AT&T attorney Caming recalls, “That was the problem in the Hanna case! Fortunately, defense counsel never probed too far as to what our original sources of information were.” With blue box prosecutions, he adds, “We were always on pins and needles as to what might spill over into the public press.”

Fortunately for AT&T in the Hanna and Bubis cases their luck held. And although Caming wasn’t a gambler or a bookmaker, he knew a thing or two about luck. In particular, he knew it didn’t last forever.

[p. 144]

At that point, the phone company billing records show something anomalous: here’s a call to a number, 555-1212, that should never look like it answered and yet it does. The phone company doesn’t like anomalies in its network, not so much because they think somebody might be messing with them, but just because anomalies probably mean that something is broken somewhere and needs repair.

“I knew that was an irregularity,” Acker says. “My fear was, you know, if this registers on your tape” — Acker knew the phone company in those days used paper tape for billing records — “they’ll be able to tell that [the call] answered, and they know it’s not supposed to.” Acker’s fears were right on the money. The phone company was indeed using computer-generated reports of supervision irregularities to spot blue boxes. Along with Greenstar, these reports were a primary tool the Bell System used to detect such fraud and, due to Greenstar’s secrecy, were among the most effective for prosecution.

Acker’s surprise caller was a security agent from his telephone company, New York Telephone. The agent had already talked to Acker’s friend John, likely because of 555-1212 supervision anomalies. But the reason the agent wanted to talk to Acker was more concrete. John had ratted out Acker to the security agent.

“He spilled his guts,” Acker says. “That was just an inconceivable no-no to me. That pretty much trashed our friendship. Forever and ever.” Forty years later you can still hear the intensity in Acker’s voice. “When you get in trouble, you don’t squeal on anybody.”

[p. 182]

Charlie Schulz and Ken Hopper, members of the technical staff of the Telephone Crime Lab at Bell Laboratories.

Hopper’s path to the Telephone Crime Lab was a circuitous one. In 1971 he was a distinguished-looking forty-five-year-old electrical engineer, a bit on the heavy side, with blue eyes, short brown hair, and glasses. Hopper had joined the Bell System some twenty-five years earlier, shortly after the end of World War II. Within a few years he had found himself at Bell Laboratories’ Special Systems Group working on government electronics projects. The stereotype of government work is that it’s boring, but Hopper was a lightning rod for geek adventure: wherever he went to do technical things physical danger never seemed far behind. There was the time he had to shoot a polar bear that had broken into his cabin while he was stationed up in the Arctic working on the then secret Distant Early Warning Line, the 1950s-era radar system that would provide advance warning of a Soviet bomber attack. Or the time he almost died in a cornfield in Iowa while building a giant radio antenna for a 55-kilowatt transmitter to “heat up the ionosphere” for another secret project. Then there’s the stuff he still can’t really talk about in detail, involving submarines and special tape recorders and undersea wiretaps of Soviet communications cables.

The Special Systems Group was a natural to help AT&T with the Greenstar toll-fraud surveillance network in the 1960s, Hopper says, and that work led to involvement with other telephone security matters. But the Telephone Crime Lab also owes its existence to the FBI. Hopper recalls, “In the mid-1960s the FBI laboratory came to our upper management and said they were getting electronic-involved crimes. They had no people in their laboratory that could examine evidence in these cases, especially related to communication systems, and they asked for Bell Labs’ assistance. Upper management of Bell Labs agreed that this was in the public interest and that we would do that. The work was assigned to my organization, Charlie Schulz being the supervisor. We had just a few people, never more than two or three, working on this stuff.

[pp. 304-05]

The Ashley-Gravitt affair was much in the newspapers that fall and attracted the attention of Louis Rose, an investigative reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Missouri’s preeminent newspaper. Rose had written a series of articles examining the apparently cozy relationship between Southwestern Bell and the Missouri Public Service Commission, its regulator in that state. “I had been looking at all the expenditures and all of the salaries and donations by Southwestern Bell,” Rose recalls. James Ashley, he says, “found a convenient thing in me, because I was already looking up these ties.”

In January 1975 the Texas scandal spread to North Carolina when a former Southern Bell vice president — another who had been forced out of the telephone company, as it happened — admitted during an interview that he had run a $12,000-a-year political kickback fund for the Bell System. The telephone company soon found itself being investigated by an assortment of agencies: the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Department of Justice, the Federal Wiretap Commission, the FCC, and the Texas attorney general.

The next shoe to drop in the scandal was, in a way, predictable, so predictable, in fact, that Bill Caming, AT&T’s patrician attorney for privacy and fraud matters, had predicted it ten years earlier. Caming couldn’t say exactly when it would happen, or exactly how it would happen, but he was sure it would happen. Ever since I965, when he had first learned about AT&T’s Greenstar toll-fraud surveillance system, with its tape recordings of millions of long-distance calls and its racks of monitoring equipment kept behind locked cages in telephone company central offices, Caming had maintained it was a matter of when — and not if — the news of Greenstar would eventually leak.

The “when” turned out to be February 2, 1975. The “how” was a front-page headline in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “Bell Secretly Monitored Millions of Toll Calls.” The article, by Louis Rose, quoted an anonymous source within the phone company and was chock-full of details: a list of the cities where Greenstar had been installed, the specifics of its operation, the stunning news that the phone company had monitored 30 million calls and tape-recorded some 1.5 million of them. Someone — someone high up, it seemed — had spilled the beans. By the next day the story had been picked up by the newswires and the New York Times.

Caming didn’t need a crystal ball to predict what happened next: a phone call from the chair of the House Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Administration of Justice. “He said. ‘I think we’re going to have to have one of your guys come down and explain all this to us,” Caming knew, as he had known for ten years now, that he would be the guy.

Less than three weeks later Caming found himself before the U.S. Congress. swearing to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Seated with Caming were Earl Conners, chief of security for Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, and John Mack, a Bell Labs engineer who was intimately familiar with the technical details of Greenstar. True to his reputation for loquaciousness (or maybe it was his legal training) Caming made sure his colleagues never got to speak more than two dozen words over the course of the three-hour hearing. Caming explained AT&T’s motivations for launching the surveillance system, how it operated, and, most important, why it was legal — indeed, not just legal, but in fact the only option AT&T had to combat blue box and black box fraud at the time. Never once did he refer to it as “Greenstar,” the name that ten years earlier he said “just sounds illegal.” Perhaps it was Caming’s legal reasoning, perhaps it was his appearance — competent, prepared, confident, yet self-effacing — or perhaps it was 195 Broadway’s deft handling of the press on the matter, but AT&T managed to weather the Greenstar storm without much damage. Despite some alarming headlines there was little fallout and no criminal investigation. The Greenstar matter quickly faded away.

[pp. 358-59]

Notes

95 “decline to prosecute”: Rose, “Bell Secretly Monitored Millions of Toll Calls.”

96 “Change the name”: During my interviews with Bill Caming I often used the term Greenstar in our discussions. Ever the AT&T attorney, he would periodically correct me: “No, that’s not its name. That was an internal code name that we stopped using.” Sometime later I visited the AT&T Archives in Warren, New Jersey, which maintains a computerized index of old Bell System files. I typed in “Greenstar” and watched the display light up like a Christmas tree as it found relevant documents. When I mentioned this to Caming a few days later, he gave a rueful laugh and responded, “Well, I guess you can’t keep a good name down.”

96 two parts to Caming’s reasoning: Before 1968, the federal wiretapping law was Section 605 of Title 18 of the United States Code. It was a strangely written law. As discussed in the next chapter, section 605 did not make wiretapping (“interception”) itself illegal. Rather, to commit a crime under 605 you had to both intercept a communication and then disclose the contents of the communication to someone else. Clearly when Greenstar recorded a call and a human listened to it, there was an interception, but because the trained operator listening to the tapes never discussed the contents of the communication (just the signaling of the call itself), there was no disclosure, and thus, AT&T asserted, no crime. In 1968 the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act became the new law that governed wiretapping — but that law had specific carve outs for random monitoring and interception of communications by telephone company personnel attempting to protect the assets of the telephone company.

96 “imprimatur”: Caming, “Surveillance,” pp. 243-44.

96 Congressional Research Service: Ibid., p. 234.

97 “Lonely Boy”: “Lonely Boy Devises Way of Placing Free Long Distance Calls.”

TMZ – Is ‘American Idol’ Racist!?

Nine black former contestants on “American Idol” are threatening to sue the show for being racist… and it led Harvey to go on one of his all-time CLASSIC rants about who he would fire in the TMZ newsroom!

SECRET – U.S. Northern Command-NORAD Battle Staff Standard Operating Procedures

NORAD AND USNORTHCOM PUBLICATION 1-01 BATTLE STAFF STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES

- 171 pages

- March 11, 2011

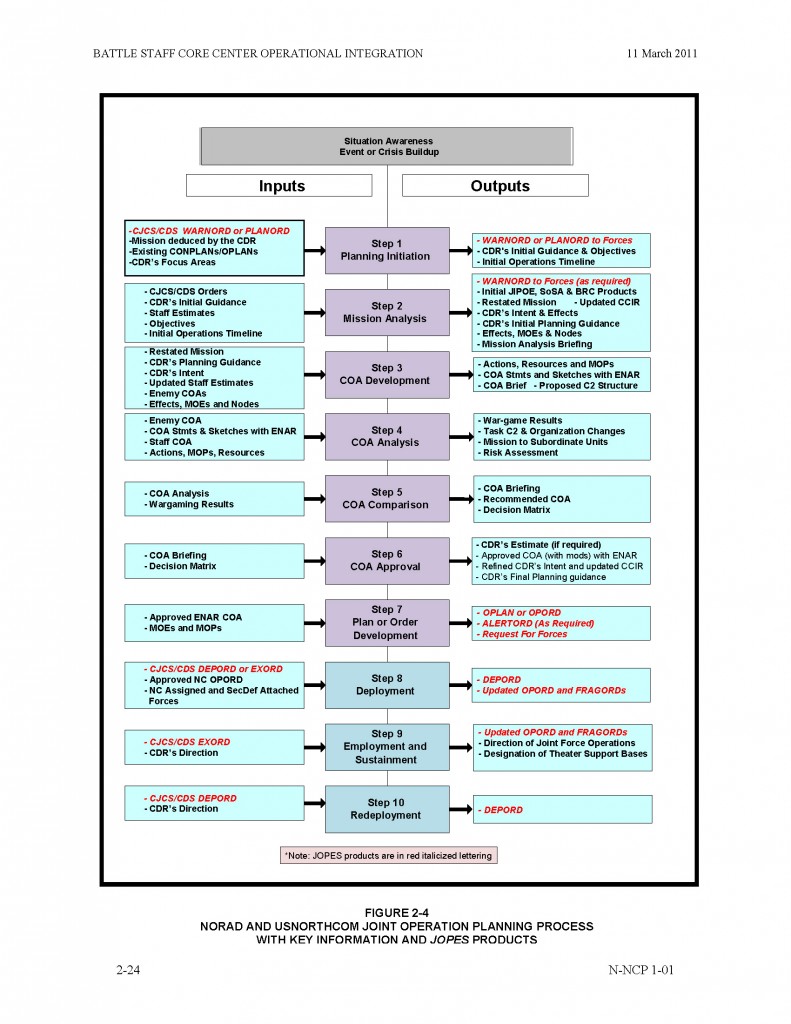

1.1.1 NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication Series

The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) Publication Series is the authoritative reference defining the Commands’ missions and structure, force employment objectives, mission area planning considerations and operational processes from the strategic to the tactical level. The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication Series also defines the Commands’ doctrine, as well as their operational tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP). The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication Series is authoritative because it defines the actions and methods implementing joint doctrine and describes how assigned and attached military forces will be employed in the Commands’ joint and combined operations. The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication Series consists of:

• Capstone publication: USNORTHCOM Publication (NCP) 1, Capstone Guidance

• Keystone publications:

− NCP 0-1, Homeland Defense Concept of Employment (HD CONEMP)

− NCP 0-2, Civil Support Concept of Employment (CS CONEMP)

− NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication (N-NCP) 1-01, Battle Staff Standard Operating Procedures (BSOP)

• Supporting publications: Supporting publications provide execution-level operational and tactical guidance, force employment direction and TTP. Supporting publications are called concepts of Execution (CONEX). These supporting publications can be functionally aligned (e.g., NCP 3-05 Joint Task Force Concept of Execution) or created by a subordinate unit (e.g., NCP 10-01, Joint Task Force North Concept of Execution), assigned component command headquarters (e.g., NCP 10-05, Army Forces North Concept of Execution) or supporting commander (e.g., NCP 10-08, United States Fleet Forces Command Concept of Execution in Support of USNORTHCOM)NORAD and USNORTHCOM Instruction (N-NCI) 10-154, NORAD and USNORTHCOM Publication Series provides further background on the Publication series policy and purpose.

1.1.2 NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff

The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff is activated during contingencies and crises to facilitate the Commander’s timely strategy and operational decision making. The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff task organizes using an adaptive joint headquarters construct, integrating J-code staff, special staff and agency liaisons into various Battle Staff nodes. This cross-functional Battle Staff organization ensures processes critical to the NORAD and USNORTHCOM missions are reliable, repeatable and efficient, and minimizes functional stove piping. The adaptive joint headquarters construct evolves beyond the traditional J-code staff organization thereby creating a Battle Staff organization optimized to execute cross-functional, joint war fighting processes to improve collaboration and increase understanding of the operational environment.

Though NORAD and USNORTHCOM are separate commands with different establishing authorities, they have complimentary missions. The two Commands share common values, understanding the urgency and significance of their duties in light of very real and present dangers. Operations and incidents could occur within the NORAD area of operations (AO) and USNORTHCOM area of responsibility (AOR) that would involve responses by both Commands. Canada and the United States also share a common border and have mutual defense and civil support and civil assistance interests. The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff organization and processes defined in this BSOP are intended to ensure the two Commands’ missions are accomplished effectively, efficiently and in close cooperation.

…

1.3 NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff Organization

Headquarters NORAD and Headquarters USNORTHCOM accomplishes its routine operations within the traditional J-code staff organizational structure and transitions to the NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff construct in response to preplanned events or contingencies as directed by the Commander. For preplanned events (contingency planning), the NORAD and USNORTHCOM Chief of Staff (N-NC/CS) will designate an OPR to stand up a joint planning team (JPT) or operations planning team (OPT). These teams can be led by any directorate, but are typically led by the Directorate of Strategy, Policy and Plans (N-NC/J5), NORAD Directorate of Operations (N/J3) or USNORTHCOM Directorate of Operations (NC/J3). The work of the JPT or OPT is conducted outside of the Battle Staff organization and processes, but may be transitioned to the Battle Staff’s crisis action planning (CAP) responsibility as the preplanned event approaches. The Battle Staff is designed to provide cross-functional expertise and leverage information technology to improve collaboration and decision superiority in CAP. The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff’s primary role is to support the Commander’s operational decision-making process during CAP and execution. The Battle Staff coordinates and collaborates with higher, adjacent, supporting, supported commands and agencies internal and external to the Department of Defense (DOD). This BSOP generally assumes Battle Staff activation will be required for a period between 12 hours and 30 days. However, such activation (Chapter 2) is scalable based on the nature and magnitude of the crisis or contingency.

The NORAD and USNORTHCOM Battle Staff is a three-tiered organization:

• The Command Executive Group (CEG), led by the Battle Staff Executive Director (N-NC/CS)

• Battle Staff Core Centers

− NORAD and USNORTHCOM Command Center (N2C2)

− NORAD Future Operations Center (N/FOC)

− USNORTHCOM Future Operations Center (NC/FOC)

− NORAD and USNORTHCOM Future Plans Center (FPC)

• Battle Staff supporting nodes (i.e., Centers, Cells, Boards and working groups [WG], as required)…

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Killer Rabbit

Monty Python – Holy Grail – Killer Rabbit

TMZ – Meet the ‘Plastic Wives!’

Hollywood’s so-called “Plastic Wives” aren’t just married to plastic surgeons… they’re also very proud (and VERY OBVIOUS) clients as well!

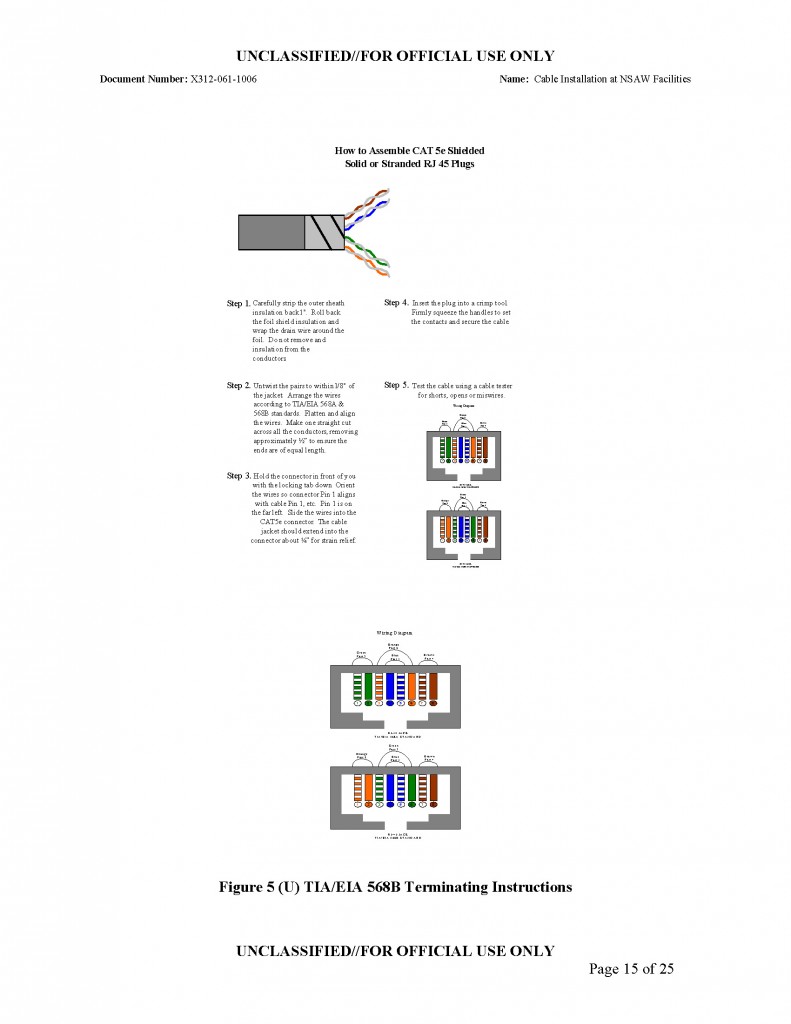

SECRET – NSA Technology Directorate Manual: Cable Installation at NSA Facilities

Cable Installation at NSAW Facilities

- Document Number: X312-061-1006

- Version 1.4

- 25 pages

- For Official Use Only

- September 25, 2008

(U//FOUO) This document provides detailed instructions for the implementation and installation of premise wire infrastructure in support of unclassified and classified networks within NSAW, Build-out Facilities, domestic facilities where NSA controls the plenum, domestic facilities where NSA does not control the plenum and all OCONUS field sites. This document provides instructions for implementations and installations of premise wiring in communications facilities, office spaces and machine rooms by ITD Internal Service Providers (ISP), External Service providers (ESP), field personnel stationed at the respective facilities or authorized NSA agents.

(U//FOUO) This document applies to all new voice, video, and data cabling including TS/SCI, Secret and Unclassified networks for all NSA facilities identified in the previous paragraph. This includes any construction, restoration, and modernization projects. This document is not intended to justify wholesale replacement and upgrade of existing premise wiring or cable infrastructure unless security violations are found.

(U//FOUO) It is presumed that any facility in which these instructions pertain is protected by approved means of anti-terrorist force protection (ATFP), owned or leased by the NSA/CSS and perimeters monitored by security cameras, intrusion alarms or other means approved and implemented by the Office of Physical Security, Countermeasures/Headquarters Security and Program Protection or Field Security. Where these do not apply, additional Security and TEMPEST counter measures are required. Details are provided in the respective sections of this document.

(U//FOUO) Prior to the installation of any Red communications or network infrastructure, all facilities will have Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF) accreditation in accordance with NSA/CSS Manual 130-1, Annex P and NSA/CSS Policy 6-3, Operational Information Systems Security Policy. All installation personnel must be legal U.S. citizens in accordance with NSA/CSS Policy 5-23, Physical Security Requirements for Controlled Areas.

(U//FOUO) Failure to adhere to the Standards outlined in this document will result in delays in activation and possibly denial of services until the facility is certified to be in compliance. Additional site surveys will be conducted by the Office of Technical Security Countermeasures as part of the automated Annex P process detailing appropriate Countermeasures for the respective facility.

…

Monty Python Holy Grail – French Taunter

Monty Python Holy Grail – French Taunter

Monty Python Holy Grail

http://www.amazon.com/Monty-Python-Trinity-Pythons-Meaning/dp/B001E12ZAM/ref=…

TMZ – Steven Tyler’s Speedo-Clad Bongo Bash!

Steven Tyler didn’t just rage his face off at a wild bongo bash on the beach in Hawaii… he did it while wearing a tiny mankini!

PI – National Counterintelligence Executive Specifications for Constructing Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND MANAGEMENT OF SENSITIVE COMPARTMENTED INFORMATION FACILITIES

- IC Tech Spec‐for ICD/ICS 705

- 166 pages

- April 23, 2012

This Intelligence Community (IC) Technical Specification sets forth the physical and technical security specifications and best practices for meeting standards of Intelligence Community Standard (ICS) 705-1 (Physical and Technical Standards for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities). When the technical specifications herein are applied to new construction and renovations of Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIFs), they shall satisfy the standards outlined in ICS 705-1 to enable uniform and reciprocal use across all IC elements and to assure information sharing to the greatest extent possible. This document is the implementing specification for Intelligence Community Directive (ICD) 705, Physical and Technical Security Standards for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (ICS-705-1) and Standards for Accreditation and Reciprocal Use of Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (ICS-705-2) and supersedes Director of Central Intelligence Directive (DCID) 6/9.

The specifications contained herein will facilitate the protection of Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) against compromising emanations, inadvertent observation and disclosure by unauthorized persons, and the detection of unauthorized entry.

…

A. Analytical Risk Management Process

1. The Accrediting Official (AO) and the Site Security Manager (SSM) should evaluate each proposed SCIF for threats, vulnerabilities, and assets to determine the most efficient countermeasures required for physical and technical security. In some cases, based upon that risk assessment, it may be determined that it is more practical or efficient to mitigate a standard. In other cases, it may be determined that additional security measures should be employed due to a significant risk factor.

2. Security begins when the initial requirement for a SCIF is known. To ensure the integrity of the construction and final accreditation, security plans should be coordinated with the AO before construction plans are designed, materials ordered, or contracts let.

a) Security standards shall apply to all proposed SCI facilities and shall be coordinated with the AO for guidance and approval. Location of facility construction and or fabrication does not exclude a facility from security standards and or review and approval by the AO. SCI facilities include but are not limited to fixed facilities, mobile platforms, prefabricated structures, containers, modular applications or other new or emerging applications and technologies that may meet performance standards for use in SCI facility construction.

b) Mitigations are verifiable, non-standard methods that shall be approved by the AO to effectively meet the physical/technical security protection level(s) of the standard. While most standards may be effectively mitigated via non-standard construction, additional security countermeasures and/or procedures, some standards are based upon tested and verified equipment (e.g., a combination lock meeting Federal Specification FF-L 2740A) chosen because of special attributes and could not be mitigated with non-tested equipment. The AO’s approval is documented to confirm that the mitigation is at least equal to the physical/technical security level of the standard.

c) Exceeding a standard, even when based upon risk, requires that a waiver be processed and approved in accordance with ICD 705.

3. The risk management process includes a critical evaluation of threats, vulnerability, and assets to determine the need and value of countermeasures. The process may include the following:

a) Threat Analysis. Assess the capabilities, intentions, and opportunity of an adversary to exploit or damage assets or information. Reference the threat information provided in the National Threat Identification and Prioritization Assessment (NTIPA) produced by the National Counterintelligence Executive (NCIX) for inside the U.S. and/or the Overseas Security Policy Board (OSPB), Security Environment Threat List (SETL) for outside the U.S. to determine technical threat to a location. When evaluating for TEMPEST, the Certified TEMPEST Technical Authorities (CTTA) shall use the National Security Agency Information Assurance (NSA IA) list as an additional resource for specific technical threat information. It is critical to identify other occupants of common and adjacent buildings. (However, do not attempt to collect information against U.S. persons in violation of Executive Order (EO) 12333.) In areas where there is a diplomatic presence of high and critical threat countries, additional countermeasures may be necessary.

b) Vulnerability Analysis. Assess the inherent susceptibility to attack of a procedure, facility, information system, equipment, or policy.

c) Probability Analysis. Assess the probability of an adverse action, incident, or attack occurring.

d) Consequence Analysis. Assess the consequences of such an action (expressed as a measure of loss, such as cost in dollars, resources, programmatic effect/mission impact, etc.).

Monty Python – Always Look On The Bright Side of Life – Filmclip

SECRECY NEWS – FORMER CIA OFFICER KIRIAKOU SENTENCED FOR LEAK

|

Monty Python – Hermit – Life of Brian

SI Swimsuit: Jessica Gomes – Body Painting Video

Jessica Gomes tells you about experience being a human canvas for the SI Swimsuit 2008 body painting shoot.

For more photos and videos visit http://www.si.com/swimsuit

SI Swimsuit: Jessica Gomes – Body Painting Video

NSA – ALAN GROSS CASE SPOTLIGHTS U.S. DEMOCRACY PROGRAMS IN CUBA

ALAN GROSS CASE SPOTLIGHTS U.S. DEMOCRACY PROGRAMS IN CUBALAWSUIT FILED BY FAMILY YIELDS DOCUMENTATION ON “OPERATIONAL” NATURE OF USAID EFFORTCONTRACTOR INTRODUCES CONFIDENTIAL RECORDS IN COURT ARGUMENTSNational Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 411Posted – January 24, 2013 Edited by Peter Kornbluh For more information contact: |

Related PostingsAmerican jailed in Cuba wants US to sign ‘non-belligerency pact’ to speed release Secrecy, politics at heart of Cuba project Cuba Proposes Exchange Deal for Imprisoned American, Alan Gross

|

Washington, D.C., January 18, 2013 – The U.S. government has “between five to seven different transition plans” for Cuba, and the USAID-sponsored “Democracy” program aimed at the Castro government is “an operational activity” that demands “continuous discretion,” according to documents filed in court this week, and posted today by the National Security Archive. The records were filed by Development Alternatives Inc (DAI), one of USAID’s largest contractors, in response to a lawsuit filed by the family of Alan Gross, who was arrested in Cuba in December 2009 for attempting to set up satellite communications networks on the island, as part of the USAID program.

In an August 2008 meeting toward the end of the George W. Bush administration, according to a confidential memorandum of conversation attached to DAI’s filing, officials from the “Cuba Democracy and Contingency Planning Program,” as the Democracy effort is officially known, told DAI representatives that “USAID is not telling Cubans how or why they need a democratic transition, but rather, the Agency wants to provide the technology and means for communicating the spark which could benefit the population.” The program, the officials stated, intended to “provide a base from which Cubans can ‘develop alternative visions of the future.'” Gross has spent three years of a 15-year sentence in prison in Cuba, charged and convicted of “acts against the integrity of the state” for attempting to supply members of Cuba’s Jewish community with Broadband Global Area Network (BGAN) satellite communications consoles and establish independent internet networks on the island. Last year, he and his wife, Judy, sued both DAI and USAID for failing to adequately prepare, train and supervise him given the dangerous nature of the democracy program activities. During a four-hour meeting last November 28, 2012, with Archive analyst Peter Kornbluh at the military hospital where he is incarcerated, Gross insisted that “my goals were not the same as the program that sent me.” He called on the Obama administration to meet Cuba at the negotiating table and resolve his case, among other bilateral issues between the two nations. The exhibits attached to DAI’s court filing included USAID’s original “Request for Proposals” for stepped up efforts to bring about political transition to Cuba, USAID communications with DAI, and Gross’s own proposals for bringing computers, cell phones, routers and BGAN systems-“Telco in a Bag,” as he called it-into Cuba. According to Kornbluh, DAI’s filing is “a form of ‘graymail'”–an alert to the U.S. government that unless the Obama administration steps up its efforts to get Gross released, the suit would yield unwelcome details of ongoing U.S. intervention in Cuba. In its effort to dismiss the suit, DAI’s filing stated that it was “deeply concerned that the development of the record in this case over the course of litigation [through discovery] could create significant risks to the U.S. government’s national security, foreign policy, and human rights interests.”

READ THE DOCUMENTSDocument l: USAID “Competitive Task Order Solicitation in Support of Cuba Democracy and Contingency Planning Program (CDCPP), May 8, 2008. Document 2: Memoranda of Conversation between USAID AND DAI officials, “Meeting Notes from USAID CDCPP Meeting, August 26, 2008. Document 3: Alan Gross, “Para La Isla,” Proposed Expansion of Scope of Work in Cuba Proposal, September 2009. Document 4: Declaration of John Henry McCarthy, DAI Global Practice Leader Document 5: Defendant Development Alternatives, Inc.’s Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Its Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Subject-Matter Jurisdiction and Failure to State a Claim, January 15, 2013. Document 6: Cuban Court Ruling Against Alan Gross, March 11, 2011, certified English translation. |

TMZ – Steven Tyler — I’ll Play the Bongo … You Watch My Dongo

See if you can watch this video of a mankini-sportin’ Steven Tyler bangin’ away in a drum circle in Maui … and NOT stare at his drumstick.

SECRET – National Counterintelligence Executive Specifications

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND MANAGEMENT OF SENSITIVE COMPARTMENTED INFORMATION FACILITIES

- IC Tech Spec‐for ICD/ICS 705

- 166 pages

- April 23, 2012

This Intelligence Community (IC) Technical Specification sets forth the physical and technical security specifications and best practices for meeting standards of Intelligence Community Standard (ICS) 705-1 (Physical and Technical Standards for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities). When the technical specifications herein are applied to new construction and renovations of Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIFs), they shall satisfy the standards outlined in ICS 705-1 to enable uniform and reciprocal use across all IC elements and to assure information sharing to the greatest extent possible. This document is the implementing specification for Intelligence Community Directive (ICD) 705, Physical and Technical Security Standards for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (ICS-705-1) and Standards for Accreditation and Reciprocal Use of Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (ICS-705-2) and supersedes Director of Central Intelligence Directive (DCID) 6/9.

The specifications contained herein will facilitate the protection of Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) against compromising emanations, inadvertent observation and disclosure by unauthorized persons, and the detection of unauthorized entry.

…

A. Analytical Risk Management Process

1. The Accrediting Official (AO) and the Site Security Manager (SSM) should evaluate each proposed SCIF for threats, vulnerabilities, and assets to determine the most efficient countermeasures required for physical and technical security. In some cases, based upon that risk assessment, it may be determined that it is more practical or efficient to mitigate a standard. In other cases, it may be determined that additional security measures should be employed due to a significant risk factor.

2. Security begins when the initial requirement for a SCIF is known. To ensure the integrity of the construction and final accreditation, security plans should be coordinated with the AO before construction plans are designed, materials ordered, or contracts let.

a) Security standards shall apply to all proposed SCI facilities and shall be coordinated with the AO for guidance and approval. Location of facility construction and or fabrication does not exclude a facility from security standards and or review and approval by the AO. SCI facilities include but are not limited to fixed facilities, mobile platforms, prefabricated structures, containers, modular applications or other new or emerging applications and technologies that may meet performance standards for use in SCI facility construction.

b) Mitigations are verifiable, non-standard methods that shall be approved by the AO to effectively meet the physical/technical security protection level(s) of the standard. While most standards may be effectively mitigated via non-standard construction, additional security countermeasures and/or procedures, some standards are based upon tested and verified equipment (e.g., a combination lock meeting Federal Specification FF-L 2740A) chosen because of special attributes and could not be mitigated with non-tested equipment. The AO’s approval is documented to confirm that the mitigation is at least equal to the physical/technical security level of the standard.

c) Exceeding a standard, even when based upon risk, requires that a waiver be processed and approved in accordance with ICD 705.

3. The risk management process includes a critical evaluation of threats, vulnerability, and assets to determine the need and value of countermeasures. The process may include the following:

a) Threat Analysis. Assess the capabilities, intentions, and opportunity of an adversary to exploit or damage assets or information. Reference the threat information provided in the National Threat Identification and Prioritization Assessment (NTIPA) produced by the National Counterintelligence Executive (NCIX) for inside the U.S. and/or the Overseas Security Policy Board (OSPB), Security Environment Threat List (SETL) for outside the U.S. to determine technical threat to a location. When evaluating for TEMPEST, the Certified TEMPEST Technical Authorities (CTTA) shall use the National Security Agency Information Assurance (NSA IA) list as an additional resource for specific technical threat information. It is critical to identify other occupants of common and adjacent buildings. (However, do not attempt to collect information against U.S. persons in violation of Executive Order (EO) 12333.) In areas where there is a diplomatic presence of high and critical threat countries, additional countermeasures may be necessary.

b) Vulnerability Analysis. Assess the inherent susceptibility to attack of a procedure, facility, information system, equipment, or policy.

c) Probability Analysis. Assess the probability of an adverse action, incident, or attack occurring.

d) Consequence Analysis. Assess the consequences of such an action (expressed as a measure of loss, such as cost in dollars, resources, programmatic effect/mission impact, etc.).

Monty Python – Biggus Dickus – Film – Life of Brian

Monty Python – Biggus Dickus – Film – Life of Brian

SI Swimsuit Video: Tori Praver Body Painting

Tori Praver tells you all about what it feels to become a human canvas in this SI Swimsuit 2008 bodypainting video.

For more SI Swimsuit photos and videos visit http://www.si.com/swimsuit.

The FBI – Former Chief Financial Officer of Stanford Group Entities Sentenced to Federal Prison

HOUSTON—James M. Davis, 64, formerly of Baldwyn, Mississippi, the former chief financial officer of Stanford International Bank (SIB) and Houston-based Stanford Financial Group, was sentenced today to five years in prison for his role in helping Robert Allen Stanford perpetrate a fraud scheme involving SIB and for conspiring to obstruct a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) investigation into SIB.

Today’s sentence was announced by U.S. Attorney Kenneth Magidson of the Southern District of Texas; Assistant Attorney General Lanny A. Breuer of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division; FBI Assistant Director Ronald T. Hosko of the Criminal Investigative Division; Assistant Secretary of Labor for the Employee Benefits Security Administration (DOL EBSA) Phyllis C. Borzi; Chief Postal Inspector Guy J. Cottrell of the U.S. Postal Inspection Service (USPIS); and Chief Richard Weber, of Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI).