Become a Patron!

True Information is the most valuable resource and we ask you to give back.

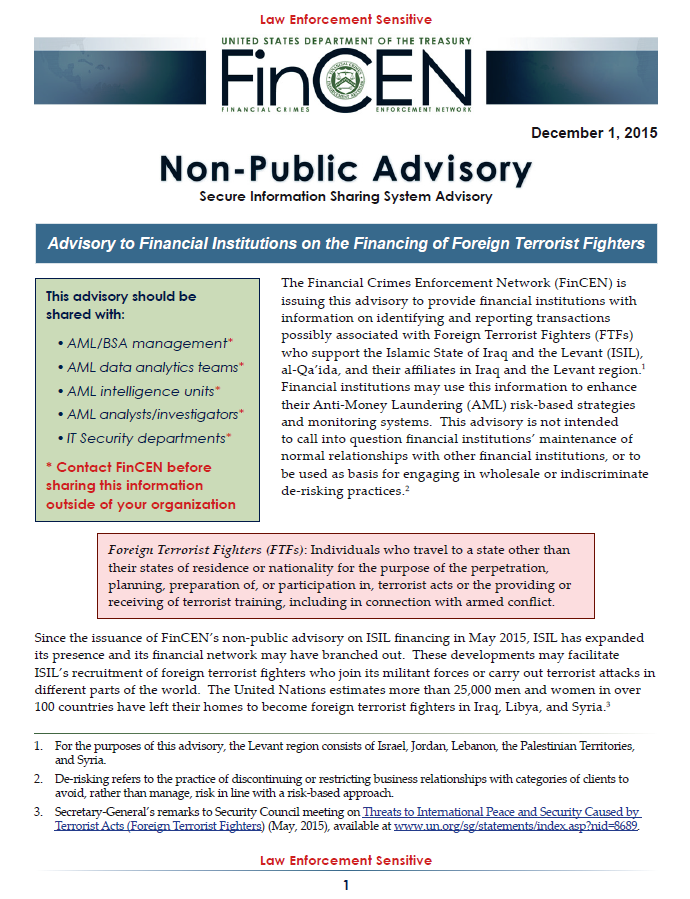

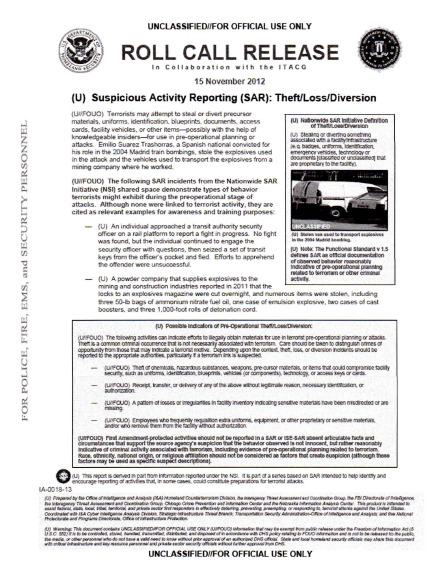

Advisory to Financial Institutions on the Financing of Foreign Terrorist Fighters

Page Count: 4 pages

Date: December 1, 2015

Restriction: Law Enforcement Sensitive

Originating Organization: Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

File Type: pdf

File Size: 357,074 bytes

File Hash (SHA-256):1675E6782F1526AD7E61B0D16459C2097E612BC9F8D30FC0F5252E65337BB97B

Download File

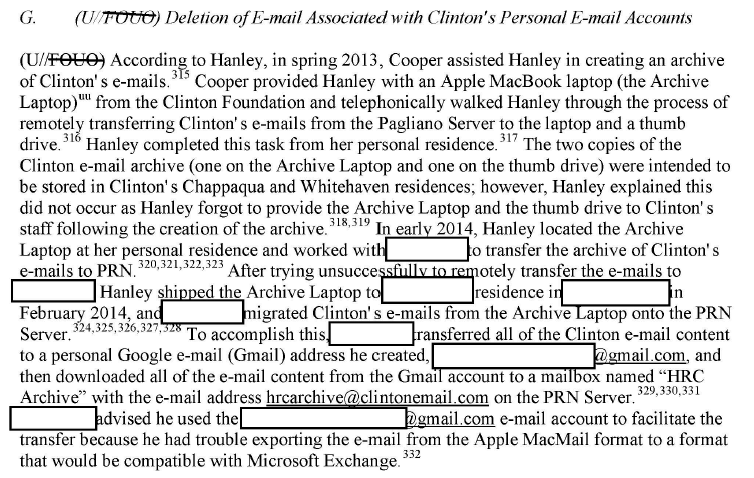

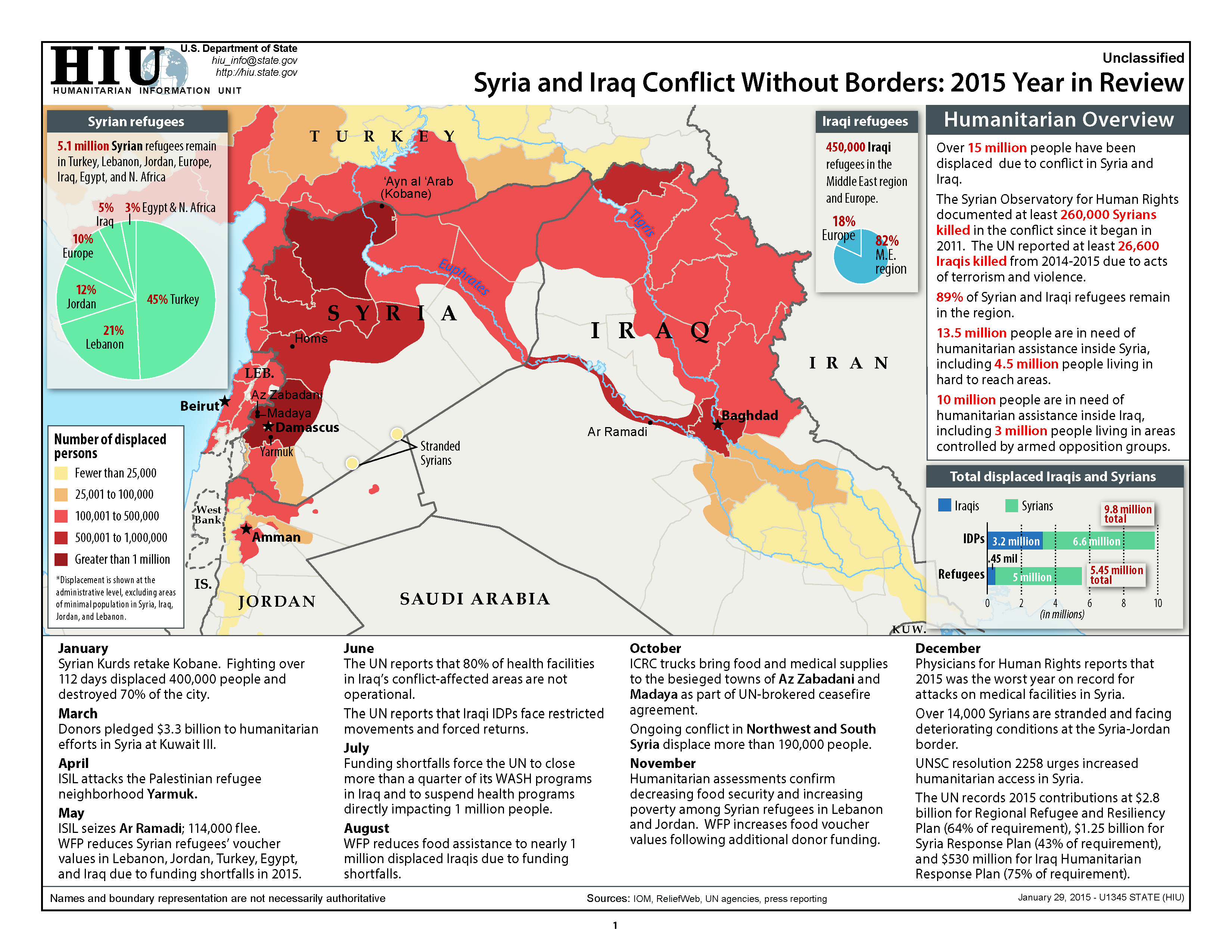

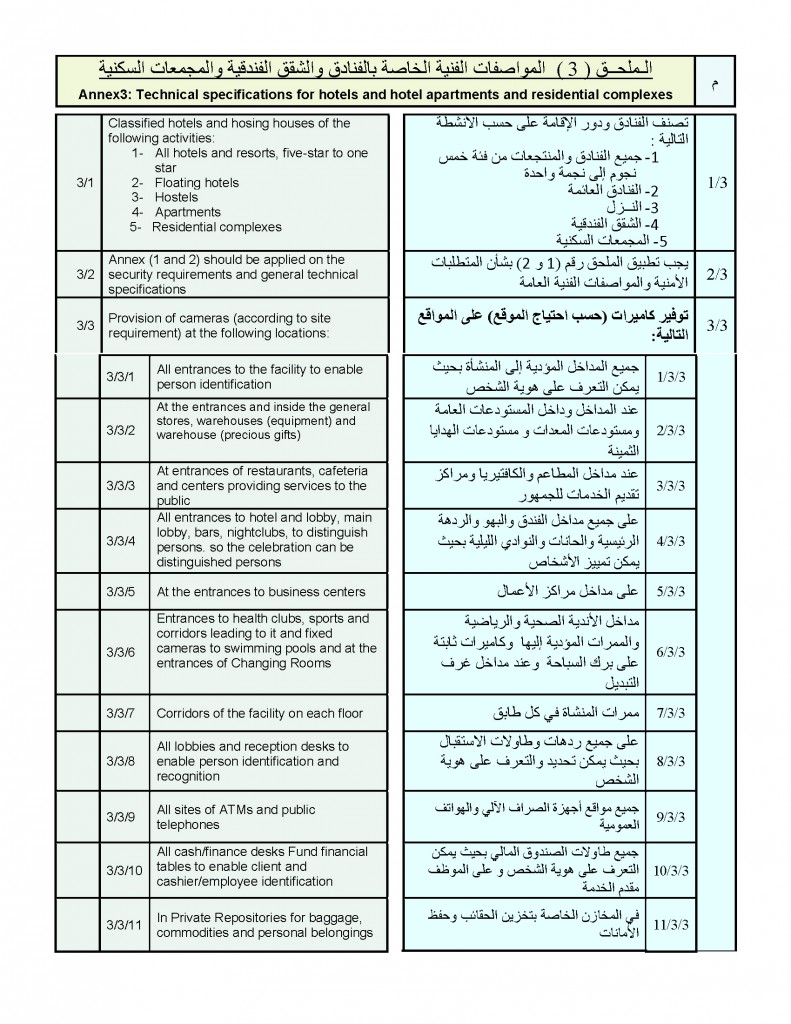

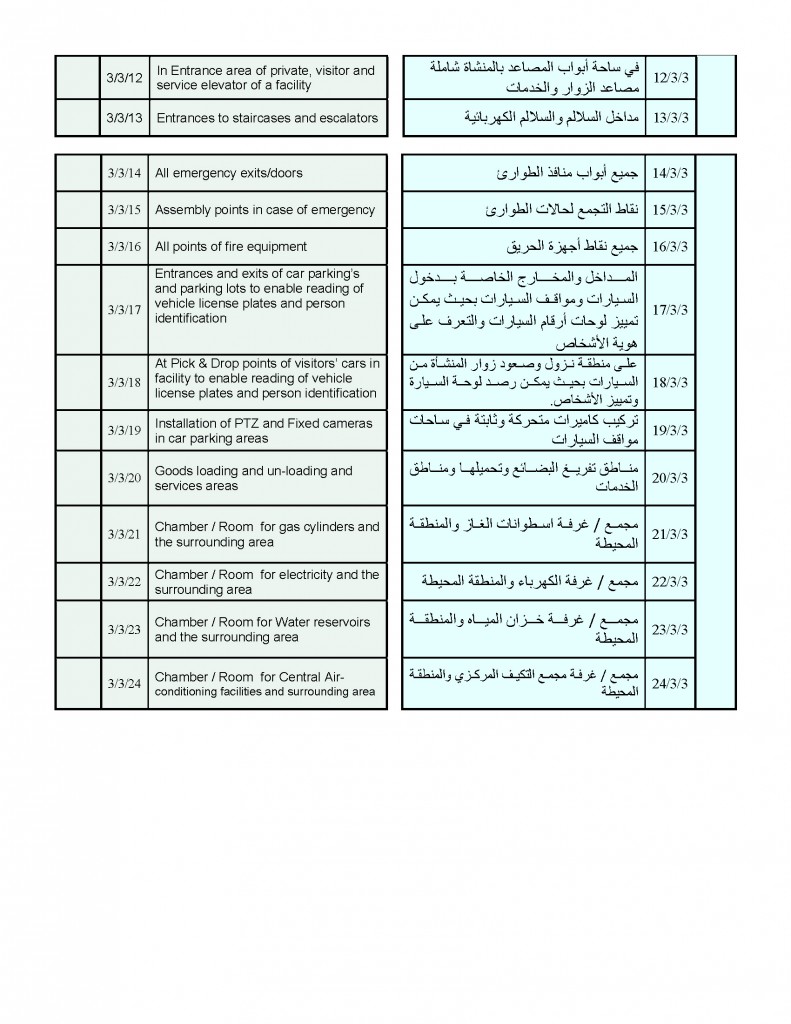

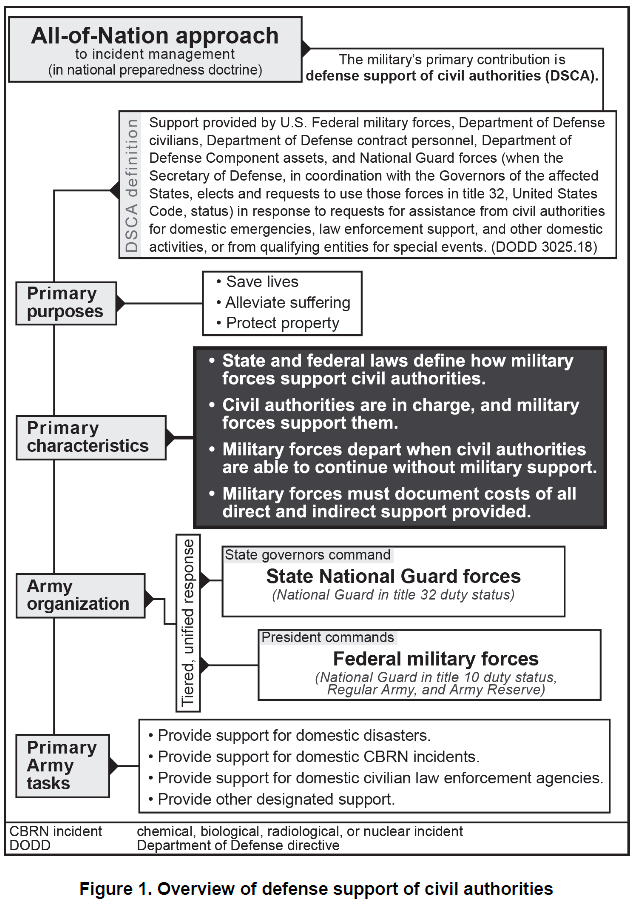

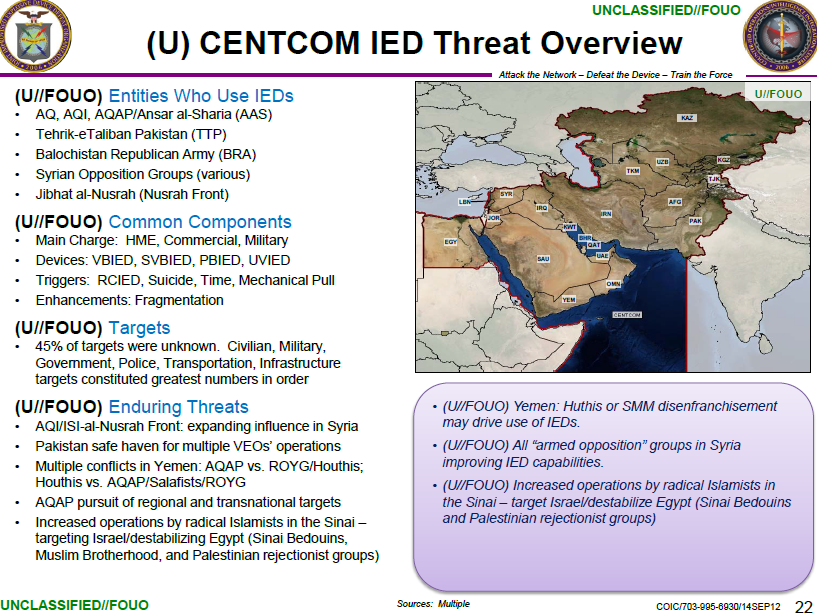

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is issuing this advisory to provide financial institutions with information on identifying and reporting transactions possibly associated with Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) who support the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), al-Qa’ida, and their affiliates in Iraq and the Lev ant region. Financial institutions may use this information to enhance their Anti-Money Laundering (AML) risk-based strategies and monitoring systems. This advisory is not intended to call into question financial institutions’ maintenance of normal relationships with other financial institutions, or to be used as basis for engaging in wholesale or indiscriminate de-risking practices.

…

Activity Possibly Associated With FTFs

Once recruited, FTFs seek to travel to areas where ISIL, al-Qa’ida, and their affiliates operate, such as Iraq and the Levant region. Accordingly, financial activity of FTFs may reflect transactions related to their travel preparations and arrangements, departure, in-transit period, and arrival and presence in the conflict zone.

FTFs may use diverse methods to disguise their finances or intentions. When determining whether transactions may be related to the financing of an FTF, financial institutions should consider multiple factors in addition to the red flags identified in the next section below, including:

• Deviation from a customer’s normal activity;

• Source of funds;

• Available information on the purpose of transactions;

• Publicly available information; and

• Whether a customer exhibits several of the red flags mentioned in this advisory and/or in FinCEN’s May 2015 non-public advisory on ISIL financing.

With respect to publicly available information, for instance, ISIL and other terrorist organizations are known to be active on social media sites. Financial institutions may find available social media information helpful in evaluating potential suspicious activity and in identifying risks connected to the red flags provided in this and other advisories. Similarly, the location from which a customer logs into a financial institution’s online services platform may also be considered when determining whether a transaction is suspicious (see next section).

…

In applying the red flags below, financial institutions are advised that no single transactional red flag is a clear indicator of terrorist activity. Financial institutions should consider additional factors, such as a customer’s overall financial activity and whether he or she exhibits multiple red flags, before determining a possible association to terrorist financing and FTFs. Financial institutions should also refer to the red flags and other information provided in this an d the May 2015 non-public advisory to formulate a more comprehensive assessment of potential suspicious activity.

Depending on their products and services offered, financial institutions may be able to observe one or more of the following red flags. Some of these red flags may be observed during general transactional screening, while others may be more readily identified during in-depth case reviews.

Activities Prior to Departure: Prospective FTFs make typical financial and logistical preparations prior to traveling. Transactions associated with FTFs may include:

Purchasing goods at camping or survival stores;

Purchasing first-person shooter games or engaging in combat training-type activities;

Purchase of airfare and payment of travel related fees (e.g., visa fees) involving countries in Europe or countries near or adjacent to ISIL-controlled areas—including Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey;

Establishing lines of credit and taking out personal loans where no loan repayments are made;

Liquidating personal assets, including retirement accounts/plans, and obtaining life insurance policies;

Receiving funds from or sending funds to seemingly unrelated individuals who are located near cities with a reported ISIL/al-Qa’ida-presence, where the transactions do not appear to have a lawful business purpose. These seemingly unrelated individuals may share common or similar addresses, telephone numbers, or other identifying information; and

Customers with minimal activity before ISIL’s expanded operations (early 2014) now showing inflows from unknown origins followed by fund transfers to beneficiaries (or ATM withdrawals) in Iraq, northeastern Lebanon, Libya, southern Turkey, or Syria.

Financing A Car, Financing A Used Car, Financing Definition, Financing Activities, Financing Calculator, Financing A Boat, Financing A Pool, Financing Land, Financing An Rv, Financing A Motorcycle, Financing A Car, Financing A Used Car, Financing Activities, Financing A Boat, Financing A Pool, Financing An Rv, Financing A Motorcycle, Financing Activities Include, Financing A Roof, Financing A Second Home, Financing Bedroom Sets, Financing Boats, Financing Braces, Financing Best Buy, Financing Business, Financing Breast Augmentation, Financing Building A House, Financing Bad Credit, Financing Banks, Financing Beds, Financing Calculator, Financing Contingency, Financing Calculator Car, Financing Car Lots, Financing Companies, Financing Central Air, Financing Car, Financing Cash Flow, Financing College, Financing Closing Costs, Financing Definition, Financing Dental Work, Financing Degree, Financing Dealerships Near Me, Financing Drones, Financing Dental Implants, Financing Decision, Financing Deals, Financing Development, Financing Define, Financing Engagement Rings, Financing Education In A Climate Of Change, Financing Electronics, Financing Examples, Financing Equipment, Financing Education, Financing Estimator, Financing Engine Repair, Financing Exotic Cars, Financing Expenses, Financing Furniture, Financing For Mobile Homes, Financing For Bad Credit, Financing For Auto Repair, Financing For Landscaping, Financing For Engagement Ring, Financing For Land, Financing For Manufactured Homes, Financing For Dental Work, Financing For Vacant Land, Financing Gap, Financing Graduate School, Financing Gaming Pc, Financing Golf Clubs, Financing Government, Financing Guns, Financing Golf Cart, Financing Gastric Sleeve, Financial Games, Financing Galaxy S8, Financing Hair, Financing Home Improvements, Financing Higher Education, Financing Home, Financing Home Depot, Financing Home Addition, Financing Health Care, Financing Hvac, Financing Hot Tub, Financing Honda, Financing Investment Property, Financing Ivf, Financing Intangible Capital, Financing In Spanish, Financial Icon, Financing Iphone 7, Financing Iphone, Financing Iphone 7 Plus, Financing Instruments, Financing Ikea, Financing Jewelry, Financing Jobs, Financing Job Description, Financing Jet Ski, Financing Jordans, Financing Jeep, Financing John Deere, Financing James Allen, Financing Jeep Grand Cherokee, Financing Job Salaries, Financing Kayak, Financing Kitchen Appliances, Financing Kia, Financing Kawasaki, Financing Ktm, Financing Kangen Water, Financing Kitchen Remodel, Financing Kitchen Cabinets, Financing Kay Jewelers, Financing Kubota Tractor, Financing Land, Financing Lease, Financing Laptop, Financing Law School, Financing Lawn Mower, Financing Lasik, Financing Loans, Financing Lift Kits, Financing Landscaping, Financing Loan Calculator, Financing Mobile Homes, Financing Meaning, Financing Macbook Pro, Financing Modular Homes, Financing Medical School, Financing Major, Financing Motorcycle, Financing Mba, Financing Motorcycle Calculator, Financing Mountain Bike, Financing New Construction, Financing No Credit Check, Financing New Car, Financing New Roof, Financing Near Me, Financing Needs, Financing New Ac Unit, Financing New Vs Used Car, Financing New Windows, Financing News, Financing Options, Financing Out Provision, Financing On Amazon, Financing Options For Cars, Financing On Used Cars, Financing Oac, Financing Options For Homes, Financing On Mobile Homes, Financing Options For A Business, Financing Operating Investing Activities, Financing Plastic Surgery, Financing Pool, Financing Payment Calculator, Financing Phones, Financing Plan, Financing Pole Barn, Financing Puppies, Financing Property, Financing Pharmacy School, Financing Pc, Financing Quotes, Financing Quizlet, Financing Questions, Financing Quads, Financing Quote Calculator, Financing Quantum, Financial Quiz, Financing Qualifications, Financing Questions And Answers, Financing Rims, Financing Rental Property, Financing Rv, Financing Rebuilt Title, Financing Rates, Financing Receivable, Financing Rolex, Financing Real Estate, Financing Renovations, Financing Roof, Financing Statement, Financing Solar Panels, Financing Salary, Financing Synonym, Financing Second Home, Financing Swimming Pool, Financing Section Of Cash Flow Statement, Financing Solutions, Financing Surgery, Financing Sources, Financing Tires, Financing The War, Financing Terms, Financing Tiny House, Financing Through Carmax, Financing Tv, Financing To Build A Home, Financing Through Apple, Financing Terrorism, Financing Through Dealership, Financing Used Car, Financing Used Boat, Financing Used Motorcycle, Financing Used Rv, Financing Utv, Financing Used Cars Near Me, Financing Usa, Financing Used Tractor, Financing Used Cars With Bad Credit, Financing Used Atv, Financing Vacant Land, Financing Vs Leasing, Financing Vs Leasing A Car, Financing Veneers, Financing Vacation, Financing Vehicle, Financing Vacation Home, Financing Vs Investing, Financing Vs Loan, Financing Vs Accounting, Financing With Bad Credit, Financing Wheels, Financing Washer And Dryer, Financing Wheels And Tires, Financing Weight Loss Surgery, Financing Ww2, Financing Wedding Rings, Financing Websites, Financing Windows, Financing With Apple, Financing Xbox One, Financing Xbox One Gamestop, Financing Xbox One Best Buy, Financing Xoticpc, Xidax Financing, Xiaomi Financing, Xidax Financing Review, Xerox Financing, Exim Financing, Xrimz Financing, Financing Your Business, Financing Your Mba, Financing Your Education, Financing Your Future, Financing Your Car, Financing Your First Home, Financing Your Small Business, Financing Your First Flip, Financing Your Home, Financing Your Wedding, Financing Zero Turn Mower, Financing Zales, Zero Financing Cars, Zibby Financing, Zero Financing, Zales Financing Credit Score, Zero Financing Cars Canada, Zero Financing Toyota, Ziegler Financing Corporation, Zzounds Financing, Isis Attack On Paris, Isis Attack In Us, Isis Attack Israel, Isis Attack In Syria, Isis Attack In France, Isis Attack In Philippines, Isis Attack 2017, Isis Attack In London, Isis Attack In Iran, Isis Attack In America, Isis Attack America, Isis Attack Afghanistan, Isis Attack April 2017, Isis Attack At Concert, Isis Attack Australia, Isis Attack Airport, Isis Attack Asia, Isis Attack Ariana Concert, Isis Attack Ariana, Isis Attack Articles, Isis Attack Brussels, Isis Attack Bangladesh, Isis Attack Britain, Isis Attack Base In Syria, Isis Attack Bus, Isis Attack By Pigs, Isis Attack By Boars, Isis Attack Baghdad, Isis Attack Bohol, Isis Attack Base, Isis Attack China, Isis Attack Church, Isis Attack Concert, Isis Attack Chicago, Isis Attack California, Isis Attack Cnn, Isis Attack Chemical, Isis Attack Catholic, Isis Attack Copenhagen, Isis Attack Churches In Egypt, Isis Attack Dubai, Isis Attack Dates, Isis Attack Drone, Isis Attack During Ramadan, Isis Attack Disney World, Isis Attack Dates 22nd, Isis Attack Dublin, Isis Attack Dates Pattern, Isis Attack Dates 22, Isis Attack Dates Uk, Isis Attack Egypt, Isis Attack Europe, Isis Attack Edc, Isis Attack England, Isis Attack Edinburgh 2016, Isis Attack Edc Las Vegas, Isis Attack Egypt Video, Isis Attack Egypt Palm Sunday, Isis Attack Egypt Church, Isis Attack Egypt Bus, Isis Attack France, Isis Attack Fresno, Isis Attack Fresno Ca, Isis Attack France 2016, Isis Attack Fox News, Isis Attack France 2015, Isis Attack France 2017, Isis Attack Footage, Isis Attack Florida, Isis Attack Facts, Isis Attack Germany, Isis Attack Garland Texas, Isis Attack Great Britain, Isis Attack Greece, Isis Attack Graphic, Isis Attack Glasgow, Isis Attack Geelong, Isis Attack Georgia, Isis Attack Guildford, Isis Attack Gaza, Isis Attack Helicopter, Isis Attack History, Isis Attack Hospital Kabul, Isis Attack Hotel, Isis Attack Hong Kong, Isis Attack Hama, Isis Attack Homs, Isis Attack Homes, Isis Attack Houston, Isis Attack Hastings, Isis Attack In Paris, Isis Attack In Us, Isis Attack Israel, Isis Attack In Syria, Isis Attack In France, Isis Attack In Philippines, Isis Attack In London, Isis Attack In Iran, Isis Attack In America, Isis Attack In Russia, Isis Attack Japan, Isis Attack Jordan, Isis Attack Jakarta, Isis Attack Jerusalem, Isis Attack July 4th, Isis Attack June 2015, Isis Attack July 4th 2015, Isis Attack January 2016, Isis Attack Jamaica, Isis Attack June 26, Isis Attack Kabul, Isis Attack Kuwait, Isis Attack Kirkuk, Isis Attack Kansas City, Isis Attack Kuala Lumpur, Isis Attack Kabul Hospital, Isis Attack Kaaba, Isis Attack Kenya, Isis Attack Kobani, Isis Attack Kitchener, Isis Attack List, Isis Attack Las Vegas, Isis Attack London, Isis Attack Locations, Isis Attack Liveleak, Isis Attack London 2017, Isis Attack Lebanon, Isis Attack Last Night, Isis Attack London 2015, Isis Attack Live, Isis Attack Map, Isis Attack Manchester, Isis Attack Marawi, Isis Attack May 2017, Isis Attack Military Base, Isis Attack Methods, Isis Attack Mosul, Isis Attack Malaysia, Isis Attack Mecca, Isis Attack Manila, Isis Attack News, Isis Attack New Orleans, Isis Attack New York, Isis Attack Nice France, Isis Attack Nice, Isis Attack North Korea, Isis Attack Northern Ireland, Isis Attack New Zealand, Isis Attack Next, Isis Attack Now, Isis Attack On Paris, Isis Attack On Us, Isis Attack On Israel, Isis Attack On France, Isis Attack On Russia, Isis Attack On Syria, Isis Attack On London, Isis Attack On Mosul, Isis Attack On Las Vegas, Isis Attack On Palm Sunday, Isis Attack Paris, Isis Attack Philippines, Isis Attack Palm Sunday, Isis Attack Pakistan, Isis Attack Pictures, Isis Attack Parliament, Isis Attack Pope, Isis Attack Paris 2017, Isis Attack Philippines 2017, Isis Attack Pattern, Isis Attack Queanbeyan, Isis Attack Qaraqosh, Isis Attack Quiapo, Isis Attack Queen, Isis Attack Qatar, Isis Attack Quebec, Isis Attack Quotes, Isis Attack Quaragosh Iraq, Isis Attack Al Qaeda, Isis Plan To Attack Queen, Isis Attack Russia, Isis Attack Recent, Isis Attack Russian Plane, Isis Attack Ramadan, Isis Attack Records, Isis Attack Refugee Camp, Isis Attack Resort World, Isis Attack Resorts World Manila, Isis Attack Rome, Isis Attack Russia 2017, Isis Attack Syria, Isis Attack Seattle, Isis Attack Saudi Arabia, Isis Attack Statistics, Isis Attack Spain, Isis Attack Sweden, Isis Attack Syrian Army, Isis Attack Strategy, Isis Attack St Petersburg, Isis Attack Syria 2017, Isis Attack Timeline, Isis Attack Texas, Isis Attack Today, Isis Attack Turkey, Isis Attack Today In Syria, Isis Attack This Morning, Isis Attack The Philippines, Isis Attack Tikrit, Isis Attack Today In Egypt, Isis Attack Techniques, Isis Attack Us, Isis Attack Usa, Isis Attack Uk, Isis Attack United States, Isis Attack Us Base, Isis Attack Usa 2017, Isis Attack Uae, Isis Attack Us Helicopter, Isis Attack Us Base In Syria, Isis Attack Uk 2017, Isis Attack Videos, Isis Attack Vegas, Isis Attack Vatican, Isis Attack Videos Liveleak, Isis Attack Vietnam, Isis Attack Venice, Isis Attack Virginia, Isis Attack Vancouver, Isis Attack Valparaiso, Isis Attack Vienna, Isis Attack Wiki, Isis Attack Westminster, Isis Attack Warning, Isis Attack World, Isis Attack Wicklow, Isis Attack Wigan, Isis Attack Washington, Isis Attack Wwe, Isis Attack Wolverhampton, Isis Attack Westfield, Isis Xmas Attack, Isis Attack Yesterday, Isis Attack Youtube, Isis Attack Yemen, Isis Attack Yazidi, Isis Attack Yyc, Isis Attack Yarmouk, Isis Attack Yarmouk Camp, Isis Attack Yorkshire, Isis Attack Ypg, Isis Attack Us, Isis Attack Zones, Isis Attack Zurich, Isis Attack New Zealand, Isis News, Isis Flag, Isis Thrown Off Cliff, Isis Goddess, Isis Definition, Isis Attack, Isis Uf, Isis Memes, Isis Map, Isis Website, Isis Attack, Isis Aspen, Isis And Osiris, Isis Archer, Isis Acronym, Isis Attacks In Us, Isis Asheville, Isis Antm, Isis Afghanistan, Isis Atrocities, Isis Band, Isis Bombing, Isis Build, Isis Beliefs, Isis Button, Isis Brown Sugar, Isis Books, Isis Being Killed, Isis Behind The Mask, Isis Best Gore, Isis Control Map, Isis Capital, Isis Chemical Weapons, Isis Caliphate, Isis Chan, Isis Cartoon, Isis Controlled Territory, Isis Candy Tomato, Isis Cnn, Isis Collection, Isis Definition, Isis Defeated, Isis Drones, Isis Documentary, Isis Death Toll, Isis Dead, Isis Deaths, Isis Daesh, Isis Drone Video, Isis Dc, Isis Egypt, Isis Explained, Isis Edc, Isis Europe, Isis Events, Isis Exhaust, Isis Enemies, Isis Excussion, Isis Exchange, Isis England, Isis Flag, Isis Fighters Killed, Isis Fighters Thrown Off Cliff, Isis Facts, Isis Fighters, Isis Fighters Executed, Isis Fails, Isis Funding, Isis Founder, Isis Flag For Sale, Isis Goddess, Isis Gallardo, Isis Goals, Isis Genocide, Isis Getting Shot, Isis Goat Meme, Isis Group, Isis Getting Bombed, Isis Goat, Isis Gif, Isis Harambe, Isis History, Isis Hair, Isis Hit List, Isis Heavy, Isis Hunting Permit, Isis Hostages, Isis Hunting, Isis Hand Sign, Isis Horus, Isis In Syria, Isis Iowa, Isis In The Philippines, Isis Iraq, Isis In Afghanistan, Isis In America, Isis Israel, Isis Ideology, Isis In Libya, Isis In Mosul, Isis Jokes, Isis Jhu, Isis Jv Team, Isis Jones, Isis Journal, Isis Jordan, Isis Jihad, Isis Japan, Isis John, Isis Joust Build, Isis King, Isis K, Isis Kids, Isis Kidnapping, Isis Knot, Isis Keyshia Wig, Isis Kurds, Isis Kneading, Isis Ksu, Isis King Engaged, Isis Leader, Isis Live Map, Isis Logo, Isis Leader Dead, Isis Location, Isis Las Vegas, Isis Losing, Isis Libya, Isis Lyrics, Isis Leadership, Isis Meaning, Isis Memes, Isis Map, Isis Mosul, Isis Magazine, Isis Music, Isis Members, Isis Mythology, Isis Marawi, Isis Music Hall, Isis News, Isis Name Meaning, Isis Name, Isis Numbers, Isis Net Worth, Isis News Mosul, Isis News Today, Isis National Anthem, Isis Nitric Acid Video, Isis New York, Isis Or Isil, Isis Origin, Isis Oasis, Isis Osiris, Isis Oil, Isis Oceanic, Isis Oracle, Isis On Twitter, Isis Osiris Horus, Isis Ohsu, Isis Propaganda, Isis Papers, Isis Pharmaceuticals, Isis Philippines, Isis Persona 5, Isis Pictures, Isis Phone Number, Isis Population, Isis Pizza, Isis Paris Attack, Isis Quotes, Isis Queen, Isis Quizlet, Isis Quran, Isis Questions, Isis Quartz, Isis Qaraqosh, Isis Quick Facts, Isis Qatar, Isis Quotes To America, Isis Religion, Isis Recruitment, Isis Recruitment Video, Isis Raqqa, Isis Romero, Isis Rea Boykin, Isis Russia, Isis Ramadan, Isis Reddit, Isis Recent Attacks, Isis Stands For, Isis Syria, Isis Symbol, Isis Song, Isis Sunni, Isis Social Media, Isis Shotgun, Isis Soldiers, Isis Smite, Isis Stronghold, Isis Thrown Off Cliff, Isis Territory, Isis Thrown Off Building Video, Isis Twitter, Isis Tv Show, Isis Theme Song, Isis Terrorist Attacks, Isis Torture, Isis Terrorist, Isis The Goddess, Isis Uf, Isis Uiowa, Isis Unveiled, Isis Uark, Isis Update, Isis Uk, Isis Using Drones, Isis Us, Isis Uniforms, Isis Urban Dictionary, Isis Vs Isil, Isis Valverde, Isis Victims, Isis Vs Usa, Isis Vegas, Isis Vs Taliban, Isis Vasconcellos, Isis Vs Kkk, Isis Vehicles, Isis Violence, Isis Website, Isis Wiki, Isis Wigs, Isis War, Isis Wings, Isis Women, Isis Wallet, Isis Weapons, Isis Waswas, Isis Wenger, Isis X Clan, Isis Xinjiang, Isis Xl, Isis Xpad, Isis X Rite, Isis Xinjiang China, Isis Xenophobia, Isis Xbox, Isis Youtube, Isis Yemen, Isis Yazidi, Isis Yugioh, Isis Youtube Channel, Isis Young, Isis Youth, Isis Youtube Ads, Isis Year Founded, Isis Y Osiris, Isis Zionist Plot, Isis Zoo, Isis Zion, Isis Zodiac, Isis Zone Of Control, Isis Zakat, Isis Zerocensorship, Isis Zodiac Sign, Isis Zarai Sandoval, Isis Zims, Islamic State Of Iraq And Syria, Islamic State Definition, Islamic State Flag, Islamic State Map, Islamic State Of Iraq, Islamic State News, Islamic State Isis, Islamic State Territory, Islamic State Vs Isis, Islamic State Group, Islamic State Afghanistan, Islamic State Attacks, Islamic State And Isis, Islamic State Affiliates, Islamic State Allies, Islamic State Anthem, Islamic State Australia, Islamic State And Taliban, Islamic State Ap Style, Islamic State Al Qaeda, Islamic State Borders, Islamic State Burn 9 In Kirkuk, Islamic State Bangladesh, Islamic State Background, Islamic State Bombing, Islamic State Burns 4 Captives Alive, Islamic State Board, Islamic State Bbc, Islamic State Books, Islamic State Banner, Islamic State Caliphate, Islamic State Countries, Islamic State Capital, Islamic State Claims, Islamic State Currency, Islamic State Current Map, Islamic State China, Islamic State Chemical Weapons, Islamic State Controlled Territory, Islamic State Control, Islamic State Definition, Islamic State Documentary, Islamic State Daesh, Islamic State Death Toll, Islamic State Defeat, Islamic State Drones, Islamic State Dabiq, Islamic State Drowning Video, Islamic State Documentary 2016, Islamic State Dam Warning, Islamic State Executions, Islamic State Egypt, Islamic State Europe, Islamic State Economy, Islamic State Explained, Islamic State Execution Liveleak, Islamic State Extremists, Islamic State Enemies, Islamic State Education, Islamic State Eu4, Islamic State Flag, Islamic State Fighters, Islamic State Facebook, Islamic State Funding, Islamic State Flag For Sale, Islamic State Flag Meaning, Islamic State Flag Amazon, Islamic State Facts, Islamic State Foreign Fighters, Islamic State Founder, Islamic State Group, Islamic State Goals, Islamic State Government, Islamic State Genocide, Islamic State Gun Shows, Islamic State Growth, Islamic State Gif, Islamic State Group Isis, Islamic State Group Crisis In Seven Charts, Islamic State Group Threatens Iran, Islamic State History, Islamic State Hacking Division, Islamic State Heavy, Islamic State Hacking Division Hit List, Islamic State Health Service, Islamic State History Timeline, Islamic State Hierarchy, Islamic State Hackers, Islamic State Hits U.s.-led Base In Syria, Islamic State Headquarters, Islamic State Isis, Islamic State In Iraq And Syria, Islamic State In Iraq, Islamic State In Philippines, Islamic State In Afghanistan, Islamic State In Libya, Islamic State Ideology, Islamic State In Somalia, Islamic State In Egypt, Islamic State In Yemen, Islamic State Jihadology, Islamic State Journal, Islamic State Jihadists, Islamic State Join, Islamic State Jihad, Islamic State Jokes, Islamic State Jordan, Islamic State Jihadi, Islamic State Jihadist Group, Islamic State Jakarta, Islamic State Khorasan, Islamic State Kill List, Islamic State Kenya, Islamic State Killed, Islamic State Kill List Names, Islamic State Kabul, Islamic State Khawarij, Islamic State Kerala, Islamic State Kashmir, Islamic State Khalid Masood, Islamic State Leader, Islamic State Libya, Islamic State Location, Islamic State Leadership, Islamic State Logo, Islamic State Levant, Islamic State Leader Killed, Islamic State Laws, Islamic State List, Islamic State Losing Territory, Islamic State Map, Islamic State Militants, Islamic State Mosul, Islamic State Magazine, Islamic State Meaning, Islamic State Map 2017, Islamic State Media, Islamic State Members, Islamic State Militant Group, Islamic State Meme, Islamic State News, Islamic State Name, Islamic State Newspaper, Islamic State Nasheed, Islamic State Number Of Fighters, Islamic State Numbers, Islamic State National Anthem, Islamic State News Agency, Islamic State Networks In Turkey, Islamic State News Agency Amaq, Islamic State Of Iraq And Syria, Islamic State Of Iraq, Islamic State Of France, Islamic State Of Iran, Islamic State Of Iraq And Ash Sham, Islamic State Of America, Islamic State Or Isis, Islamic State Origin, Islamic State Of Pakistan, Islamic State Of Sweden, Islamic State Philippines, Islamic State Propaganda, Islamic State Population, Islamic State Passport, Islamic State Plot, Islamic State Police, Islamic State Provinces, Islamic State Pakistan, Islamic State Pdf, Islamic State Publications, Islamic State Quotes, Islamic State Quizlet, Islamic State Quiapo, Islamic State Quran, Islamic State Quora, Islamic State Qatar, Islamic State Queen, Islamic State Quiz, Islamic State Quaragosh, Islamic State Qalamoun, Islamic State Religion, Islamic State Raqqa, Islamic State Recruitment, Islamic State Reuters, Islamic State Rules, Islamic State Reddit, Islamic State Revenue, Islamic State Ramadan, Islamic State Research Paper, Islamic State Report, Islamic State Syria, Islamic State Symbol, Islamic State Sunni, Islamic State Saudi Arabia, Islamic State Social Media, Islamic State Sharia Law, Islamic State Song, Islamic State Somalia, Islamic State Soldiers, Islamic State Statistics, Islamic State Territory, Islamic State Twitter, Islamic State Territory 2017, Islamic State Terrorist, Islamic State Timeline, Islamic State Territory Map, Islamic State The Digital Caliphate, Islamic State Terrorist Attacks, Islamic State Tattoo, Islamic State Telegram, Islamic State University, Islamic State Update, Islamic State United States, Islamic State Ultimate Goal, Islamic State Use Of Social Media, Islamic State Uses Chemical Weapons, Islamic State Uk, Islamic State Us, Islamic State University Of Sunan Gunung Djati, Islamic State United Nations, Islamic State Vs Isis, Islamic State Videos, Islamic State Vs Taliban, Islamic State Vice, Islamic State Vs Islam, Islamic State Versus Isis, Islamic State Videos 2017, Islamic State Vs Muslim, Islamic State Vs Al Qaeda, Islamic State Videos Liveleak, Islamic State Wiki, Islamic State War, Islamic State West Africa, Islamic State Weapons, Islamic State Website, Islamic State What Is It, Islamic State Wilayat, Islamic State Wahhabism, Islamic State Wild Boars, Islamic State Washington Post, Islamic State Xinjiang, Islamic State Youtube, Islamic State Yemen, Islamic State Youtube Ad, Islamic State Yazidi Slaves, Islamic State Youtube Channel, Islamic State Youtube Video, Islamic State Yazidi, Islamic State Yarmouk, Islamic State Yahoo, Islamic State Ypg, Islamic State Zionist, Islamic State Zakat, Islamic State Zarqawi, Islamic State Zebra, Islamic State Zone-h, Islamic State Zero Hour, Islamic State New Zealand, Islamic State Free Zone, Islamic State Grey Zone, Islamic State In Zambia, Terror Jr, Terror Bird, Terror In Resonance, Terror Dactyl, Terror Reid, Terror Squad, Terror Management Theory, Terror Attack, Terror Bird Kibble, Terror Definition, Terror Attack, Terror Attacks In Poland, Terror Attack London, Terror Attacks In The Us, Terror Attacks In Europe, Terror At Bottle Creek, Terror Attack Today, Terror Attacks 2017, Terror Attacks In France, Terror Alert, Terror Bird, Terror Bird Kibble, Terror Bird Ark, Terror Band, Terror By Night, Terror Behind The Walls, Terror Bird Saddle, Terror Bird Taming, Terror Bombing, Terror Band Merch, Tarot Cards, Terror Crossword Clue, Terror Couple Kill Colonel, Terror Creek Winery, Terror Cells, Terror Club Singapore, Terror Con, Terror Chokes, Terror Cave Vr, Terror Color Chart, Terror Dactyl, Terror Definition, Terror Dactyl Ride, Terror Dog, Terrordome, Terror Dogs Osrs, Terror Dactyl Travel Channel, Terror Documentary, Terrordrome, Terror Define, Terror Eyes, Terror Engine, Terror Exploit Kit, Terror En Lo Profundo, Terror Etymology, Terror En Chernobyl, Terror En Amityville, Terror Europe, Terror England, Terror Events, Terror Firmer, Terror Fabulous, Terror Famine, Terror From The Deep, Terror From The Year 5000, Terror Fabulous Action, Terror From Below, Terror From Beyond, Terror Face, Terror Fastpitch, Terror Groups, Terror Gif, Terror Groups In Africa, Terror Gloves, Terror Games, Terror Groups In Syria, Terror Gang Lyrics, Terror Groups In Afghanistan, Terror Groups In Middle East, Terror Germany, Terror Hardcore, Terror Hoard Pack, Terror House, Terror Hard Lessons, Terror Jr, Terror Hoodie, Terror Hc, Terror In Resonance, Terror Infinity, Terror In Tokyo, Terror In Europe, Terror In London, Terror In The Aisles, Terror In The Mind Of God, Terror In Meeple City, Terror In Spanish, Terror In The Shadows, Terror Jr, Terror Jr Come First, Terror Jr Lisa, Terror Jr Caramel, Terror Jr Death Wish, Terror Jr 3 Strikes, Terror Jr City, Terror Jr Lyrics, Terror Jr Singer, Terror Jr Tour, Terror Keepers Of The Faith, Terror Kerav, Terror Kibble, Terror Knight Ffbe, Terror Knight, Terror Kill Em Off, Terror Keepers Of The Faith Hoodie, Terror Keepers Of The Faith Lyrics, Terror Kill Em Off Lyrics, Terror Knight Tactics Ogre, Terror Level, Terror London, Terror Lyrics, Terror Lake, Terror Live, Terror Lowest Of The Low, Terror Larva, Terror Live By The Code, Terror Lake Kodiak, Terror Lab, Terror Management Theory, Terror Movies, Terror Merch, Terror Meaning, Terror Mtg, Terror Man, Terror Movies 2016, Terror Mask, Terror Meme, Terror Monitor, Terror News, Terror No Resonance, Terror Night, Terror Nocturno, Terror No Love Lost Lyrics, Terror Noise Division, Terror New Album, Terror News Today, Terror Night Manga, Terror Networks Definition, Terror On The Airline, Terror Of Mechagodzilla, Terror Of Tiny Town, Terror On The Fox, Terror Of The Autons, Terror Of The Zygons, Terror Of Resonance, Terror Of Terror, Terror On Highway 59, Terror On The Beach, Terror Pigeon, Terror Planet, Terror Pictures, Terror Plot, Terror Profundo, Terror Pig, Terror Pigeon Bandcamp, Terror Perfected, Terror Philippines, Terror Paris, Terror Quotes, Terror Squad, Terror Queues, Terror Attack, Terror Squad Lean Back, Terror Squad Chain, Terror Squad Album, Terror Squad Movie, Terror Squad Take Me Home, Terror Quotes From The Quran, Terror Reid, Terror Reid Uppercuts Lyrics, Terror Reid Who Dat Lyrics, Terror Reid Who Dat, Terror Resonance, Terror Ride Lagoon, Terror Robespierre And The French Revolution, Terror Reid Wiki, Terror Reid Soundcloud, Terror Reid Uppercuts Download, Terror Squad, Terror Synonym, Terror Skink, Terror Squad Lean Back, Terror Squad Chain, Terror Squad Album, Terror Squad Movie, Terror Squad Take Me Home, Terror Statistics, Terror Squad Entertainment, Terror Train, Terror Threads, Terror Twins, Terror Town, Terror Time Again, Terror Toons, Terror Trooper, Terror The Walls Will Fall, Terror Twins Dc, Terror Tower, Terror Universal, Terror Unscramble, Terror Uk, Terror Usa, Terror Under The Water, Terror Us, Terror Under The Bridge, Terror Under Stalin, Terror Universal Tour, Terror Update, Terrorvision, Terror Vs Horror, Terror Videos, Terror Von Der Staatsmacht, Terror Vs Fear, Terror Vice, Terror Vision Records, Terror Victims, Terror Vs Terrorism, Terrorvision Movie, Terror Watch List, Terror Warning, Terror Within, Terror Walker, Terror Word Scramble, Terror Watt Tf2, Terror Watt, Terror Watch, Terror Walls Will Fall, Terror Wood, Terror X Crew, Terror X Crew Discography, Terror X Crew Download, Terror X Crew Lyrics, Terror X Crew \U03c7\u03c1\u03c5\u03c3\u03b7 \U03b1\u03c5\u03b3\u03b7, Terror X Black Scale, Terror Xinjiang, Terror Xbox 360, Terror Xbox One, Terror Xochimilco, Terror Youtube, Terror Years, Terror Year 5000, Terror Y Nada Mas, Terror Your Enemies Are Mine Lyrics, Terror Y Encajes Pelicula, Terror You’re Caught, Terror Your Enemies Are Mine, Terror You’re Caught Lyrics, Terror Your Verdict, Terror Zone, Terror Zord, Terror Zone Band, Terror Zip Up Hoodie, Terror Zygons, Terror Zone Invisibles, Terror Zone Series, Terror Z, Terror Zone Energy, Terror Zone Lyrics, Terrorism Definition, Terrorism In America, Terrorism Statistics, Terrorism News, Terrorism In Europe, Terrorism Meaning, Terrorism In The United States, Terrorism Facts, Terrorism In France, Terrorism Definition Fbi, Terrorism Articles, Terrorism Around The World, Terrorism And Homeland Security, Terrorism And Political Violence, Terrorism And Social Media, Terrorism Act, Terrorism And The Media, Terrorism And Religion, Terrorism Apush, Terrorism Alert Desk, Terrorism By Religion, Terrorism Before 9\/11, Terrorism Books, Terrorism By Country, Terrorism By Ideology, Terrorism By Race, Terrorism By Religion Statistics, Terrorism Background, Terrorism Before And After 9\/11, Terrorism Britain, Terrorism Current Events, Terrorism Causes, Terrorism Can Be Defined As, Terrorism Charges, Terrorism Coverage, Terrorism Cartoon, Terrorism Clipart, Terrorism Cnn, Terrorism Chart, Terrorism Conference 2017, Terrorism Definition, Terrorism Definition Fbi, Terrorism Def, Terrorism Deaths Per Year, Terrorism Database, Terrorism Defined, Terrorism Documentary, Terrorism Deaths In Us, Terrorism During Ramadan, Terrorism Definition Quizlet, Terrorism Examples, Terrorism Europe, Terrorism Essay, Terrorism Events, Terrorism Effects, Terrorism Etymology, Terrorism England, Terrorism Expert, Terrorism East Africa, Terrorism Explained, Terrorism Facts, Terrorism France, Terrorism Financing, Terrorism Fbi Definition, Terrorism Fbi, Terrorism Facts 2016, Terrorism Foreign Policy, Terrorism Fear, Terrorism Fox News, Terrorism From Above, Terrorist Groups, Terrorism Graph, Terrorism Germany, Terrorism Global Issue, Terrorism Greece, Terrorism Government Definition, Terrorism Globalization, Terrorism Great Britain, Terrorism Government, Terrorism Goal, Terrorism History, Terrorism Has No Religion, Terrorism Has Increased Job Opportunities In The, Terrorism Hotline, Terrorism Headlines, Terrorism Hot Spots, Terrorism Homeland Security, Terrorism How The West Can Win, Terrorism How To Respond, Terrorism Hate Crime, Terrorism In America, Terrorism In Europe, Terrorism In The United States, Terrorism In France, Terrorism In Russia, Terrorism In Africa, Terrorism In Japan, Terrorism In The Middle East, Terrorism In China, Terrorism In Italy, Terrorist Jokes, Terrorism Japan, Terrorism Journals, Terrorism Justified, Terrorism Jobs, Terrorism Jordan, Terrorism Justification, Terrorism Journal Articles, Terrorism June 2017, Terrorism Jihad And The Bible, Terrorism Knowledge Base, Terrorism Kenya, Terrorism Kkk, Terrorism Kidnapping And Hostage Taking, Terrorism Kyrgyzstan, Terrorism Kashmir, Terrorism Kidnapping, Terrorism Kuwait, Terrorist Keywords, Terrorism Quran, Terrorism London, Terrorism Legal Definition, Terrorism Liaison Officer, Terrorism Laws, Terrorism Lesson Plans, Terrorism List, Terrorism London 2017, Terrorism Law Definition, Terrorism Logo, Terrorism Levels, Terrorism Meaning, Terrorism Movies, Terrorism Map, Terrorist Meme, Terrorism Middle East, Terrorism Morocco, Terrorism Media, Terrorism Mental Illness, Terrorism Manchester, Terrorist Meaning, Terrorism News, Terrorism Nyc, Terrorism New York Times, Terrorism Now, Terrorism Nigeria, Terrorism Netherlands, Terrorism North Korea, Terrorism Norway, Terrorism Numbers, Terrorism Notes, Terrorism Origin, Terrorism On The Rise, Terrorism Over Time, Terrorism On Social Media, Terrorism On Us Soil, Terrorism On The Internet, Terrorism Original Definition, Terrorism Over The Years, Terrorism Objectives, Terrorism Online, Terrorism Prevention, Terrorism Political Cartoons, Terrorism Pictures, Terrorism Philippines, Terrorism Powerpoint, Terrorism Problems, Terrorism Psychology, Terrorism Policy, Terrorist Propaganda, Terrorism Prevention Act 2015, Terrorism Quotes, Terrorism Quizlet, Terrorism Questions, Terrorism Quiz, Terrorism Quran, Terrorism Qatar, Terrorism Quick Facts, Terrorism Quiz Questions, Terrorism Quotes Goodreads, Terrorism Qualifications, Terrorism Risk Insurance Act, Terrorism Refers To, Terrorism Research, Terrorism Research Paper, Terrorism Research Center, Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, Terrorism Rates, Terrorism Report, Terrorism Religion, Terrorism Russia, Terrorism Statistics, Terrorism Synonyms, Terrorism Statistics 2016, Terrorism Solutions, Terrorism Studies, Terrorism Statistics Us, Terrorism Since 9\/11, Terrorism Statistics 2017, Terrorism Sentence, Terrorism Spain, Terrorism Today, Terrorism Timeline, Terrorism Threat Levels, Terrorism Topics, Terrorism Task Force, Terrorism Types, Terrorism Threats, Terrorism Tracker, Terrorism Tactics, Terrorism Trends, Terrorism United States, Terrorism Uk, Terrorism Us Definition, Terrorism Us Code, Terrorism United Kingdom, Terrorism Un, Terrorism Unit, Terrorism Un Definition, Terrorism Us Statistics, Terrorism Us Law, Terrorism Video, Terrorism Vs War, Terrorism Vocabulary, Terrorism Vs Gun Violence, Terrorist Videos, Terrorism Victims, Terrorism Vs Freedom Fighter, Terrorism Violence, Terrorism Victims Fund, Terrorism Vs Extremism, Terrorism Wikipedia, Terrorism Worksheet, Terrorism Webquest, Terrorism Worldwide, Terrorism Webster, Terrorism War, Terrorist Watch List, Terrorism War And Bush, Terrorism Will Never End, Terrorism Warning, Terrorism Xinjiang, Terrorism Poll, Terrorism Xtc, Terrorism Xtc Lyrics, Xenophobia Terrorism, Xl Terrorism Insurance, Xkcd Terrorism, Xinjiang Terrorism, Xian Terrorism, Xinjiang Terrorism China, Terrorism Youtube, Terrorism Yesterday, Terrorism Yemen, Terrorist Yell, Terrorist Youtube, Terrorist Yelling Allahu Akbar, Terrorist Yee, Terrorist Your Game Is Through, Terrorist Yelling Allahu Akbar And Explodes, Terrorist Yahoo Answers, Terrorism Zimbabwe, Terrorism Zambia, Terrorism Zones Pool Re, Terrorism Zanzibar, Terrorism Zones Insurance, Terrorism Zeitgeist, Terrorism Zurich, Terrorism Zealots, Terrorism Zone C, Terrorism Zinn, Terrorist Attack, Terrorist Definition, Terrorist Groups, Terrorist Attack In London, Terrorist Attacks 2017, Terrorist Attacks In Europe, Terrorist Watch List, Terrorist Meme, Terrorist Organizations, Terrorist Jokes, Terrorist Attack, Terrorist Attack In London, Terrorist Attacks 2017, Terrorist Attacks In Europe, Terrorist Attack Today, Terrorist Attacks In The Us, Terrorist Attacks In France, Terrorist Attacks In Poland, Terrorist Attacks 2016, Terrorist Attack In Paris, Terrorist Bombing, Terrorist Bomb Prank, Terrorist Beard, Terrorist Blows Himself Up, Terrorist Bomb Prank Run, Terrorist Bloopers, Terrorist Bomber, Terrorist Bird, Terrorist Blown Up, Terrorist Beliefs, Terrorist Countries, Terrorist Cell, Terrorist Costume, Terrorist Cartoon, Terrorist Cs Go, Terrorist Cat, Terrorist Clipart, Terrorist Color Chart, Terrorist Caught, Terrorist Camps In America, Terrorist Definition, Terrorist Define, Terrorist Def, Terrorist Deaths In Us 2016, Terrorist Dog, Terrorist Deaths In Us, Terrorism Definition, Terrorist Drawing, Terrorism Database, Terrorist Documentary, Terrorist Events, Terrorist Emoji, Terrorist Executions, Terrorist Exclusion List, Terrorist England, Terrorist Explosion, Terrorist Etymology, Terrorism Europe, Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center, Terrorist Elmo, Terrorist Fist Jab, Terrorist Fails, Terrorist Financing, Terrorist Flags, Terrorism Facts, Terrorist Funny, Terrace Farming, Terrorist France, Terrorist Fist Bumps, Terrorist From Syria, Terrorist Groups, Terrorist Groups In Africa, Terrorist Groups In Syria, Terrorist Gif, Terrorist Groups In The Middle East, Terrorist Group Definition, Terrorist Games, Terrorist Group Names, Terrorist Groups In Afghanistan, Terrorist Groups In Iraq, Terrorist Hijacking, Terrorist Headscarf, Terrorist Hunting Permit, Terrorist Hunt, Terrorist House, Terrorist Hotline, Terrorist Hat, Terrorist Hunter, Terrorist Hunt Realistic, Terrorist Handbook, Terrorist In Dearborn Mi, Terrorist In Spanish, Terrorist In Dearborn, Terrorist Isis, Terrorist In America, Terrorist In London, Terrorism In Philippines, Terrorist Incidents 2017, Terrorist Incidents, Terrorist Incident Report, Terrorist Jokes, Terrorist Jail, Terrorist Jacket, Terrorist Jokes Reddit, Terrorist John, Terrorist Jihad, Terrorist Jokes Youtube, Terrorist Janesville, Terrorist Jordan, Terrorism Jobs, Terrorist Killed, Terrorist Kidnapping, Terrorist Killed By Us, Terrorist Killed By Sniper, Terrorist Key And Peele, Terrorist Killer, Terrorist Kill List, Terrorist Knife Attack, Terrorist Killed By Drone, Terrorist Killed Liveleak, Terrorist List, Terrorist Leaders, Terrorist London, Terrorist Louis, Terrorist Language, Terrorist List Usa, Terrorist List 2017, Terrorist Leader Killed, Terrorist Logo, Terrorist Lyrics, Terrorist Meme, Terrorist Movies, Terrorist Meaning, Terrorist Music, Terrorist Mask, Terrorist Motives, Terrorist Movies 2016, Terrorist Map, Terrorist Mugshot, Terrorist Manchester, Terrorist Names, Terrorist News, Terrorist Neckerchief, Terrorist Networks, Terrorist Names Snl, Terrorist Nations, Terrorist Nuclear Weapons, Terrorist Next Door, Terrorist Nuke, Terrorist Nicknames, Terrorist Organizations, Terrorist Outfit, Terrorist Of 911, Terrorist Organizations In Africa, Terrorist Or Freedom Fighter, Terrorist Organizations Around The World, Terrorist On A Hoverboard, Terrorist Organizations In The Us, Terrorist Organizations In Syria, Terrorist Outfit Gta 5, Terrorist Prank, Terrorist Puppet, Terrorist Propaganda, Terrorist Pictures, Terrorist Prison, Terrorist Philippines, Terrorist Prank Run, Terrorist Png, Terrorist Perfume, Terrorist Photos, Terrorist Quotes, Terrorist Quiz, Terrorist Quizlet, Terrorist Quantico, Terrorism Questions, Terrorist Quotes Cs Go, Terrorist Attack, Terrorist Quebec, Terrorism Quran Verses, Terrorist Qualities, Terrorist Recruitment, Terrorist Religion, Terrorist Ringtone, Terrorist Run Prank, Terrorist Recruitment Online, Terrorist Rights, Terrorist Rap, Terrorist Recognition Handbook, Terrorist Recruitment Tactics, Terrorist Rhymes, Terrorist Synonym, Terrorist Screening Database, Terrorist Scarf, Terrorist Song, Terrorist Screening Center, Terrorist Surveillance Program, Terrorist Symbols, Terrorist Shot In Head, Terrorist Simulator, Terrorist States, Terrorist Threats, Terrorist Threats Lyrics, Terrorist Training Camps In Michigan, Terrorist Tactics, Terrorist Training Camps, Terrorist Targets, Terrorist Travel Prevention Act Of 2015, Terrorist Threat Level Usa, Terrorist Town, Terrorist Tactics Generally Include, Terrorist Uk, Terrorist Using Social Media, Terrorist Us, Terrorist Uniform, Terrorist Use Of Drones, Terrorist Use Of The Internet, Terrorist Unit, Terrorist Use Of Chemical Weapons, Terrorist University & Armageddon Now, Terrorist Uk Attack, Terrorist Videos, Terrorist Van, Terrorist Vines, Terrorist Vs Freedom Fighter, Terrorist Ventriloquist, Terrorist Vehicles, Terrorist Video Game, Terrorist Victims, Terrorist Vs Serial Killer, Terrorist Violence, Terrorist Watch List, Terrorist Watch, Terrorist Weapons, Terrorist Websites, Terrorist Win, Terrorist Words, Terrorist War, Terrorist Warning, Terrorist Watch List Countries, Terrorist Wiki, Terrorist Youtube, Terrorist Yell, Terrorist Yemen, Terrorist Yee, Terrorist Yelling Allahu Akbar, Terrorist Your Game Is Through, Terrorist Yelling Allahu Akbar And Explodes, Terrorist Yahoo Answers, Terrorist Yelling Sound Effect, Terrorist Yesterday, Terrorist Ziggs, Terrorist Ziggs Twitch, Terrorist Zion Il, Terrorist Zarqawi, Terrorist Zones, Terrorist Zakir Musa, Terrorist Zilean, Terrorist Zvornik, Terrorist Zombies, Terrorist Ziggs Skin

Philibert Aspairt, considered by some the first cataphile, becomes lost while exploring the Parisian catacombs by candlelight. His body is found 11 years later.

Philibert Aspairt, considered by some the first cataphile, becomes lost while exploring the Parisian catacombs by candlelight. His body is found 11 years later. In Australia, Melbourne cave enthusiasts Doug, Sloth and Woody found the Cave Clan, and soon begin exploring storm drains and other man-made caves as well as natural ones. Over the next decade, the Cave Clan absorbs other, smaller draining groups.

In Australia, Melbourne cave enthusiasts Doug, Sloth and Woody found the Cave Clan, and soon begin exploring storm drains and other man-made caves as well as natural ones. Over the next decade, the Cave Clan absorbs other, smaller draining groups. In Australia, Doug publishes the first issue of Il Draino, the Cave Clan newsletter.

In Australia, Doug publishes the first issue of Il Draino, the Cave Clan newsletter. After finding a Cave Clan sticker in a drain under Sydney, Predator forms the group’s first official interstate branch, the

After finding a Cave Clan sticker in a drain under Sydney, Predator forms the group’s first official interstate branch, the  In the US, Dug Song and Greg Shewchuk publish the first issue of Samizdat, a zine featuring urban stunts involving tunnels and rooftops. They publish two issues before going on permanent hiatus.

In the US, Dug Song and Greg Shewchuk publish the first issue of Samizdat, a zine featuring urban stunts involving tunnels and rooftops. They publish two issues before going on permanent hiatus.

In the US, Max Action and his fellow University of Minnesota explorers form the group “Adventure Squad”, which they later rename Action Squad.

In the US, Max Action and his fellow University of Minnesota explorers form the group “Adventure Squad”, which they later rename Action Squad. Ninjalicious publishes the first issue of the paper zine Infiltration. In the editorial of the first issue, he coins the term “urban exploration” and introduces the idea of exploring off-limits areas of all types as a hobby.

Ninjalicious publishes the first issue of the paper zine Infiltration. In the editorial of the first issue, he coins the term “urban exploration” and introduces the idea of exploring off-limits areas of all types as a hobby. With the third issue of their magazine Jinx, long-time New York City explorers Lefty Leibowitz and L.B. Deyo begin featuring articles on urban mountaineering and exploration. Jinx goes online at planetjinx.com (later

With the third issue of their magazine Jinx, long-time New York City explorers Lefty Leibowitz and L.B. Deyo begin featuring articles on urban mountaineering and exploration. Jinx goes online at planetjinx.com (later

In Scotland, the Milk Grate Gang forms with the purpose of exploring the Glaswegian underworld, and places its adventures online at Subterranean Glasgow.

In Scotland, the Milk Grate Gang forms with the purpose of exploring the Glaswegian underworld, and places its adventures online at Subterranean Glasgow.

Julia Solis and her explorer friends stage an event called “Dark Passage” in the subway tunnels beneath New York City.

Julia Solis and her explorer friends stage an event called “Dark Passage” in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. Members of the Sydney Cave Clan publish the first issue of the zine Urbex. They publish three more issues on paper before switching to an electronic format.

Members of the Sydney Cave Clan publish the first issue of the zine Urbex. They publish three more issues on paper before switching to an electronic format.

Doug launches a full-colour publication called The Cave Clan Magazine and prints 100 copies of the premiere issue.

Doug launches a full-colour publication called The Cave Clan Magazine and prints 100 copies of the premiere issue.

Roughly 65 explorers from across North America and a couple from beyond converge on Toronto for a successful four-day exploration convention trickily-titled Office Products Expo 94.

Roughly 65 explorers from across North America and a couple from beyond converge on Toronto for a successful four-day exploration convention trickily-titled Office Products Expo 94.

You must be logged in to post a comment.