Become a Patron!

True Information is the most valuable resource and we ask you to give back.

The following report is part of a series produced by the TRADOC G-2 Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA). While the reports contain no control markings, they are not released publicly.

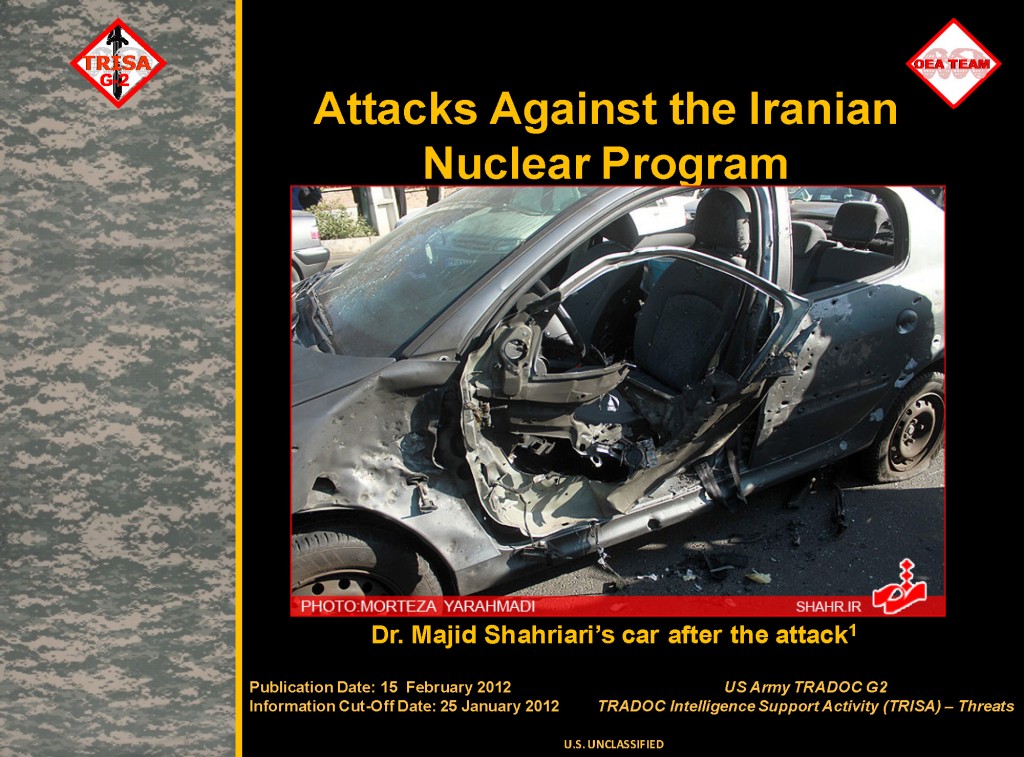

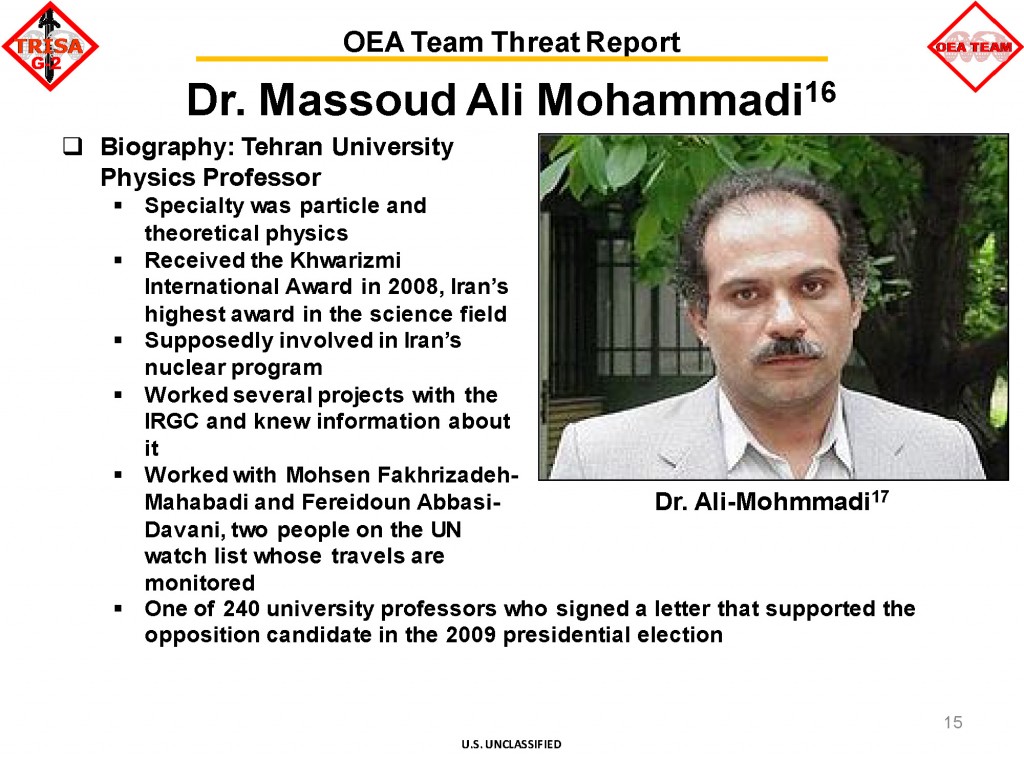

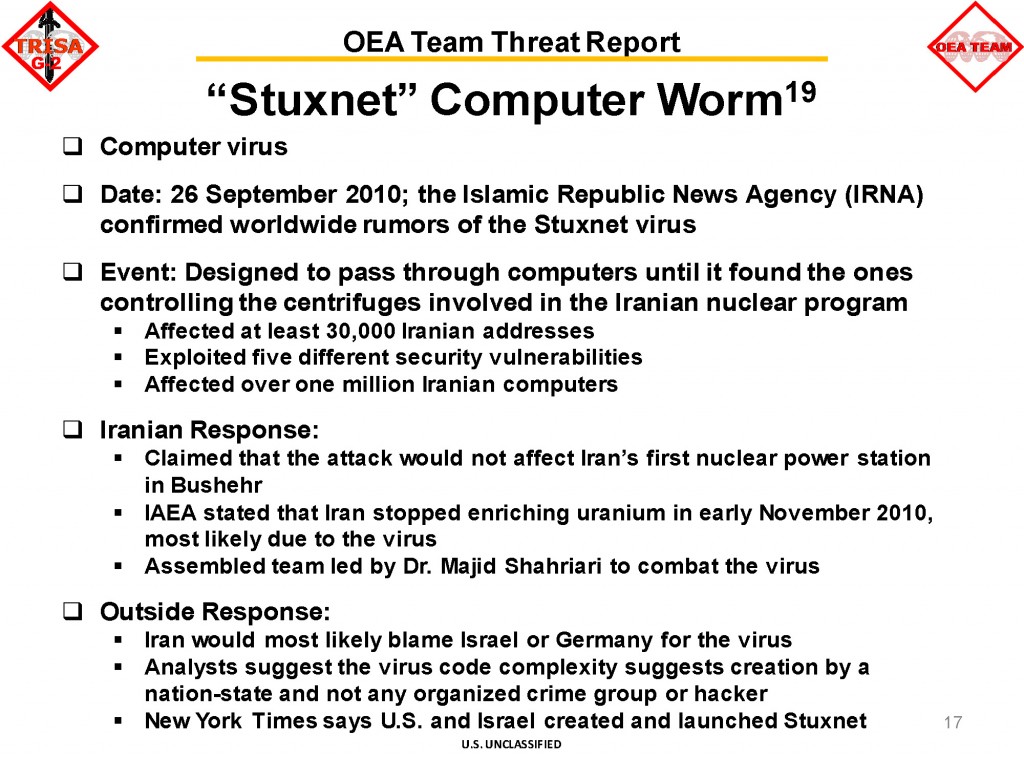

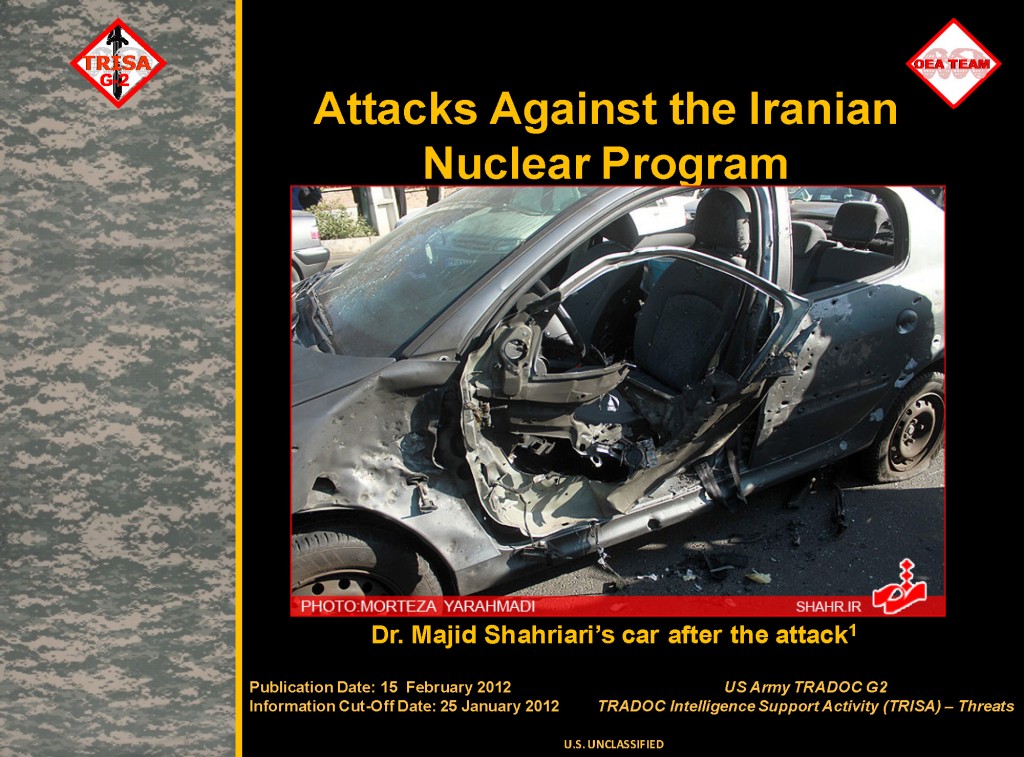

TRADOC G2 Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) OEA Team Threat Report

Iran News, Iran Hostage Crisis, Iran Contra Affair, Iran Flag, Iran Iraq War, Iran Castillo, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Map, Iran Sanctions, Iran President, Iran Air, Iran Allies, Iran Air Flight 655, Iran And Iraq, Iran Air Force, Iran Army, Iran And Russia, Iran Ayatollah, Iran And Israel, Iran And North Korea, Iran Barkley, Iran Before 1979, Iran Brown, Iran Birth Rate, Iran Bennett, Iran Boeing, Iran Beaches, Iran Beliefs, Iran Bonyads, Iran Brain Drain, Iran Contra Affair, Iran Castillo, Iran Capital, Iran Contra Affair Apush, Iran Currency, Iran Culture, Iran Contra Hearings, Iran Continent, Iran Cities, Iran Contra Affair Summary, Iran Deal, Iran Definition, Iran Deal Obama, Iran Demographics, Iran Dictator, Iran Death Penalty, Iran Democracy, Iran During The Cold War, Iran Desert, Iran Drone, Iran Election, Iran Economy, Iran Eory, Iran Embassy, Iran Etf, Iran Ethnic Groups, Iran Exports, Iran Embassy Usa, Iran Eisenhower, Iran Execution, Iran Flag, Iran Facts, Iran Food, Iran Flag Emoji, Iran Football, Iran Fighter Jet, Iranefarda, Iran Foreign Policy, Iran Foreign Minister, Iran Flag Meaning, Iran Government, Iran Gdp, Iran Gdp Per Capita, Iran Geography, Iran Government Type, Iran Green Revolution, Iran Guardian Council, Iran Gdp 2016, Iran Gay, Iran Gross Domestic Product, Iran Hostage Crisis, Iran Hostage Crisis Apush, Iran History, Iran Hostage Crisis President, Iran Hostage Crisis Definition, Iran Hostage Movie, Iran Hostage Crisis Timeline, Iran Human Rights, Iran Hostage Crisis Video, Iran Holidays, Iran Iraq War, Iran In The 70s, Iran Israel, Iran Isis, Iran In Syria, Iran Iraq Map, Iran Iraq War Causes, Iran India, Iran Iraq War Timeline, Iran Is Shia, Iran Jokes, Iran Jcpoa, Iran Judicial Branch, Iran Jewish Population, Iran Jet, Iran Jobs, Iran Jet Fighter, Iran Jersey, Iran Jewelry, Iran Japan, Iran Khodro, Iran King, Iran Kedisi, Iran Khamenei, Iran Kurds, Iran Khomeini, Iran Korea, Iran Kuwait, Iran Kidney Market, Imran Khan, Iran Launches Satellite, Iran Language, Iran Leader, Iran Live Tv, Iran Location, Iran Local Time, Iran Literacy Rate, Iran Life Expectancy, Iran Landscape, Iran Leadership, Iran Map, Iran Military, Iran Missile Test, Iran Missile, Iran Money, Iran Music, Iran Military Strength, Iran Military News, Iran Mountains, Iron Man, Iran News, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Weapons, Iran Nuclear, Iran News Today, Iran Navy, Iran National Football Team, Iran North Korea, Iran Natural Resources, Iran Newspaper, Iran On Map, Iran Oil, Iran Oil Production, Iran Official Language, Iran On World Map, Iran Opec, Iran Official Name, Iran Obama Deal, Iran Outline, Iran Oil Exports, Iran President, Iran Population, Iran People, Iranproud, Iran Pronunciation, Iran Presidential Election, Iran Prime Minister, Iran Persia, Iran Pictures, Iran Politics, Iran Qatar, Iran Qatar Relations, Iran Quizlet, Iran Quds Force, Iran Queen, Iran Quotes, Iran Qom, Iran Quora, Iran Qatar Pipeline, Iran Qaher 313, Iran Religion, Iran Revolution, Iran Russia, Iran Rial To Usd, Iran Rial, Iran Resources, Iran Race, Iran Restaurant, Iran Refugees, Iran Ruler, Iran Sanctions, Iran Satellite, Iran Supreme Leader, Iran Sunni Or Shia, Iran Syria, Iran So Far, Iran Shah, Iran Saudi Arabia, Iran Shia, Iran Soccer, Iran Time, Iran Tehran, Iran Today, Iran Tv, Iran Trump, Iran Tourism, Iran Timeline, Iran Type Of Government, Iran Travel, Iran Travel Ban, Iran Uk, Iran Us Relations, Iran Under The Shah, Iran Unemployment Rate, Iran Us News, Iran University Of Science And Technology, Iran Us Embassy, Iran Uzbekistan, Iran Us Nuclear Deal, Iran Us Dollar, Iran Vs Iraq, Iran Vs Usa, Iran Volleyball, Iran Visa, Iran Vs Israel, Iran Vs Saudi Arabia, Iran Vice President, Iran Vs Isis, Iran Volleyball Team, Iran Vote, Iran War, Iran Women, Iran Wiki, Iran Weather, Iran World Map, Iran Ww2, Iran World Cup, Iran Wrestling, Iran Wikitravel, Iran White Revolution, Iran Contra Affair, Iran Castillo, Iran Capital, Iran Contra Affair Apush, Iran X, Iran Currency, Iran Culture, Iran Contra Hearings, Iran Continent, Iran Cities, Iran Yemen, Iran Youtube, Iran Youth, Iran Year, Iran Yellow Pages, Iran Yazd, Iran Year Converter, Iran Young Population, Iran Youth Population, Iran Yahoo News, Iran Zip Code, Iran Zoroastrian, Iran Zamin, Iran Zabol, Iran Zarif, Iran Zagros Mountains, Iran Zamin Bank, Iran Zoo, Iran Zumba, Iran Zamin Tv, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Weapons, Iran Nuclear Program, Iran Nuclear Treaty, Iran Nuclear Deal Trump, Iran Nuclear Deal Obama, Iran Nuclear Deal 2015, Iran Nuclear Virus, Iran Nuclear Deal Explained, Iran Nuclear Deal Date, Iran Nuclear Agreement, Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act, Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act Of 2015, Iran Nuclear Arms Deal, Iran Nuclear Agreement 2015, Iran Nuclear Arsenal, Iran Nuclear Agreement Definition, Iran Nuclear Ambitions, Iran Nuclear Agreement Summary, Iran Nuclear Agreement Meets With Public Skepticism, Iran Nuclear Bomb, Iran Nuclear Bug, Iran Nuclear Ban, Iran Nuclear Bomb Threat, Iran Nuclear Bomb Test, Iran Nuclear Breakout Time, Iran Nuclear Bbc, Iran Nuclear Bomb Capability, Iran Nuclear Bill, Iran Nuclear Bad Deal, Iran Nuclear Crisis, Iran Nuclear Capability, Iran Nuclear Centrifuges, Iran Nuclear Compliance, Iran Nuclear Crisis Timeline, Iran Nuclear Crisis Summary, Iran Nuclear Capacity, Iran Nuclear Country, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Deal Trump, Iran Nuclear Deal Obama, Iran Nuclear Deal 2015, Iran Nuclear Deal Explained, Iran Nuclear Deal Definition, Iran Nuclear Deal Date, Iran Nuclear Deal Timeline, Iran Nuclear Deal Facts, Iran Nuclear Deal Political Cartoon, Iran Nuclear Energy, Iran Nuclear Enrichment, Iran Nuclear Explosion, Iran Nuclear Embargo, Iran Nuclear Emp, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Extension, Iran Nuclear Explained, Iran Nuclear Experts, Iran Nuclear Energy Conflict, Iran Nuclear Facilities, Iran Nuclear Facts, Iran Nuclear Facility Virus, Iran Nuclear Facilities Map, Iran Nuclear Facilities Underground, Iran Nuclear Framework, Iran Nuclear Framework Agreement, Iran Nuclear Fact Sheet, Iran Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Fuel, Iran Nuclear Geneva, Iran Nuclear Guardian, Iran Nuclear Graph, Iran Nuclear Game Theory, Iran Nuclear Gcc, Iran Nuclear Goals, Iran Nuclear Google Maps, Iran Getting Nuclear Weapons, Iran Going Nuclear, Iran Gets Nuclear Deal, Iran Nuclear Hack, Iran Nuclear History, Iran Nuclear Hack Documentary, Iran Nuclear History Timeline, Iran Nuclear Hack Ac Dc, Iran’s Nuclear History From The 1950s To 2005, Iran Nuclear Hearing, Iran Nuclear Holocaust, Iran Nuclear Hedging, Iran Nuclear Hoax, Iran Nuclear Inspections, Iran Nuclear Issue, Iran Nuclear Inspections 2017, Iran Nuclear Inspectors, Iran Nuclear Intentions And Capabilities, Iran Nuclear Israel, Iran Nuclear Icbm, Iran Nuclear Issue Summary, Iran Nuclear Jcpoa, Iran Nuclear Jokes, Iran Nuclear Joint Plan Of Action, Iran Nuclear June, Iran Nuclear June 30, Iran Nuclear Joint Comprehensive Plan Of Action, Iran Nuclear Joint Statement, Iran Nuclear Japan, Iran Nuclear January, Nuclear Iran Jeremy Bernstein, Iran Nuclear Kerry, Iran Nuclear Khamenei, Iran Nuclear Kazakhstan, Iran Nuclear Korea, Iran Nuclear Key Points, Iran’s Key Nuclear Sites, Iran Korea Nuclear Weapons, Iran Nuclear Deal Key Points, Iran Nuclear Scientist Killed, Iran Nuclear Deal Kerry, Iran Nuclear Launch, Iran Nuclear Latest News, Iran Nuclear Lausanne, Iran Nuclear Letter, Iran Nuclear Locations, Iran Nuclear Live, Iran Nuclear Lies, Iran Nuclear Law, Iran Nuclear Legislation, Iran Nuclear Laptop, Iran Nuclear Missiles, Iran Nuclear Missile Test, Iran Nuclear Meltdown, Iran Nuclear Movie, Iran Nuclear Monitoring, Iran Nuclear Missile Program, Iran Nuclear Meeting, Iran Nuclear Material, Iran Nuclear Map, Iran Nuclear Mountain, Iran Nuclear News, Iran Nuclear Negotiations, Iran Nuclear Non Proliferation Treaty, Iran Nuclear North Korea, Iran Nuclear Negotiations Timeline, Iran Nuclear Negotiations History, Iran Nuclear News Today, Iran Nuclear New York Times, Iran Nuclear Negotiation Team, Iran Nuclear Obama, Iran Nuclear Oil, Iran Nuclear Oil Prices, Iran Nuclear Oman, Iran Nuclear Option, Iran On Nuclear Deal, Iran On Nuclear Weapons, Iran On Nuclear Edge, Iran Obtaining Nuclear Weapons, Iran On Nuclear Program, Iran Nuclear Program, Iran Nuclear Power, Iran Nuclear Proliferation, Iran Nuclear Program Timeline, Iran Nuclear Power Plant, Iran Nuclear Program Virus, Iran Nuclear Plant, Iran Nuclear Policy, Iran Nuclear Program Obama, Iran Nuclear Program Worm, Iran Nuclear Quotes, Iran Nuclear Quora, Iran Nuclear Questions, Iran Nuclear Quest, Iran Qom Nuclear Site, Iran Nuclear Deal Quora, Iran Nuclear Deal Quotes, Iran Nuclear Deal Questions, Iran Nuclear Deal Quick Facts, Iran Nuclear Deal Q&a, Iran Nuclear Reactor, Iran Nuclear Reactor Hacked, Iran Nuclear Review Act, Iran Nuclear Review Act Of 2015, Iran Nuclear Russia, Iran Nuclear Range, Iran Nuclear Research, Iran Nuclear Regulatory Authority, Iran Nuclear Rubik’s Cube, Iran Nuclear Sanctions, Iran Nuclear Sites, Iran Nuclear Submarine, Iran Nuclear Scientist, Iran Nuclear Sanctions Timeline, Iran Nuclear Situation, Iran Nuclear Sites Map, Iran Nuclear Stockpile, Iran Nuclear State, Iran Nuclear Status, Iran Nuclear Treaty, Iran Nuclear Treaty Apush, Iran Nuclear Threat, Iran Nuclear Test, Iran Nuclear Talks, Iran Nuclear Timeline, Iran Nuclear Treaty Debate, Iran Nuclear Treaty 2015, Iran Nuclear Trump, Iran Nuclear Technology, Iran Nuclear Update, Iran Nuclear Us, Iran Nuclear Un, Iran Nuclear Underground Bunkers, Iran Nuclear Underground, Iran Nuclear Us Congress, Iran Nuclear Uranium, Iran Nuclear Usb, Iran Nuclear Uranium Enrichment, Iran Nuclear United States, Iran Nuclear Virus, Iran Nuclear Vote, Iran Nuclear Vienna, Iran Nuclear Vote Count, Iran Nuclear Video, Iran Nuclear Violations, Iran Nuclear Vote Date, Iran Nuclear Verification, Iran Nuclear Virus Ac\/dc, Iran Nuclear Veto, Iran Nuclear Weapons, Iran Nuclear Weapons Program, Iran Nuclear War, Iran Nuclear Weapons Threat, Iran Nuclear Weapons Deal, Iran Nuclear Worm, Iran Nuclear Weapons 2017, Iran Nuclear Weapons Test, Iran Nuclear Weapons Timeline, Iran Nuclear Weapons Treaty, Iran Nuclear Youtube, Iran Nuclear Yahoo Answers, Youtube With Nuclear Iran, Iran Nuclear Yahoo, Iran Nuclear Yemen, Iran Nuclear Deal Youtube, Iran Nuclear Deal Yahoo Answers, Iran Nuclear New York Times, Iran Nuclear Deal Yahoo, Iran Nuclear Program Youtube, Iran Nuclear Zarif, Iran Nuclear Deal Zarif, Iran Nuclear Deal Zucker, Iran Nuclear Free Zone, Iran Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, Nuclear War Now, Nuclear War Movies, Nuclear War Simulation, Nuclear War Definition, Nuclear War Game, Nuclear War Simulation Game, Nuclear War News, Nuclear War North Korea, Nuclear War Clock, Nuclear War Map, Nuclear War Aftermath, Nuclear War Alert, Nuclear War Art, Nuclear War Alarm, Nuclear War Articles, Nuclear War Anxiety, Nuclear War Animation, Nuclear War Agreement, Nuclear War Against North Korea, Nuclear War App, Nuclear War Board Game, Nuclear War Books, Nuclear War Bunker, Nuclear War Between Us And Russia, Nuclear War Bible, Nuclear War Blast Radius, Nuclear War Background, Nuclear War Bomb, Nuclear War Bbc, Nuclear War Between North Korea And America, Nuclear War Clock, Nuclear War Card Game, Nuclear War Coming, Nuclear War Close Calls, Nuclear War Cold War, Nuclear War Chances, Nuclear War Cartoon, Nuclear War Consequences, Nuclear War Cnn, Nuclear War China, Nuclear War Definition, Nuclear War Documentary, Nuclear War Donald Trump, Nuclear War Dream, Nuclear War Damage, Nuclear War Date, Nuclear War Drills, Nuclear War During The Cold War, Nuclear War Drills In Schools, Nuclear War Declared, Nuclear War Effects, Nuclear War Emergency Kit, Nuclear War End Of The World, Nuclear War End Times, Nuclear War Extinction, Nuclear War Essay, Nuclear War Expert, Nuclear War Effects On Environment, Nuclear War Eas, Nuclear War Example, Nuclear War Fallout Map, Nuclear War Facts, Nuclear War Films, Nuclear War Fallout, Nuclear War Fiction, Nuclear War Fear, Nuclear War From Space, Nuclear War Flash Game, Nuclear Warfare, Nuclear War Fallout Shelter, Nuclear War Game, Nuclear War Game Online, Nuclear War Gas Mask, Nuclear War Gif, Nuclear War Gear, Nuclear War Games Unblocked, Nuclear War Game Theory, Nuclear War Global Warming, Nuclear War Games Pc, Nuclear War Game Movie, Nuclear Warhead, Nuclear War History, Nuclear War Hoax, Nuclear War Hawaii, Nuclear War Happening, Nuclear War Happening Soon, Nuclear War Human Extinction, Nuclear Warheads By Country, Nuclear War Has Become Thinkable Again, Nuclear Warhead Count, Nuclear War Imminent, Nuclear War In The Bible, Nuclear War Inevitable, Nuclear War Is Coming, Nuclear War In North Korea, Nuclear War In 2017, Nuclear War In Chicago, Nuclear War In Korea, Nuclear War Images, Nuclear War In America, Nuclear War Japan, Nuclear War Jokes, Nuclear War John F Kennedy, Nuclear War Jerwood, Nuclear War Justification, Nuclear War Jimmy Cliff, Nuclear War Jazz, Nuclear War June 2015, Nuclear War Justified, Nuclear War Jericho, Nuclear War Korea, Nuclear War Kit, Nuclear War Kennedy, Nuclear War Korean Peninsula, Nuclear War Korea Us, Nuclear War Kim Jong Un, Nuclear War Killed All Life On Mars, Nuclear War Kickstarter, Nuclear War Killed The Dinosaurs, Nuclear War Korea 2017, Nuclear War Likely, Nuclear War Likelihood 2017, Nuclear War Lyrics, Nuclear War Los Angeles, Nuclear War Lyrics Sun Ra, Nuclear War Laws, Nuclear War Level, Nuclear War Lesson Plan, Nuclear War Looming, Nuclear War Leads To Extinction, Nuclear War Movies, Nuclear War Map, Nuclear War Meme, Nuclear War Meaning, Nuclear War May 13, Nuclear War Map Usa, Nuclear War Movie 1980s, Nuclear War Mask, Nuclear War May 13 2017, Nuclear War Mars, Nuclear War Now, Nuclear War North Korea, Nuclear War News, Nuclear War Now Forum, Nuclear War Now Bandcamp, Nuclear War North Korea Scenario, Nuclear War Now Store, Nuclear War Novels, Nuclear War News 2017, Nuclear War Not Going To Happen, Nuclear War On Mars, Nuclear War Outcome, Nuclear War Odds, Nuclear War On Us, Nuclear War Online Game, Nuclear War On The Horizon, Nuclear War On May 13, Nuclear War On United States, Nuclear War On Us Soil, Nuclear War Over Syria, Nuclear War Predictions, Nuclear War Possibility, Nuclear War Prank, Nuclear War Prophecy, Nuclear War Protection, Nuclear War Political Cartoons, Nuclear War Prep, Nuclear War Pictures, Nuclear War Plans, Nuclear War Podcast, Nuclear War Quotes, Nuclear War Quizlet, Nuclear War Quora, Nuclear War Questions, Nuclear War Quiz, Nuclear War Question Time, Nuclear War Quran, Nuclear War Queen Speech, Einstein Nuclear War Quote, Mao Nuclear War Quote, Nuclear War Russia, Nuclear War Reddit, Nuclear War Risk, Nuclear War Results, Nuclear War Russia Us, Nuclear War Race, Nuclear War Radiation, Nuclear War Reality, Nuclear War Radius, Nuclear War Rules, Nuclear War Simulation, Nuclear War Simulation Game, Nuclear War Survival Skills, Nuclear War Survival, Nuclear War Survival Kit, Nuclear War Sun Ra, Nuclear War Strategy Game, Nuclear War Survival Guide, Nuclear War Scenarios, Nuclear War Siren, Nuclear War Threat, Nuclear War Trump, Nuclear War Targets, Nuclear War Today, Nuclear War Treaty, Nuclear War Timeline, Nuclear War Targets In Us, Nuclear War There Goes My Career, Nuclear War Terms, Nuclear War Targets In Usa, Nuclear War Usa, Nuclear War Us, Nuclear War Update, Nuclear War Us Targets, Nuclear War Us Map, Nuclear War Usa Map, Nuclear War Us Russia, Nuclear War Upon Us, Nuclear War Under Trump, Nuclear War Uk, Nuclear War Video Game, Nuclear War Video, Nuclear War Vice, Nuclear War V14, Nuclear War Vs Thermonuclear War, Nuclear War Vice News, Nuclear War Victims, Nuclear War Vietnam, Nuclear War Video Clips, Nuclear War Vs Biological War, Nuclear War With Russia, Nuclear War With Korea, Nuclear War Warning, Nuclear War With China, Nuclear War With North Korea, Nuclear War Warning System, Nuclear War Will Not Happen, Nuclear War Wiki, Nuclear War What To Do, Nuclear War Will End The World, Nuclear War Games Xbox 360, Xkcd Nuclear War, Nuclear War Youtube, Nuclear War Yo La Tengo, Nuclear War Yahoo Answers, Nuclear War Year, Nuclear War Yemen, Nuclear War Yes No, Nuclear War Yo La Tengo Lyrics, Nuclear War Yo La, Nuclear War Movies Youtube, Ancient Nuclear War Youtube, Nuclear War Zone, Nuclear War Zombies, Nuclear War Zero Sum Game, Nuclear War Safe Zones, Nuclear War New Zealand, Nuclear War Twilight Zone, Nuclear War Strike Zones, Nuclear War Blast Zones, Nuclear War Free Zone, Nuclear War Safe Zones In Us, Nuclear Bomb, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Fusion, Nuclear War, Nuclear Family, Nuclear Fission, Nuclear Stress Test, Nuclear Option, Nuclear Triad, Nuclear Medicine, Nuclear Arms Race, Nuclear Attack, Nuclear Accidents, Nuclear Assault, Nuclear Arsenal, Nuclear Age, Nuclear Arms Race Cold War, Nuclear Apocalypse, Nuclear Alarm, Nuclear Annihilation, Nuclear Bomb, Nuclear Blast, Nuclear Blast Radius, Nuclear Bomb Test, Nuclear Bunker, Nuclear Bomb Shelter, Nuclear Binding Energy, Nuclear Blast Records, Nuclear Bone Scan, Nuclear Bomb Video, Nuclear Chemistry, Nuclear Clock, Nuclear Countries, Nuclear Chemistry Worksheet, Nuclear Charge, Nuclear Codes, Nuclear Cataract, Nuclear Chain Reaction, Nuclear Cardiology, Nuclear Cooling Tower, Nuclear Definition, Nuclear Decay, Nuclear Disasters, Nuclear Deterrence, Nuclear Decay Worksheet, Nuclear Disarmament, Nuclear Dna, Nuclear Detonation, Nuclear Decay Worksheet Answers, Nuclear Division, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Explosion, Nuclear Energy Definition, Nuclear Engineering, Nuclear Envelope, Nuclear Engineer Salary, Nuclear Energy Pros And Cons, Nuclear Energy Examples, Nuclear Explosion Gif, Nuclear Equations, Nuclear Fusion, Nuclear Family, Nuclear Fission, Nuclear Fusion Definition, Nuclear Football, Nuclear Fission Definition, Nuclear Fallout, Nuclear Family Definition, Nuclear Fusion Reactor, Nuclear Fallout Map, Nuclear Glass, Nuclear Gas Mask, Nuclear Gandhi, Nuclear Gun, Nuclear Gif, Nuclear Generator, Nuclear Gravity Bomb, Nuclear Games, Nuclear Gas, Nuclear Grenade, Nuclear Holocaust, Nuclear Heart Test, Nuclear Half Life, Nuclear Hazard Symbol, Nuclear Holocaust Movies, Nuclear Hormone Receptors, Nuclear Hoax, Nuclear History, Nuclear Household, Nuclear Hand Grenade, Nuclear Imaging, Nuclear Incidents, Nuclear In Spanish, Nuclear Isotopes, Nuclear Icebreaker, Nuclear Icbm, Nuclear Issues, Nuclear Industry, Nuclear Icon, Nuclear Instruments And Methods, Nuclear Jobs, Nuclear Japan, Nuclear Jet Engine, Nuclear Jokes, Nuclear Jellyfish, Nuclear Jet, Nuclear Js, Nuclear Jobs Overseas, Nuclear Jobs Florida, Nuclear Jellyfish Of New Jersey, Nuclear Korea, Nuclear Korean Noodles, Nuclear Kidney Test, Nuclear Kenyan Sand Boa, Nuclear Kinetic Energy, Nuclear Key, Nuclear Kit, Nuclear Keychain, Nuclear Kill Radius, Nuclear Kid, Nuclear Localization Signal, Nuclear Lamina, Nuclear Launch Codes, Nuclear Logo, Nuclear Lyrics, Nuclear Launch Detected, Nuclear Lake, Nuclear Launch, Nuclear Lamins, Nuclear Leak, Nuclear Medicine, Nuclear Medicine Technologist, Nuclear Membrane, Nuclear Missile, Nuclear Meltdown, Nuclear Membrane Function, Nuclear Map, Nuclear Membrane Definition, Nuclear Medicine Technologist Jobs, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, Nuclear News, Nuclear Nations, Nuclear North Korea, Nuclear Notation, Nuclear Noodles, Nuclear Norm, Nuclear Navy, Nuclear Nadal, Nuclear Nucular, Nuclear Option, Nuclear Oncology, Nuclear Option 2013, Nuclear Option Harry Reid, Nuclear Overhauser Effect, Nuclear Outage, Nuclear Operator Salary, Nuclear Or Nucular, Nuclear Operator, Nuclear Option Fallout 4, Nuclear Power, Nuclear Power Plants, Nuclear Proliferation, Nuclear Power Plants In Us, Nuclear Physics, Nuclear Physicist, Nuclear Power Definition, Nuclear Power Pros And Cons, Nuclear Pharmacy, Nuclear Power Plants In Texas, Nuclear Quotes, Nuclear Quadrupole Resonance, Nuclear Questions, Nuclear Quiz, Nuclear Quality Assurance, Nuclear Quizlet, Nuclear Quadrupole Moment, Nuclear Quantum Effects, Nuclear Quality Assurance Jobs, Nuclear Quantum Numbers, Nuclear Reactor, Nuclear Radiation, Nuclear Reaction, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Nuclear Reactor Definition, Nuclear Reactor Diagram, Nuclear Receptor, Nuclear Reactors In Us, Nuclear Rocket, Nuclear Reaction Worksheet, Nuclear Stress Test, Nuclear Symbol, Nuclear Submarine, Nuclear Sclerosis, Nuclear Sign, Nuclear Shadow, Nuclear Shelter, Nuclear Secrecy, Nuclear Siren, Nuclear Scan, Nuclear Triad, Nuclear Throne, Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, Nuclear Test, Nuclear Technician, Nuclear Threat, Nuclear Throne Together, Nuclear Throne Wiki, Nuclear Technology, Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Apush, Nuclear Umbrella, Nuclear Uranium, Nuclear Uses, Nuclear Utilization Theory, Nuclear Ultrasound, Nuclear Us, Nuclear Usa, Nuclear Unit, Nuclear Union, Nuclear Ukraine, Nuclear Vs Atomic, Nuclear Vote, Nuclear Vs Nucular, Nuclear Valdez, Nuclear Vs Solar, Nuclear Vs Coal, Nuclear Vs Hydrogen Bomb, Nuclear Vs Extended Family, Nuclear Vs Mitochondrial Dna, Nuclear Video, Nuclear War, Nuclear Weapons, Nuclear Winter, Nuclear Waste, Nuclear Waste Disposal, Nuclear War Now, Nuclear Weapons Definition, Nuclear War Movies, Nuclear Waste Policy Act, Nuclear Weapons Facts, Nuclear X Ray, Nuclear X, Nuclear Explosion, Nuclear X Met Rx, Nuclear Explosion Gif, Nuclear X Ray Technician Salary, Nuclear Explosion In Space, Nuclear Explosion Video, Nuclear Explosion Simulator, Nuclear Explosion Radius, Nuclear Yield, Nuclear Yield Map, Nuclear Youtube, Nuclear Yellow, Nuclear Yellow Cake, Nuclear Yacht, Nuclear Yemen, Nuclear Ymir, Nuclear Yap, Nuclear Yucca Mountain, Nuclear Zone, Nuclear Zomboy, Nuclear Zero, Nuclear Zombies, Nuclear Zomboy Lyrics, Nuclear Zone Theory, Nuclear Zone Hypothesis, Nuclear Zec, Nuclear Zone Terraforming Mars, Nuclear Zone In Russia, Us Army Intelligence Support Activity, Us Army Intelligence Officer, Us Army Intelligence Mos, Us Army Intelligence Center Of Excellence, Us Army Intelligence And Security Command, Us Army Intelligence School, Us Army Intelligence Jobs, Us Army Intelligence Corps, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Salary, Us Army Intelligence Command, Us Army Intelligence And Security Command, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Salary, Us Army Intelligence Agency, Us Army Intelligence Analyst, Us Army Intelligence And Interrogation Handbook, Us Army Intelligence And Security Command Charlottesville Va, Us Army Intelligence Ace, Us Army Intelligence And Threat Analysis Center, Us Army Intelligence And Information Warfare Directorate, Us Army Intelligence Agent, Us Army Intelligence Bases, Us Army Intelligence Badge, Us Army Intelligence Branch Insignia, Us Army Intelligence Branch Manager, Us Army Intelligence Badge Credentials, Us Army Intelligence Bolc, Us Army Business Intelligence, Us Military Intelligence Budget, Us Military Intelligence Branch, Us Military Intelligence Badge, Us Army Intelligence Center Of Excellence, Us Army Intelligence Center, Us Army Intelligence Corps, Us Army Intelligence Command, Us Army Intelligence Cycle, Us Army Intelligence Careers, Us Army Intelligence Center Of Excellence Address, Us Army Intelligence Coe Ft Huachuca Az, Us Army Intelligence Creed, Us Army Intelligence Charlottesville Va, Us Army Intelligence Doctrine, Us Army Intelligence Disciplines, Us Army Intelligence Duty Stations, Us Army Intelligence Department, Us Army Intelligence Division, Us Military Intelligence Division, Us Military Intelligence Doctrine, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Job Description, Us Army Element Defense Intelligence Agency, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Devens, Us Army Intelligence Enlisted, Us Military Intelligence Estimates 1946, Us Army Emotional Intelligence, Us Army Military Intelligence Enlisted, Us Army Intelligence Center Of Excellence, Us Military Intelligence Report Ew-pa 128, Us Army Intelligence Center Of Excellence Fort Huachuca, Us Army To Provide Equipment Intelligence To Fight Boko Haram, Us Army Element Defense Intelligence Agency, Us Army Elm Southcom Joint Intelligence Center, Us Army Intelligence Field Manual, Us Army Intelligence Foundry, Us Army Intelligence Fort Huachuca, Us Army Field Intelligence, Us Army Foreign Intelligence Activity, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Holabird, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Devens, Us Army Intelligence Coe Ft Huachuca Az, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Huachuca, Us Army Intelligence School Fort Holabird Md, Us Army Intelligence Germany, Us Army Intelligence G2, Us Army Geospatial Intelligence, Us Army Military Intelligence General Officers, Us Army National Ground Intelligence Center, Us Army 902d Military Intelligence Group, Us Army National Guard Intelligence, Commanding General Us Army Intelligence And Security Command, Us Army National Guard Military Intelligence Units, Us Army Intelligence History, Us Army Intelligence Headquarters, Us Army Human Intelligence, Us Military Intelligence Handbook, Us Army Human Intelligence Officer, Us Army Military Intelligence Hall Of Fame, Us Army Intelligence Fort Huachuca, Us Army Intelligence Agency History, Us Army Intelligence And Interrogation Handbook, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Holabird, Us Army Intelligence Insignia, Us Army Imagery Intelligence, Us Army Imagery Intelligence (Imint) Courses, Us Army Report Intelligence Information Training, Us Army Intelligence And Interrogation Handbook, Us Army Intelligence Branch Insignia, Us Army Intelligence And Information Warfare Directorate, Us Army Intelligence And Security Command (Inscom), Us Army Intelligence Jobs, Us Military Intelligence Jobs, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Job Description, Us Army Civilian Intelligence Jobs, Us Army Elm Southcom Joint Intelligence Center, Us Army Military Intelligence South Korea, Us Army Intelligence Logo, Us Army Military Intelligence Logo, Us Army Intelligence Mos List, Us Army Military Intelligence Mos List, Us Army Military Intelligence Reading List, Us Army Intelligence Mos, Us Army Intelligence Museum, Us Army Intelligence Manual, Us Army Intelligence Motto, Us Army Intelligence Mos List, Us Army Military Intelligence Officer, Us Army Military Intelligence Mos, Us Army Military Intelligence School, Us Army Military Intelligence Officer Career Progression, Us Army Military Intelligence Officer Basic Course, Us Military Intelligence Name, Us Army National Ground Intelligence Center, Us Army National Guard Intelligence, Us Army National Guard Military Intelligence Units, Us Army Intelligence Officer, Us Army Intelligence Officer Salary, Us Army Intelligence Oversight, Us Army Intelligence Officer Career Path, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Training, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Online Training, Us Army Intelligence Organizations, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Powerpoint, Us Army Intelligence Officer Basic Course, Us Military Intelligence Operations, Us Army Intelligence Patches, Us Army Intelligence Preparation Of The Battlefield, Us Army Intelligence Process, Us Army Intelligence Publications, Us Army Intelligence Project Stargate, Us Army Intelligence Pdf, Us Army Military Intelligence Patches, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Powerpoint, Us Army Military Intelligence Pins, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Pay, Us Army Military Intelligence Quotes, Us Army Intelligence Requirements, Us Army Intelligence Recruiting, Us Army Intelligence Ranks, Us Army Intelligence Regulations, Us Army Intelligence Ring, Us Military Intelligence Report Ew-pa 128, Us Army Report Intelligence Information Training, Us Army Reserve Intelligence Units, Us Military Intelligence Ranks, Us Army Ranger Intelligence Officer, Us Army Intelligence Support Activity, Us Army Intelligence School, Us Army Intelligence Specialist, Us Army Intelligence Support Activity Recruitment, Us Army Intelligence Security Command, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Holabird, Us Army Intelligence Surveillance And Reconnaissance, Us Army Intelligence Service, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Devens, Us Army Intelligence School Ft Huachuca, Us Army Intelligence Threat Analysis Center, Us Army Intelligence Test, Us Army Intelligence Training, Us Army Intelligence Training Center, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Training, Us Army Intelligence Officer Training, Us Army Alpha Intelligence Test, Us Army Intelligence Analyst Training, Us Army Intelligence Oversight Online Training, Us Army Intelligence Preparation Of The Battlefield, Us Army Intelligence Units, Us Army Intelligence Units Vietnam, Us Military Intelligence University, Us Army Reserve Intelligence Units, Us Army Military Intelligence Unit Patches, Us Army National Guard Military Intelligence Units, Us Army Intelligence Center And School Usaics, Us Army Intelligence Vietnam, Us Army Intelligence Charlottesville Va, Us Army Intelligence Warrant Officer, Us Army Intelligence Ww2, Us Army Intelligence Wiki, Us Army Intelligence Wwii, Us Army Intelligence World War 2, Us Military Intelligence Ww2, Us Army Weapons Intelligence Course, Us Army Military Intelligence Warrant Officer, Us Army Intelligence And Information Warfare Directorate, What Does Us Army Intelligence Do,Threat Definition, Threat Level Midnight, Threat Synonym, Threat In Spanish, Threat Modeling, Threat Stack, Threat Meaning, Threat Dynamics, Threat Intelligence, Threat Assessment, Threat Assessment, Threat Analysis, Threat Awareness And Reporting Program, Threat Antonym, Threat Actor, Threat Agent, Threat Assessment Model, Threat Assessment Training, Threat And Error Management, Threat Advice, Threat Based Threads, Threat Beast, Threat Brief, Threat Bias, Threat Basketball, Threat Board, Threat Blocked Avast, Threat Behavior, Threat Based Risk Assessment, Threat Blog, Threatconnect, Threatcrowd, Threat Charges, Threat Cloud, Threat Crime Cause Death\/gbi, Threat Ck2, Threat Control Override, Threatcon, Threatcon Delta, Threat Crime, Threat Definition, Threat Dynamics, Threat Detection, Threat Define, Threat Def, Threat Defense, Threat Display, Threat Detection And Response, Threat Disposal Nier, Threat Dynamics Hours, Threat En Espanol, Threat Expert, Threat Exchange, Threat Emulation, Threat Examples, Threat Error Management, Threat Environment, Threat Ender Crossword Clue, Threat Encyclopedia, Threat Emitter, Threat From North Korea, Threat Feeds, Threat From Xor, Threat Finance, Threat Fire, Threat From Russia, Threat From Above, Threat From The Thicket, Threat Finance Jobs, Threat From The Sea, Threat Grid, Threat Gif, Threat Group, Threat Generator, Threat Geek, Threat Graph, Threatguard, Threat Grid Login, Threat Group-4127, Threat Grid Api, Threat Hunting, Threathoops, Threat Hunting Tools, Threat Hunting With Splunk, Threat Hunting Training, Threat Hunting Techniques, Threat Hypothesis, Threat Has Been Detected, Threat Hunting Definition, Threat Hunting Summit, Threat In Spanish, Threat Intelligence, Threat Intelligence Feeds, Threat Intelligence Platform, Threat Intel, Threat In French, Threat Icon, Threat Intelligence Analyst, Threat Identification, Threat Intelligence Definition, Threat Jay Z Mp3, Threat Jay, Threat Journal, Threat Jokes, Threat Jail Time, Threat Jay Z Genius, Thread Java, Threat Jay Z Instrumental, Threat Jay Z Listen, Threat Jewellery, Threat Knowledge Group, Threat Kill Chain, Threat Level Midnight, Threat Knowledge, Threat Knowledge Group Isis, Threat Knights Of Pen And Paper, Threat Level Midnight Full Movie, Threat Level, Threat Level Midnight Episode, Threat Level Midnight Quotes, Threat Level Midnight, Threat Level Midnight Full Movie, Threat Level, Threat Level Midnight Episode, Threat Level Midnight Quotes, Threat Level Midnight Song, Threat Landscape, Threat Level Delta, Threat Level Midnight Poster, Threat Level Orange, Threat Modeling, Threat Meaning, Threat Matrix, Threat Map, Threat Management, Threat Management Group, Threat Modeling Tool, Threat Meme, Threat Modeling Designing For Security, Threat Management Gateway, Threat Note, Threat Neutralized, Threat North Korea, Threat Net, Threat Null, Threat News, Threat Narrative, Threat Neverwinter, Threat Networks, Threat Name Ws.reputation.1, Threat Of New Entrants, Threat Of Substitutes, Threat Of Joy Lyrics, Threat Of Nuclear War, Threat Of Joy, Threat Of War, Threat Of North Korea, Threat Of Substitute Products, Threat Of Terrorism, Threat Of Joy Chords, Threat Post, Threat Payday 2, Threat Pattern, Threat Prevention, Threat Perception, Threat Protection, Threat Profile, Threat Past Tense, Threat Point, Threat Plates, Threat Quotes, Threatquotient, Threat Questionnaire, Thread Queue, Threat Quotes And Sayings, Threat Quarantine, Threat Quotes In Hindi, Threat Quotes From Movies, Threat Response Solutions, Threat Response, Threat Report, Threat Rapper, Threat Range Pathfinder, Threat Rhyme, Threat Rigidity, Threat Research, Threat Radar, Threat Risk Assessment, Threat Synonym, Threat Stack, Threat Signal, Threat Simulation Theory, Threatstream, Threat Stack Careers, Threat Spanish, Threat Scan, Threat Scenarios, Threat Suppression, Threat To Survival, Threat To Internal Validity, Threat Thesaurus, Threat Tec, Threattrack, Threat To Biodiversity, Threat To Society, Threat To Validity, Threat To National Security, Threat To Us, Thread Up, Threat Update, Threat Us, Threat Used In A Sentence, Threat Uk, Threat Urban Dictionary, Thread Up Mens, Thread Up Review, Thread Up Maternity, Thread Up Sell, Threat Vector, Threat Vs Vulnerability, Threat Vulnerability Risk, Threat Vector Definition, Threat Vulnerability Assessment, Threat Verb, Threat Vs Warning, Threat Vault, Threat Vs Consequence, Threat Vs Challenge, Threat Wire, Threat With A Deadly Weapon, Threat Watch, Threat Wiki, Threat Warning, Thread Wallets, Threat Words, Threat Working Group, Threat Wow, Threat With A Gun, Threat X, Threat X Vulnerability = Risk, Threat And Risk, Threat X Impact, Threat Exchange, Threat Xword, X Factor Threat, Threat X3, X2 Threat, Xml Threat Protection In Datapower, Treat You Better Lyrics, Treat Yo Self, Treat You Better, Treat Yo Self Gif, Treat Your Feet, Treat You Better Chords, Treat Yo Self Meme, Treat Yo Self Episode, Treat Yo Self Day, Treat Yourself Meme, Threat Zero, Threat T\u0142umaczenie, Threat Zone, Thread Zigbee, Thread Zap, Zika Threat, Zp Theart, Zonealarm Threat Emulation, Zombie Threat, Zombie Threat Level,

You must be logged in to post a comment.