The Cuban Missile Crisis (known as the October Crisis in Cuba or Caribbean Crisis (Russ: Kарибский кризис) in the USSR) was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War. In August 1962, after some unsuccessful operations by the U.S. to overthrow the Cuban regime (Bay of Pigs, Operation Mongoose), the Cuban and Soviet governments secretly began to build bases in Cuba for a number ofmedium-range and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles (MRBMs and IRBMs) with the ability to strike most of the continental United States. This action followed the 1958 deployment of Thor IRBMs in the UK (Project Emily) and Jupiter IRBMs to Italy and Turkey in 1961 – more than 100 U.S.-built missiles having the capability to strike Moscow with nuclear warheads. On October 14, 1962, a United States Air Force U-2 plane on a photoreconnaissancemission captured photographic proof of Soviet missile bases under construction in Cuba.

The ensuing crisis ranks with the Berlin Blockade as one of the major confrontations of the Cold War and is generally regarded as the moment in which the Cold War came closest to turning into a nuclear conflict.[1] It also marks the first documented instance of the threat of mutual assured destruction (MAD) being discussed as a determining factor in a major international arms agreement.[2][3]

The United States considered attacking Cuba via air and sea, and settled on a military “quarantine” of Cuba. The U.S. announced that it would not permit offensive weapons to be delivered to Cuba and demanded that the Soviets dismantle the missile bases already under construction or completed in Cuba and remove all offensive weapons. The Kennedy administration held only a slim hope that the Kremlin would agree to their demands, and expected a military confrontation. On the Soviet side, Premier Nikita Khrushchev wrote in a letter to Kennedy that his quarantine of “navigation in international waters and air space” constituted “an act of aggression propelling humankind into the abyss of a world nuclear-missile war.”

The Soviets publicly balked at the U.S. demands, but in secret back-channel communications initiated a proposal to resolve the crisis. The confrontation ended on October 28, 1962, when President John F. Kennedy and United Nations Secretary-General U Thant reached a public and secret agreement with Khrushchev. Publicly, the Soviets would dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba and return them to the Soviet Union, subject to United Nations verification, in exchange for a U.S. public declaration and agreement never to invade Cuba. Secretly, the U.S. agreed that it would dismantle all U.S.-built Thor and Jupiter IRBMs deployed in Europe and Turkey.

Only two weeks after the agreement, the Soviets had removed the missile systems and their support equipment, loading them onto eight Soviet ships from November 5–9. A month later, on December 5 and 6, the Soviet Il-28 bombers were loaded onto three Soviet ships and shipped back to Russia. The quarantine was formally ended at 6:45 pm EDT on November 20, 1962. Eleven months after the agreement, all American weapons were deactivated (by September 1963). An additional outcome of the negotiations was the creation of the Hotline Agreement and the Moscow–Washington hotline, a direct communications link between Moscow and Washington, D.C.

Earlier actions by the United States

In 1959 US PGM-19 Jupiter intermediate range ballistic missiles targeting the USSR were deployed in Italy and Turkey.

In 1959 Cuban revolution took place and under the new government of Fidel Castro Cuba allied with the USSR. However, for a Latin American country to ally openly with the USSR was regarded by the US government as unacceptable. Such an involvement would also directly defy the Monroe Doctrine; a United States policy which, originally conceived to limit European power’s involvement in the Western Hemisphere, expanded to include all other major powers. The aim of the doctrine is to make sure the United States is the only hegemonic power in the Americas and keeping all others out of its “backyard”.

Bay of Pigs Invasion was launched in April 1961 under President John F. Kennedy by Central Intelligence Agency-trained forces of Cuban exiles but the invasion failed and the United States were embarrassed publicly. Afterward, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower told Kennedy that “the failure of the Bay of Pigs will embolden the Soviets to do something that they would otherwise not do.”[4]:10 The half-hearted invasion left Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and his advisers with the impression that Kennedy was indecisive and, as one Soviet adviser wrote, “too young, intellectual, not prepared well for decision making in crisis situations … too intelligent and too weak.”[4] U.S. covert operations continued in 1961 with the unsuccessful Operation Mongoose.[5]

In addition, Khrushchev’s impression of Kennedy’s weakness was confirmed by the President’s soft response during the Berlin Crisis of 1961, particularly the building of the Berlin Wall. Speaking to Soviet officials in the aftermath of the crisis, Khrushchev asserted, “I know for certain that Kennedy doesn’t have a strong background, nor, generally speaking, does he have the courage to stand up to a serious challenge.” He also told his son Sergei that on Cuba, Kennedy “would make a fuss, make more of a fuss, and then agree.”[6]

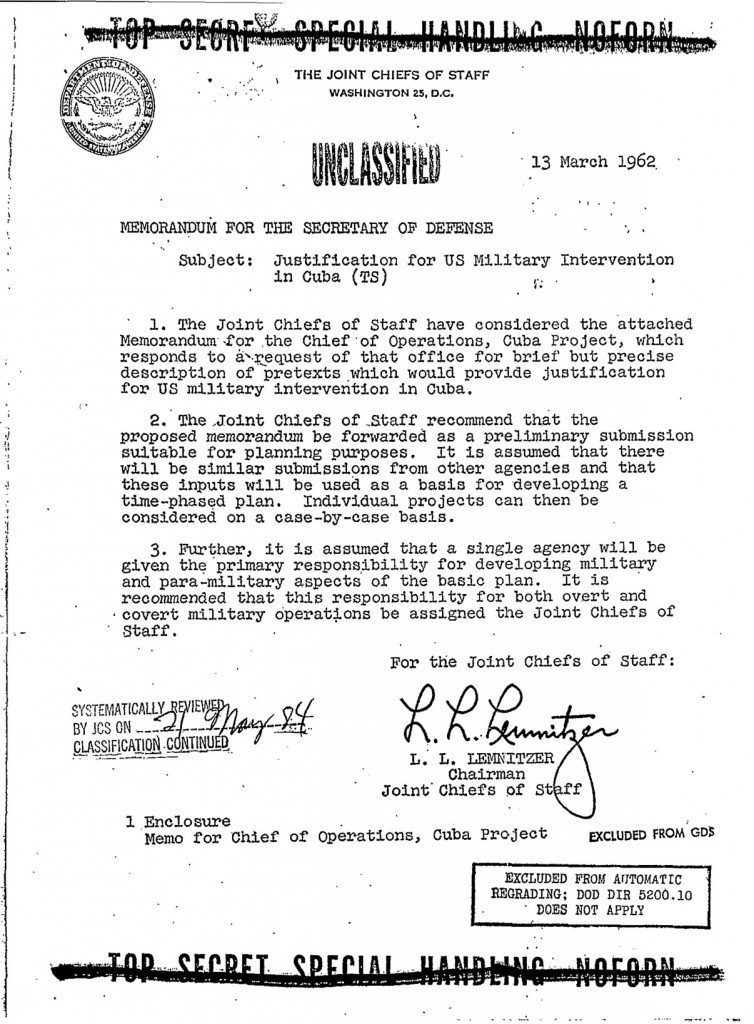

In January 1962, General Edward Lansdale described plans to overthrow the Cuban Government in a top-secret report (partially declassified 1989), addressed to President Kennedy and officials involved withOperation Mongoose.[5] CIA agents or “pathfinders” from the Special Activities Division were to be infiltrated into Cuba to carry out sabotage and organization, including radio broadcasts.[7] In February 1962, the United States launched an embargo against Cuba,[8] and Lansdale presented a 26-page, top-secret timetable for implementation of the overthrow of the Cuban Government, mandating that guerrilla operations begin in August and September, and in the first two weeks of October: “Open revolt and overthrow of the Communist regime.”[5]

[edit]Balance of power

When Kennedy ran for president in 1960, one of his key election issues was an alleged “missile gap“, with the Soviets leading.

In fact, the United States led the Soviets. In 1961, the Soviets had only four intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). By October 1962, they may have had a few dozen, although some intelligence estimates were as high as 75.[9]

The United States, on the other hand, had 170 ICBMs and was quickly building more. It also had eight George Washington and Ethan Allen class ballistic missile submarines with the capability to launch 16 Polarismissiles each with a range of 2,200 kilometres (1,400 mi).

Khrushchev increased the perception of a missile gap when he loudly boasted that the USSR was building missiles “like sausages” whose numbers and capabilities actually were nowhere close to his assertion. However, the Soviets did have medium-range ballistic missiles in quantity, about 700 of them.[9]

In his memoirs published in 1970, Khrushchev wrote, “In addition to protecting Cuba, our missiles would have equalized what the West likes to call ‘the balance of massive nuclear missiles around the globe.’” [9]

[edit]Soviet deployment of missiles in Cuba

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev conceived in May 1962 the idea of countering the United States’ growing lead in developing and deploying strategic missiles by placing Soviet intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. Khrushchev was also reacting in part to the Jupiter intermediate-range ballistic missiles which the United States had installed in Turkey during April 1962.[9]

From the very beginning, the Soviet’s operation entailed elaborate denial and deception, known in the USSR as Maskirovka.[10] All of the planning and preparation for transporting and deploying the missiles were carried out in the utmost secrecy, with only a very few told the exact nature of the mission. Even the troops detailed for the mission were given misdirection, told they were headed for a cold region and outfitted with ski boots, fleece-lined parkas, and other winter equipment.[10] The Soviet code name, Operation Anadyr, was also the name of a river flowing into the Bering Sea, the name of the capital of Chukotsky District, and a bomber base in the far eastern region. All these were meant to conceal the program from both internal and external audiences.[10]

In early 1962, a group of Soviet military and missile construction specialists accompanied an agricultural delegation to Havana. They obtained a meeting with Cuban leader Fidel Castro. The Cuban leadership had a strong expectation that the U.S. would invade Cuba again and they enthusiastically approved the idea of installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. Specialists in missile construction under the guise of “machine operators,” “irrigation specialists,” and “agricultural specialists” arrived in July.[10] Marshal Sergei Biryuzov, chief of the Soviet Rocket Forces, led a survey team that visited Cuba. He told Khrushchev that the missiles would be concealed and camouflaged by the palm trees.[9]

The Cuban leadership was further upset when in September Congress approved U.S. Joint Resolution 230, which authorized the use of military force in Cuba if American interests were threatened.[11] On the same day, the U.S. announced a major military exercise in the Caribbean, PHIBRIGLEX-62, which Cuba denounced as a deliberate provocation and proof that the U.S. planned to invade Cuba.[11][12]

Khrushchev and Castro agreed to place strategic nuclear missiles secretly in Cuba. Like Castro, Khrushchev felt that a U.S. invasion of Cuba was imminent, and that to lose Cuba would do great harm to the communist cause, especially in Latin America. He said he wanted to confront the Americans “with more than words… the logical answer was missiles.”[13]:29 The Soviets maintained their tight secrecy, writing their plans longhand, which were approved by Rodion Malinovsky on July 4 and Khrushchev on July 7.

The Soviet leadership believed, based on their perception of Kennedy’s lack of confidence during the Bay of Pigs Invasion, that he would avoid confrontation and accept the missiles as a fait accompli.[4]:1 On September 11, the Soviet Union publicly warned that a U.S. attack on Cuba or on Soviet ships carrying supplies to the island would mean war.[5] The Soviets continued their Maskirovka program to conceal their actions in Cuba. They repeatedly denied that the weapons being brought into Cuba were offensive in nature. On September 7, Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin assured U.S. Ambassador to the United NationsAdlai Stevenson that the USSR was supplying only defensive weapons to Cuba. On September 11, the Soviet News Agency TASS announced that the Soviet Union has no need or intention to introduce offensive nuclear missiles into Cuba. On October 13, Dobrynin was questioned by former Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles about whether the Soviets plan to put offensive weapons in Cuba. He denied any such plans.[11] And again on October 17, Soviet embassy official Georgy Bolshakov brought President Kennedy a “personal message” from Khrushchev reassuring him that “under no circumstances would surface-to-surface missiles be sent to Cuba.[11]:494

As early as August 1962, the United States suspected the Soviets of building missile facilities in Cuba. During that month, its intelligence services gathered information about sightings by ground observers of Russian-built MiG-21 fighters and Il-28 light bombers. U-2 spyplanes found S-75 Dvina (NATO designation SA-2) surface-to-air missile sites at eight different locations. CIA director John A. McCone was suspicious. On August 10, he wrote a memo to President Kennedy in which he guessed that the Soviets were preparing to introduce ballistic missiles into Cuba.[9] On August 31, Senator Kenneth Keating (R-New York), who probably received his information from Cuban exiles in Florida,[9] warned on the Senate floor that the Soviet Union may be constructing a missile base in Cuba.[5]

Air Force General Curtis LeMay presented a pre-invasion bombing plan to Kennedy in September, while spy flights and minor military harassment from U.S. forces at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base were the subject of continual Cuban diplomatic complaints to the U.S. government.[5]

The first consignment of R-12 missiles arrived on the night of September 8, followed by a second on September 16. The R-12 was the first operational intermediate-range ballistic missile, the first missile ever mass-produced, and the first Soviet missile deployed with a thermonuclear warhead. It was a single-stage, road-transportable, surface-launched, storable propellant fueled missile that could deliver a megaton-classnuclear weapon.[14] The Soviets were building nine sites—six for R-12 medium-range missiles (NATO designation SS-4 Sandal) with an effective range of 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) and three for R-14 intermediate-range ballistic missiles (NATO designation SS-5 Skean) with a maximum range of 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi).[15]

[edit]Cuba positioning

On October 7, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós spoke at the UN General Assembly: “If … we are attacked, we will defend ourselves. I repeat, we have sufficient means with which to defend ourselves; we have indeed our inevitable weapons, the weapons, which we would have preferred not to acquire, and which we do not wish to employ.”

[edit]Missiles reported

The missiles in Cuba allowed the Soviets to effectively target almost the entire continental United States. The planned arsenal was forty launchers. The Cuban populace readily noticed the arrival and deployment of the missiles and hundreds of reports reached Miami. U.S. intelligence received countless reports, many of dubious quality or even laughable, and most of which could be dismissed as describing defensive missiles. Only five reports bothered the analysts. They described large trucks passing through towns at night carrying very long canvas-covered cylindrical objects that could not make turns through towns without backing up and maneuvering. Defensive missiles could make these turns. These reports could not be satisfactorily dismissed.[16]

U-2 reconnaissance photograph of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Missile transports and tents for fueling and maintenance are visible. Courtesy of CIA

[edit]U-2 flights find missiles

Despite the increasing evidence of a military build-up on Cuba, no U-2 flights were made over Cuba from September 5 to October 14. The first problem that caused the pause in reconnaissance flights took place on August 30, an Air Force Strategic Air Command U-2 flew over Sakhalin Island in the Far East by mistake. The Soviets lodged a protest and the U.S. apologized. Nine days later, a Taiwanese-operated U-2 [17][18] was lost over western China, probably to a SAM. U.S. officials worried that one of the Cuban or Soviet SAMs in Cuba might shoot down a CIA U-2, initiating another international incident. At the end of September, Navy reconnaissance aircraft photographed the Soviet ship Kasimov with large crates on its deck the size and shape of Il-28 light bombers.[9]

On October 12, the administration decided to transfer the Cuban U-2 reconnaissance missions to the Air Force. In the event another U-2 was shot down, they thought a cover story involving Air Force flights would be easier to explain than CIA flights. There was also some evidence that the Department of Defense and the Air Force lobbied to get responsibility for the Cuban flights.[9] When the reconnaissance missions were re-authorized on October 8, weather kept the planes from flying. The U.S. first obtained photographic evidence of the missiles on October 14 when a U-2 flight piloted by Major Richard Heyser took 928 pictures, capturing images of what turned out to be an SS-4 construction site at San Cristóbal, Pinar del Río Province, in western Cuba.[19]

[edit]President notified

On October 15, the CIA’s National Photographic Intelligence Center reviewed the U-2 photographs and identified objects that they interpreted as medium range ballistic missiles. That evening, the CIA notified the Department of State and at 8:30 pm EDT National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy elected to wait until morning to tell the President. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was briefed at midnight. The next morning, Bundy met with Kennedy and showed him the U-2 photographs and briefed him on the CIA’s analysis of the images.[20] At 6:30 pm EDT Kennedy convened a meeting of the nine members of the National Security Council and five other key advisers[21] in a group he formally named the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM) after the fact on October 22 by National Security Action Memorandum 196.[22]

[edit]Responses considered

The U.S. had no plan in place because U.S. intelligence had been convinced that the Soviets would never install nuclear missiles in Cuba. The EXCOMM quickly discussed several possible courses of action, including:[12][23]

- No action.

- Diplomacy: Use diplomatic pressure to get the Soviet Union to remove the missiles.

- Warning: Send a message to Castro to warn him of the grave danger he, and Cuba were in.

- Blockade: Use the U.S. Navy to block any missiles from arriving in Cuba.

- Air strike: Use the U.S. Air Force to attack all known missile sites.

- Invasion: Full force invasion of Cuba and overthrow of Castro.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously agreed that a full-scale attack and invasion was the only solution. They believed that the Soviets would not attempt to stop the U.S. from conquering Cuba. Kennedy was skeptical.

They, no more than we, can not let these things go by without doing something. They can’t, after all their statements, permit us to take out their missiles, kill a lot of Russians, and then do nothing. If they don’t take action in Cuba, they certainly will in Berlin.[24]

Kennedy concluded that attacking Cuba by air would signal the Soviets to presume “a clear line” to conquer Berlin. Kennedy also believed that United States’ allies would think of the U.S. as “trigger-happy cowboys” who lost Berlin because they could not peacefully resolve the Cuban situation.[25]:332

President Kennedy and Secretary of Defense McNamara in an EXCOMM meeting.

The EXCOMM then discussed the effect on the strategic balance of power, both political and military. The Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that the missiles would seriously alter the military balance, but Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara disagreed. He was convinced that the missiles would not affect the strategic balance at all. An extra forty, he reasoned, would make little difference to the overall strategic balance. The U.S. already had approximately 5,000 strategic warheads,[26]:261 while the Soviet Union had only 300. He concluded that the Soviets having 340 would not therefore substantially alter the strategic balance. In 1990, he reiterated that “it made nodifference…The military balance wasn’t changed. I didn’t believe it then, and I don’t believe it now.”[27]

The EXCOMM agreed that the missiles would affect the political balance. First, Kennedy had explicitly promised the American people less than a month before the crisis that “if Cuba should possess a capacity to carry out offensive actions against the United States…the United States would act.”[28]:674-681 Second, U.S. credibility amongst their allies, and amongst the American people, would be damaged if they allowed the Soviet Union to appear to redress the strategic balance by placing missiles in Cuba. Kennedy explained after the crisis that “it would have politically changed the balance of power. It would have appeared to, and appearances contribute to reality.”[29]

President Kennedy meets with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko in the Oval Office (October 18, 1962)

On October 18, President Kennedy met with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Gromyko, who claimed the weapons were for defensive purposes only. Not wanting to expose what he already knew, and wanting to avoid panicking the American public,[30] the President did not reveal that he was already aware of the missile build-up.[31]

By October 19, frequent U-2 spy flights showed four operational sites. As part of the blockade, the U.S. military was put on high alert to enforce the blockade and to be ready to invade Cuba at a moment’s notice. The 1st Armored Division was sent to Georgia, and five army divisions were alerted for maximal action. The Strategic Air Command (SAC) distributed its shorter-ranged B-47 Stratojet medium bombers to civilian airports and sent aloft its B-52 Stratofortress heavy bombers.[32]

[edit]Operational Plans

Two Operational Plans (OPLAN) were considered. OPLAN 316 envisioned a full invasion of Cuba by Army and Marine units supported by the Navy following Air Force and naval airstrikes. However, Army units in the United States would have had trouble fielding mechanized and logistical assets, while the U.S. Navy could not supply sufficient amphibious shipping to transport even a modest armored contingent from the Army. OPLAN 312, primarily an Air Force and Navy carrier operation, was designed with enough flexibility to do anything from engaging individual missile sites to providing air support for OPLAN 316’s ground forces.[33]

[edit]Quarantine

|

|

Kennedy addressing the nation on October 22, 1962 about the buildup of arms on Cuba

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. |

A U.S. Navy P-2H Neptune of VP-18 flying over a Soviet cargo ship with crated Il-28s on deck during the Cuban Crisis.[34]

Kennedy met with members of EXCOMM and other top advisers throughout October 21, considering two remaining options: an air strike primarily against the Cuban missile bases, or a naval blockade of Cuba.[31] A full-scale invasion was not the administration’s first option, but something had to be done. Robert McNamara supported the naval blockade as a strong but limited military action that left the U.S. in control. According to international law a blockade is an act of war, but the Kennedy administration did not think that the USSR would be provoked to attack by a mere blockade.[35]

Admiral Anderson, Chief of Naval Operations wrote a position paper that helped Kennedy to differentiate between a quarantine of offensive weapons and a blockade of all materials, indicating that a classic blockade was not the original intention. Since it would take place in international waters, Kennedy obtained the approval of the OAS for military action under the hemispheric defense provisions of the Rio Treaty.

Latin American participation in the quarantine now involved two Argentine destroyers which were to report to the U.S. Commander South Atlantic [COMSOLANT] at Trinidad on November 9. An Argentine submarine and a Marine battalion with lift were available if required. In addition, two Venezuelan destroyers and one submarine had reported to COMSOLANT, ready for sea by November 2. The Government of Trinidad and Tobago offered the use of Chaguaramas Naval Base to warships of any OAS nation for the duration of the quarantine. The Dominican Republic had made available one escort ship. Colombia was reported ready to furnish units and had sent military officers to the U.S. to discuss this assistance. The Argentine Air Force informally offered three SA-16 aircraft in addition to forces already committed to the quarantine operation.[36]

This initially was to involve a naval blockade against offensive weapons within the framework of the Organization of American States and the Rio Treaty. Such a blockade might be expanded to cover all types of goods and air transport. The action was to be backed up by surveillance of Cuba. The CNO’s scenario was followed closely in later implementing the quarantine.

On October 19, the EXCOMM formed separate working groups to examine the air strike and blockade options, and by the afternoon most support in the EXCOMM shifted to the blockade option.

President Kennedy signs the Proclamation for Interdiction of the Delivery of Offensive Weapons to Cuba at the Oval Office on October 23, 1962.

At 3:00 pm EDT on October 22, President Kennedy formally established the Executive Committee (EXCOMM) with National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 196. At 5:00 pm, he met with Congressional leaders who contentiously opposed a blockade and demanded a stronger response. In Moscow, Ambassador Kohler briefed Chairman Khrushchev on the pending blockade and Kennedy’s speech to the nation. Ambassadors around the world gave advance notice to non-Eastern Bloc leaders. Before the speech, U.S. delegations met with Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and French President Charles de Gaulle to brief them on the U.S. intelligence and their proposed response. All were supportive of the U.S. position.[37]

On October 22 at 7:00 pm EDT, President Kennedy delivered a nation-wide televised address on all of the major networks announcing the discovery of the missiles.

It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.[38]

Kennedy described the administration’s plan:

To halt this offensive buildup, a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba, from whatever nation or port, will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back. This quarantine will be extended, if needed, to other types of cargo and carriers. We are not at this time, however, denying the necessities of life as the Soviets attempted to do in their Berlin blockade of 1948.[38]

During the speech a directive went out to all U.S. forces worldwide placing them on DEFCON 3. The heavy cruiser USS Newport News (CA-148) was designated flagship for the quarantine, with the USS Leary (DD-879) as Newport News’ destroyer escort.[39]

[edit]Crisis deepens

Khrushchev’s October 24, 1962 letter to President Kennedy stating that the Cuban Missile Crisis quarantine “constitute[s] an act of aggression…”

On October 23 at 11:24 am EDT a cable drafted by George Ball to the U.S. Ambassador in Turkey and the U.S. Ambassador toNATO notified them that they were considering making an offer to withdraw what the U.S knew to be nearly obsolete missiles from Italy and Turkey in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal from Cuba. Turkish officials replied that they would “deeply resent” any trade for the U.S. missile’s presence in their country.[40] Two days later, on the morning of October 25, journalist Walter Lippmann proposed the same thing in his syndicated column. Castro reaffirmed Cuba’s right to self-defense and said that all of its weapons were defensive and Cuba will not allow an inspection.[5]

[edit]International response

Kennedy’s speech was not well liked in Britain. The day after the speech, the British press, recalling previous CIA missteps, was unconvinced about the existence of Soviet bases in Cuba, and guessed that Kennedy’s actions might be related to his re-election.[41]

Three days after Kennedy’s speech, the Chinese People’s Daily announced that “650,000,000 Chinese men and women were standing by the Cuban people”.[37]

In Germany, newspapers supported the United States’ response, contrasting it with the weak-kneed American actions in the region during the preceding months. They also expressed some fear that the Soviets might retaliate in Berlin.[41] In France on October 23, the crisis made the front page of all the daily newspapers. The next day, an editorial in Le Monde expressed doubt about the authenticity of the CIA’s photographic evidence. Two days later, after a visit by a high-ranking CIA agent, they accepted the validity of the photographs. Also in France, in the October 29 issue of Le Figaro, Raymond Aron wrote in support of the American response.[41]

[edit]Soviet broadcast

At the time, the crisis continued unabated, and on the evening of October 24, the Soviet news agency Telegrafnoe Agentstvo Sovetskogo Soyuza (TASS) broadcast a telegram from Khrushchev to President Kennedy, in which Khrushchev warned that the United States’ “pirate action” would lead to war. However, this was followed at 9:24 pm by a telegram from Khrushchev to Kennedy which was received at 10:52 pm EDT, in which Khrushchev stated, “If you coolly weigh the situation which has developed, not giving way to passions, you will understand that the Soviet Union cannot fail to reject the arbitrary demands of the United States,” and that the Soviet Union views the blockade as “an act of aggression” and their ships will be instructed to ignore it.

[edit]U.S. alert level raised

Adlai Stevenson shows aerial photos of Cuban missiles to the United Nations. (October 25, 1962)

The United States requested an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council on October 25. In a loud, demanding tone, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Adlai Stevenson confronted Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin in an emergency meeting of the SC challenging him to admit the existence of the missiles. Ambassador Zorin refused to answer. The next day at 10:00 pm EDT, the U.S. raised the readiness level of SAC forces to DEFCON 2. For the only confirmed time in U.S. history, the B-52bombers were dispersed to various locations and made ready to take off, fully equipped, on 15 minutes notice.[42] One-eighth of SAC’s 1,436 bombers were on airborne alert, some 145 intercontinental ballistic missiles stood on ready alert, while Air Defense Command (ADC) redeployed 161 nuclear-armed interceptors to 16 dispersal fields within nine hours with one-third maintaining 15-minute alert status.[33]

“By October 22, Tactical Air Command (TAC) had 511 fighters plus supporting tankers and reconnaissance aircraft deployed to face Cuba on one-hour alert status. However, TAC and the Military Air Transport Service had problems. The concentration of aircraft in Florida strained command and support echelons; we faced critical undermanning in security, armaments, and communications; the absence of initial authorization for war-reserve stocks of conventional munitions forced TAC to scrounge; and the lack of airlift assets to support a major airborne drop necessitated the call-up of 24 Reserve squadrons.”[33]

On October 25 at 1:45 am EDT, Kennedy responded to Khrushchev’s telegram, stating that the U.S. was forced into action after receiving repeated assurances that no offensive missiles were being placed in Cuba, and that when these assurances proved to be false, the deployment “required the responses I have announced… I hope that your government will take necessary action to permit a restoration of the earlier situation.”

A recently declassified map used by the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Fleet showing the position of American and Soviet ships at the height of the crisis.

[edit]Quarantine challenged

At 7:15 am EDT on October 25, the USS Essex and USS Gearing attempted to intercept the Bucharest but failed to do so. Fairly certain the tanker did not contain any military material, they allowed it through the blockade. Later that day, at 5:43 pm, the commander of the blockade effort ordered the USS Kennedy to intercept and board the Lebanese freighter Marucla. This took place the next day, and the Marucla was cleared through the blockade after its cargo was checked.[43]

At 5:00 pm EDT on October 25, William Clements announced that the missiles in Cuba were still actively being worked on. This report was later verified by a CIA report that suggested there had been no slow-down at all. In response, Kennedy issued Security Action Memorandum 199, authorizing the loading of nuclear weapons onto aircraft under the command of SACEUR (which had the duty of carrying out first air strikes on the Soviet Union). During the day, the Soviets responded to the quarantine by turning back 14 ships presumably carrying offensive weapons.[42]

[edit]Crisis stalemated

The next morning, October 26, Kennedy informed the EXCOMM that he believed only an invasion would remove the missiles from Cuba. However, he was persuaded to give the matter time and continue with both military and diplomatic pressure. He agreed and ordered the low-level flights over the island to be increased from two per day to once every two hours. He also ordered a crash program to institute a new civil government in Cuba if an invasion went ahead.

At this point, the crisis was ostensibly at a stalemate. The USSR had shown no indication that they would back down and had made several comments to the contrary. The U.S. had no reason to believe otherwise and was in the early stages of preparing for an invasion, along with a nuclear strike on the Soviet Union in case it responded militarily, which was assumed.[44]

[edit]Secret negotiations

At 1:00 pm EDT on October 26, John A. Scali of ABC News had lunch with Aleksandr Fomin at Fomin’s request. Fomin noted, “War seems about to break out,” and asked Scali to use his contacts to talk to his “high-level friends” at the State Department to see if the U.S. would be interested in a diplomatic solution. He suggested that the language of the deal would contain an assurance from the Soviet Union to remove the weapons under UN supervision and that Castro would publicly announce that he would not accept such weapons in the future, in exchange for a public statement by the U.S. that it would never invade Cuba.[45]The U.S. responded by asking the Brazilian government to pass a message to Castro that the U.S. would be “unlikely to invade” if the missiles were removed.[40]

Mr. President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our countries dispose.

Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.

Letter From Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy, October 26, 1962

[46]

On October 26 at 6:00 pm EDT, the State Department started receiving a message that appeared to be written personally by Khrushchev. It was Saturday at 2:00 am in Moscow. The long letter took several minutes to arrive, and it took translators additional time to translate and transcribe the long letter.[40]

Robert Kennedy described the letter as “very long and emotional.” Khrushchev reiterated the basic outline that had been stated to John Scali earlier in the day, “I propose: we, for our part, will declare that our ships bound for Cuba are not carrying any armaments. You will declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its troops and will not support any other forces which might intend to invade Cuba. Then the necessity of the presence of our military specialists in Cuba will disappear.” At 6:45 pm EDT, news of Fomin’s offer to Scali was finally heard and was interpreted as a “set up” for the arrival of Khrushchev’s letter. The letter was then considered official and accurate, although it was later learned that Fomin was almost certainly operating of his own accord without official backing. Additional study of the letter was ordered and continued into the night.[40]

[edit]Crisis continues

Direct aggression against Cuba would mean nuclear war. The Americans speak about such aggression as if they did not know or did not want to accept this fact. I have no doubt they would lose such a war. —Ernesto “Che” Guevara, October 1962[47]

S-75 Dvina with V-750V 1D missile on a launcher. An installation similar to this one shot down Major Anderson’s U-2 over Cuba.

Castro, on the other hand, was convinced that an invasion was soon at hand, and he dictated a letter to Khrushchev that appeared to call for a preemptive strike on the U.S. However, in a 2010 interview, Castro said of his recommendation for the Soviets to bomb America “After I’ve seen what I’ve seen, and knowing what I know now, it wasn’t worth it at all.”[48] Castro also ordered all anti-aircraft weapons in Cuba to fire on any U.S. aircraft,[49] whereas in the past they had been ordered only to fire on groups of two or more. At 6:00 am EDT on October 27, the CIA delivered a memo reporting that three of the four missile sites at San Cristobal and the two sites at Sagua la Grande appeared to be fully operational. They also noted that the Cuban military continued to organize for action, although they were under order not to initiate action unless attacked.[citation needed]

At 9:00 am EDT on October 27, Radio Moscow began broadcasting a message from Khrushchev. Contrary to the letter of the night before, the message offered a new trade, that the missiles on Cuba would be removed in exchange for the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey. At 10:00 am EDT, the executive committee met again to discuss the situation and came to the conclusion that the change in the message was due to internal debate between Khrushchev and other party officials in the Kremlin.[50]:300 McNamara noted that another tanker, the Grozny, was about 600 miles (970 km) out and should be intercepted. He also noted that they had not made the USSR aware of the quarantine line and suggested relaying this information to them via U Thant at the United Nations.

A Lockheed U-2F, the high altitude reconnaissance type shot down over Cuba, being refueled by a Boeing KC-135Q. The aircraft in 1962 was painted overall gray and carried USAF military markings and national insignia.

While the meeting progressed, at 11:03 am EDT a new message began to arrive from Khrushchev. The message stated, in part,

You are disturbed over Cuba. You say that this disturbs you because it is ninety-nine miles by sea from the coast of the United States of America. But… you have placed destructive missile weapons, which you call offensive, in Italy and Turkey, literally next to us… I therefore make this proposal: We are willing to remove from Cuba the means which you regard as offensive… Your representatives will make a declaration to the effect that the United States … will remove its analogous means from Turkey … and after that, persons entrusted by the United Nations Security Council could inspect on the spot the fulfillment of the pledges made.

The executive committee continued to meet through the day.

Throughout the crisis, Turkey had repeatedly stated that it would be upset if the Jupiter missiles were removed. Italy’s Prime Minister Fanfani, who was also Foreign Minister ad interim, offered to allow withdrawal of the missiles deployed in Apulia as a bargaining chip. He gave the message to one of his most trusted friends, Ettore Bernabei, the general manager of RAI-TV, to convey to Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.. Bernabei was in New York to attend an international conference on satellite TV broadcasting. Unknown to the Soviets, the U.S regarded the Jupiter missiles as obsolete and already supplanted by the Polaris nuclear ballistic submarine missiles.[9]

On the morning of October 27, a U-2F (the third CIA U-2A, modified for air-to-air refueling) piloted by USAF Major Rudolf Anderson,[51] departed its forward operating location at McCoy AFB, Florida, and at approximately 12:00 pm EDT, the aircraft was struck by a S-75 Dvina (NATOdesignation SA-2 Guideline) SAM missile launched from Cuba. The aircraft was shot down and Anderson was killed. The stress in negotiations between the USSR and the U.S. intensified, and only much later was it learned that the decision to fire the missile was made locally by an undetermined Soviet commander acting on his own authority. Later that day, at about 3:41 pm EDT, several U.S. Navy RF-8A Crusader aircraft on low-level photoreconnaissance missions were fired upon, and one was hit by a 37 mm shell but managed to return to base.

At 4:00 pm EDT, Kennedy recalled members of EXCOMM to the White House and ordered that a message immediately be sent to U Thant asking the Soviets to “suspend” work on the missiles while negotiations were carried out. During this meeting, Maxwell Taylor delivered the news that the U-2 had been shot down. Kennedy had earlier claimed he would order an attack on such sites if fired upon, but he decided to not act unless another attack was made. In an interview 40 years later, McNamara said:

We had to send a U-2 over to gain reconnaissance information on whether the Soviet missiles were becoming operational. We believed that if the U-2 was shot down that—the Cubans didn’t have capabilities to shoot it down, the Soviets did—we believed if it was shot down, it would be shot down by a Soviet surface-to-air-missile unit, and that it would represent a decision by the Soviets to escalate the conflict. And therefore, before we sent the U-2 out, we agreed that if it was shot down we wouldn’t meet, we’d simply attack. It was shot down on Friday […]. Fortunately, we changed our mind, we thought “Well, it might have been an accident, we won’t attack.” Later we learned that Khrushchev had reasoned just as we did: we send over the U-2, if it was shot down, he reasoned we would believe it was an intentional escalation. And therefore, he issued orders to Pliyev, the Soviet commander in Cuba, to instruct all of his batteries not to shoot down the U-2.[note 1][52]

[edit]Drafting the response

Emissaries sent by both Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev agreed to meet at the Yenching Palace Chinese restaurant in the Cleveland Park neighborhood of Washington D.C. on the evening of October 27.[53]Kennedy suggested that they take Khrushchev’s offer to trade away the missiles. Unknown to most members of the EXCOMM, Robert Kennedy had been meeting with the Soviet Ambassador in Washington to discover whether these intentions were genuine. The EXCOMM was generally against the proposal because it would undermine NATO‘s authority, and the Turkish government had repeatedly stated it was against any such trade.

As the meeting progressed, a new plan emerged and Kennedy was slowly persuaded. The new plan called for the President to ignore the latest message and instead to return to Khrushchev’s earlier one. Kennedy was initially hesitant, feeling that Khrushchev would no longer accept the deal because a new one had been offered, but Llewellyn Thompson argued that he might accept it anyway. White House Special Counsel and Adviser Ted Sorensen and Robert Kennedy left the meeting and returned 45 minutes later with a draft letter to this effect. The President made several changes, had it typed, and sent it.

After the EXCOMM meeting, a smaller meeting continued in the Oval Office. The group argued that the letter should be underscored with an oral message to Ambassador Dobrynin stating that if the missiles were not withdrawn, military action would be used to remove them. Dean Rusk added one proviso, that no part of the language of the deal would mention Turkey, but there would be an understanding that the missiles would be removed “voluntarily” in the immediate aftermath. The President agreed, and the message was sent.

An EXCOMM meeting on October 29, 1962 held in the White House Cabinet Room during the Cuban Missile Crisis. President Kennedy is to the left of the American flag; on his left is Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and his right is Secretary of StateDean Rusk.

At Juan Brito’s request, Fomin and Scali met again. Scali asked why the two letters from Khrushchev were so different, and Fomin claimed it was because of “poor communications”. Scali replied that the claim was not credible and shouted that he thought it was a “stinking double cross”. He went on to claim that an invasion was only hours away, at which point Fomin stated that a response to the U.S. message was expected from Khrushchev shortly, and he urged Scali to tell the State Department that no treachery was intended. Scali said that he did not think anyone would believe him, but he agreed to deliver the message. The two went their separate ways, and Scali immediately typed out a memo for the EXCOMM.[citation needed]

Within the U.S. establishment, it was well understood that ignoring the second offer and returning to the first put Khrushchev in a terrible position. Military preparations continued, and all active duty Air Force personnel were recalled to their bases for possible action. Robert Kennedy later recalled the mood, “We had not abandoned all hope, but what hope there was now rested with Khrushchev’s revising his course within the next few hours. It was a hope, not an expectation. The expectation was military confrontation by Tuesday, and possibly tomorrow…”[citation needed]

At 8:05 pm EDT, the letter drafted earlier in the day was delivered. The message read, “As I read your letter, the key elements of your proposals—which seem generally acceptable as I understand them—are as follows: 1) You would agree to remove these weapons systems from Cuba under appropriate United Nations observation and supervision; and undertake, with suitable safe-guards, to halt the further introduction of such weapon systems into Cuba. 2) We, on our part, would agree—upon the establishment of adequate arrangements through the United Nations, to ensure the carrying out and continuation of these commitments (a) to remove promptly the quarantine measures now in effect and (b) to give assurances against the invasion of Cuba.” The letter was also released directly to the press to ensure it could not be “delayed.”[citation needed]

With the letter delivered, a deal was on the table. However, as Robert Kennedy noted, there was little expectation it would be accepted. At 9:00 pm EDT, the EXCOMM met again to review the actions for the following day. Plans were drawn up for air strikes on the missile sites as well as other economic targets, notably petroleum storage. McNamara stated that they had to “have two things ready: a government for Cuba, because we’re going to need one; and secondly, plans for how to respond to the Soviet Union in Europe, because sure as hell they’re going to do something there”.[citation needed]

At 12:12 am EDT, on October 27, the U.S. informed its NATO allies that “the situation is growing shorter… the United States may find it necessary within a very short time in its interest and that of its fellow nations in the Western Hemisphere to take whatever military action may be necessary.” To add to the concern, at 6 am the CIA reported that all missiles in Cuba were ready for action.

Later on that same day, what the White House later called “Black Saturday,” the U.S. Navy dropped a series of “signaling depth charges” (practice depth charges the size of hand grenades[54]) on a Soviet submarine (B-59) at the quarantine line, unaware that it was armed with a nuclear-tipped torpedo with orders that allowed it to be used if the submarine was “holed” (a hole in the hull from depth charges or surface fire).[55] On the same day, a U.S. U-2 spy plane made an accidental, unauthorized ninety-minute overflight of the Soviet Union’s far eastern coast.[56] The Soviets scrambled MiG fighters from Wrangel Island and in response the American sent aloft F-102 fighters armed with nuclear air-to-air missiles over the Bering Sea.[57]

[edit]Crisis ends

After much deliberation between the Soviet Union and Kennedy’s cabinet, Kennedy secretly agreed to remove all missiles set in southern Italy and in Turkey, the latter on the border of the Soviet Union, in exchange for Khrushchev removing all missiles in Cuba.

At 9:00 am EDT, on October 28, a new message from Khrushchev was broadcast on Radio Moscow. Khrushchev stated that, “the Soviet government, in addition to previously issued instructions on the cessation of further work at the building sites for the weapons, has issued a new order on the dismantling of the weapons which you describe as ‘offensive’ and their crating and return to the Soviet Union.”

Kennedy immediately responded, issuing a statement calling the letter “an important and constructive contribution to peace”. He continued this with a formal letter: “I consider my letter to you of October twenty-seventh and your reply of today as firm undertakings on the part of both our governments which should be promptly carried out… The U.S. will make a statement in the framework of the Security Council in reference to Cuba as follows: it will declare that the United States of America will respect the inviolability of Cuban borders, its sovereignty, that it take the pledge not to interfere in internal affairs, not to intrude themselves and not to permit our territory to be used as a bridgehead for the invasion of Cuba, and will restrain those who would plan to carry an aggression against Cuba, either from U.S. territory or from the territory of other countries neighboring to Cuba.”[58]:103

The U.S continued the quarantine, and in the following days, aerial reconnaissance proved that the Soviets were making progress in removing the missile systems. The 42 missiles and their support equipment were loaded onto eight Soviet ships. The ships left Cuba from November 5–9. The U.S. made a final visual check as each of the ships passed the quarantine line. Further diplomatic efforts were required to remove the Soviet IL-28 bombers, and they were loaded on three Soviet ships on December 5 and 6. Concurrent with the Soviet commitment on the IL-28’s, the U.S. Government announced the end of the quarantine effective at 6:45 pm EDT on November 20, 1962.[32]

In his negotiations with the Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy informally proposed that the Jupiter missiles in Turkey would be removed “within a short time after this crisis was over.”[59]:222 The last U.S. missiles were disassembled by April 24, 1963, and were flown out of Turkey soon after.[60]

The practical effect of this Kennedy-Khrushchev Pact was that it effectively strengthened Castro’s position in Cuba, guaranteeing that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. It is possible that Khrushchev only placed the missiles in Cuba to get Kennedy to remove the missiles from Italy and Turkey and that the Soviets had no intention of resorting to nuclear war if they were out-gunned by the Americans.[61] Because the withdrawal of the Jupiter missiles from NATO bases in Southern Italy and Turkey was not made public at the time, Khrushchev appeared to have lost the conflict and become weakened. The perception was that Kennedy had won the contest between the superpowers and Khrushchev had been humiliated. This is not entirely the case as both Kennedy and Khrushchev took every step to avoid full conflict despite the pressures of their governments. Khrushchev held power for another two years.[58]:102-105

[edit]Aftermath

The Jupiter intermediate-range ballistic missile. The U.S. secretly agreed to withdraw these missiles from Italy and Turkey.

Ibrahim-2 Jupiter Missile in Turkey.

The compromise was a particularly sharp embarrassment for Khrushchev and the Soviet Union because the withdrawal of U.S. missiles from Italy and Turkey was not made public—it was a secret deal between Kennedy and Khrushchev. The Soviets were seen as retreating from circumstances that they had started—though if played well, it could have looked just the opposite. Khrushchev’s fall from power two years later can be partially linked to Politburo embarrassment at both Khrushchev’s eventual concessions to the U.S. and his ineptitude in precipitating the crisis in the first place.

Cuba perceived it as a partial betrayal by the Soviets, given that decisions on how to resolve the crisis had been made exclusively by Kennedy and Khrushchev. Castro was especially upset that certain issues of interest to Cuba, such as the status of Guantanamo, were not addressed. This caused Cuban-Soviet relations to deteriorate for years to come.[62]:278 On the other hand, Cuba continued to be protected from invasion.

One U.S. military commander was not happy with the result either. General LeMay told the President that it was “the greatest defeat in our history” and that the U.S. should have immediately invaded Cuba.

The Cuban Missile Crisis spurred the Hotline Agreement, which created the Moscow–Washington hotline, a direct communications link between Moscow and Washington, D.C. The purpose was to have a way that the leaders of the two Cold War countries could communicate directly to solve such a crisis. The world-wide U.S. Forces DEFCON 3 status was returned to DEFCON 4 on November 20, 1962. U-2 pilot Major Anderson’s body was returned to the United States and he was buried with full military honors in South Carolina. He was the first recipient of the newly-created Air Force Cross, which was awarded posthumously.

Although Anderson was the only combat fatality during the crisis, eleven crew members of three reconnaissance Boeing RB-47 Stratojets of the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing were also killed in crashes during the period between September 27 and November 11, 1962.[63]

Critics including Seymour Melman[64] and Seymour Hersh[65] suggested that the Cuban Missile Crisis encouraged U.S. use of military means, such as in the Vietnam War. This Soviet-American confrontation was synchronous with the Sino-Indian War, dating from the U.S.’s military quarantine of Cuba; historians[who?] speculate that the Chinese attack against India for disputed land was meant to coincide with the Cuban Missile Crisis.[66]

[edit]Post-crisis history

A U.S. Navy HSS-1 Seabat helicopter hovers over Soviet submarine B-59, forced to the surface by U.S. Naval forces in the Caribbean near Cuba (October 28–29, 1962)

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., a historian and adviser to John F. Kennedy, told National Public Radio in an interview on October 16, 2002 that Castro did not want the missiles, but that Khrushchev had pressured Castro to accept them. Castro was not completely happy with the idea but the Cuban National Directorate of the Revolution accepted them to protect Cuba against U.S. attack, and to aid its ally, the Soviet Union.[62]:272 Schlesinger believed that when the missiles were withdrawn, Castro was angrier with Khrushchev than he was with Kennedy because Khrushchev had not consulted Castro before deciding to remove them.[note 2]

In early 1992, it was confirmed that Soviet forces in Cuba had, by the time the crisis broke, received tactical nuclear warheads for their artillery rockets and Il-28 bombers.[67] Castro stated that he would have recommended their use if the U.S. invaded despite knowing Cuba would be destroyed.[67]

Arguably the most dangerous moment in the crisis was only recognized during the Cuban Missile Crisis Havana conference in October 2002. Attended by many of the veterans of the crisis, they all learned that on October 26, 1962 the USS Beale had tracked and dropped signaling depth charges (the size of hand grenades) on the B-59, a Soviet Project 641 (NATO designation Foxtrot) submarine which, unknown to the U.S., was armed with a 15 kiloton nuclear torpedo. Running out of air, the Soviet submarine was surrounded by American warships and desperately needed to surface. An argument broke out among three officers on the B-59, including submarine captain Valentin Savitsky, political officer Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov, and Deputy brigade commander Captain 2nd rank (US Navy Commander rank equivalent) Vasili Arkhipov. An exhausted Savitsky became furious and ordered that the nuclear torpedo on board be made combat ready. Accounts differ about whether Commander Arkhipov convinced Savitsky not to make the attack, or whether Savitsky himself finally concluded that the only reasonable choice left open to him was to come to the surface.[68]:303, 317 During the conference Robert McNamara stated that nuclear war had come much closer than people had thought. Thomas Blanton, director of the National Security Archive, said, “A guy called Vasili Arkhipov saved the world.”

The crisis was a substantial focus of the 2003 documentary, The Fog of War, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.