The FBI reorts –

|

|

|---|---|

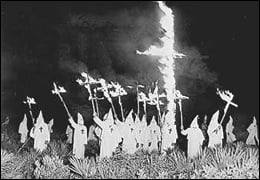

| Early KKK rally in Florida. Photo courtesy of the National Archives. |

Ninety-five years ago this month—in February 1915—the D.W. Griffith movie later titled The Birth of a Nation premiered in a Los Angeles theater. Though considered progressive in its technique and style, the film had a decidedly backwards plot that glorified a short-lived, post-Civil War white supremacist group called the Ku Klux Klan. The movie’s broad release in March provoked riots and even bloodshed nationwide.

It also revived interest in the KKK, leading to the birth of several new local groups that summer and fall. Many more followed, mostly in southern states at first. Some of these groups focused on supporting the U.S. effort in World War I, but most wallowed in a toxic mix of secrecy, racism, and violence.

As the Klan grew, it attracted the attention of the young Bureau. Created just a few years earlier—in July 1908—the Bureau of Investigation (as the organization was known then) had few federal laws to combat the KKK in these formative days. Cross burnings and lynchings, for example, were local issues. But under its general domestic security responsibilities, the Bureau was able to start gathering information and intelligence on the Klan and its activities. And wherever possible, we looked for federal violations and shared information with state and local law enforcement for its cases.

Our early files show that Bureau cases and intelligence efforts were already beginning to mount in the years before 1920. A few examples:

- In Birmingham, a middle-aged African-American—who fled north to avoid serving in the war—was arrested for draft dodging in May 1918 when he returned to persuade his white teenage girlfriend to marry him. A Bureau agent looking into the matter discovered that the local KKK had gotten wind of the interracial affair and was organizing to lynch the man. The agent came up with a novel solution to resolve the draft-dodging issue and to protect the man from harm: he escorted the evader to a military camp and ensured that he was quickly inducted.

- In June 1918, a Mobile agent named G.C. Outlaw learned that Ed Rhone—the leader of a multi-racial group called the Knights of Labor—was worried by the abduction of another labor leader by reputed Klansmen. “This uneasiness of the Knights of Labor,” our agent noted, “is the first direct result of the Ku Klux activities.” Agent Outlaw investigated and assured Rhone we would protect him from any possible harm.

- At the request of a Bureau agent in Tampa, a representative of the American Protective League—a group of citizen volunteers who helped investigate domestic issues like draft evasion during World War I—convinced an area Klan group to disband in August 1918.

World War I effectively came to an end with the signing of a ceasefire in November 1918, but the KKK was just getting started. Pro-war oriented Klan groups either folded or began to coalesce around a focus on racial and religious prejudice. Teaming up with advertising executive Edward Young Clarke, the head of the Atlanta Klan—William Simmons—would oversee a rapid rise in KKK membership in the 1920s.

That’s another story, and one that we will tell as part of this new history series detailing the work of the FBI to protect the American people—especially minorities and other groups—from the evils of the modern-day Klan. Over the course of the year, we will track the major aspects of this fight, with new documents and pictures to help tell the tale. Stay tuned.